Tuning in to the benefits of music

Photo by Keith Nordstrom

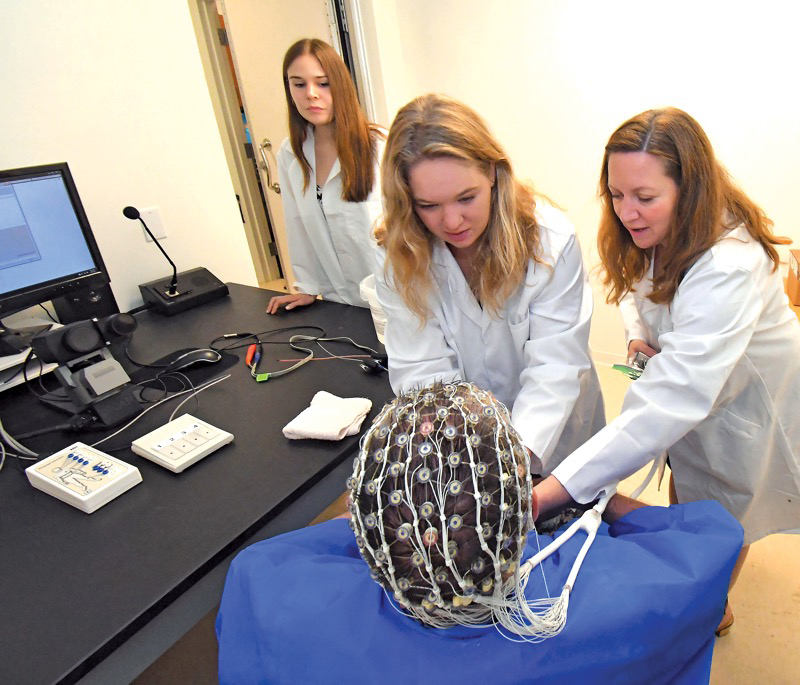

Assistant Professor of Psychology Katherine Eskine, who has been studying older adults with memory problems for 15 years, this past summer began researching the effects of listening to music on cognition. Supported by funding from a Clemence Award, the professor worked with interns Clara Colas ’19, a psychology and Italian studies double major, and Jennifer Elwell ’18, a music and psychology double major (funded by a Wheaton fellowship), to test volunteer participants from several area senior centers, including Norton Senior Center. Editor Sandy Coleman loves music and wanted to know more.

How can we use music to improve our memory?

There are a number of ways music can be used to increase memory: As a way to more effectively store memory; as cues to recall specific events; as a way to increase attention during encoding; and as a way to decrease stress and thereby aid in retrieval. Think of the ABCs. We learned the song and lyrics together, breaking what once was a complex string of letters L M N O P into what cognitive psychologists call a chunk. This works in the same way as trying to remember three random letters like WMB. If we rearrange the numbers into a chunk like BMW it is much easier to remember. Music helps group the parts of the alphabet into easier-to-remember sections or phrases.

The second way music can help with memory is to cue a specific event. Listening to your high school class song might elicit memories of high school. Listening to your favorite album from your teenage years might flood your mind with memories of friends, parties and places you thought you had long forgotten. When we are studying information for a test or quiz, music can increase attention and decrease stress; both can have an effect on memory. However, listening to music with words when you are reading or music that you know how to play on an instrument can compete for attention with the information you are attempting to remember. So if you do listen to music while you work, aim for music without lyrics or music that you do not know how to play.

Describe the testing.

Each volunteer is tested twice, once with babble and once with music. Babble sounds, like people talking at a party, are used as a control for music. Volunteers are given a number of tests that measure cognitive abilities like processing speed, short-term memory, long-term memory and executive function. These tests are given before and after music listening and babble. We have alternate versions of the tests, and the order is counterbalanced to minimize practice effects. Finally, participants are asked to come back a final time and we record brain wave activation while they are listening to the same music they listened to during the testing phase. This way we can begin to understand the neurological underpinnings of any enhancements on the cognitive measures.

What did you enjoy most about working with your two students?

My lab is a collaborative environment, and Clara and Jenny contributed many excellent ideas about the path of the research. They were also very independent, and it was wonderful to watch them take ownership of the project. College students and 70-year-old community members don’t spend nearly enough time with each other. My favorite part was hearing about the joy that these interactions provided for all involved.

Is this research connected to your teaching?

Very much so. Understanding how music affects and is represented in the brain is an excellent way to learn about the function and organization of the brain. In my “Cognitive Neuroscience” course we have a four-week section on music and the brain. I also talk about this and related research in my “Cognitive Psychology” course.