Overdue recognition

Professor Emerita Hilda Geiringer’s contributions to math recognized in new BBC series

Esteemed Wheaton math professor, the late Hilda Geiringer, recently was recognized for her previously overlooked contributions to the field of mathematics in the first article in a new BBC Future series titled “Missed Genius.”

The series seeks to share the untold stories of individuals from diverse backgrounds who have helped to shape modern understanding of life and the universe, to “celebrate the ‘missed geniuses’ who made the world what it is today,” according to BBC Future.

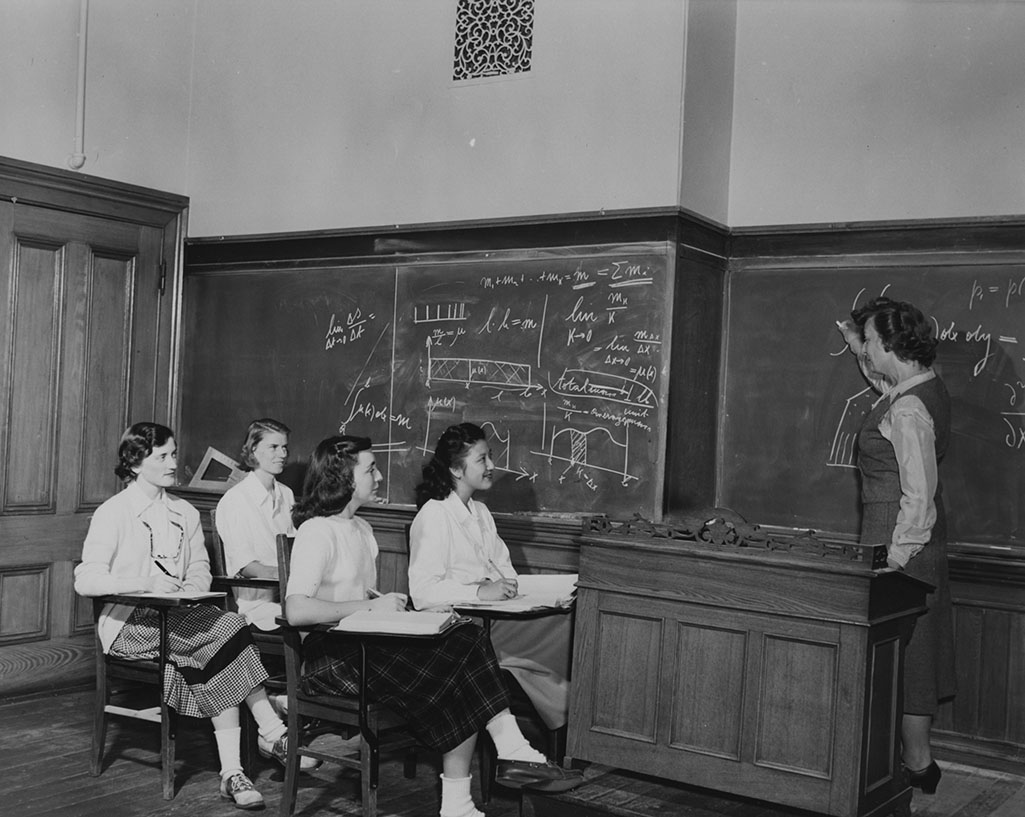

Geiringer, born in Vienna to Jewish parents, was a pioneer in applied mathematics and as a woman in the field. She was the first woman to teach applied mathematics at a German university, and she mentored a large number of Wheaton students in pursuing advanced studies in math during the 1940s and 50s.

Wheaton College has a long history of promoting women in the sciences, beginning with its founding as a women’s seminary in 1834. This spring, the college will host its fourth annual Summit for Women in STEM, which brings together hundreds of students, faculty and other professionals to discuss the challenges and opportunities for women in the STEM fields. Supported by a $1 million grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Wheaton is developing other new initiatives to enhance student engagement and improve learning outcomes in the sciences.

“[S]he was part of an early vanguard in 20th-century applied mathematics at a time when the field was trying to find institutional legitimacy and independence from pure mathematics,” Leila McNeill wrote in the BBC article. “With crucial contributions to mathematical theories of plasticity and to probability genetics, Geiringer helped advance the field of applied mathematics, laying fundamental groundwork which many parts of science and engineering rely upon today.”

But with the growing Nazi threat in Germany, Geiringer wasn’t able to maintain her position at the University of Berlin, forced to leave the country with her young daughter, first to Turkey and eventually to the United States, in 1939. She took an unpaid position at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, where she worked for five years while she searched for a university position. Eventually, in spring 1944, she was hired as a math professor by Wheaton College, under the leadership of President J. Edgar Park, according to Wheaton Archivist Mark Armstrong.

In a letter recommending her for the position, written in February 1944, Park said, “[…] I really think that Mrs. Geiringer would probably become one of the best teachers of the college.”

Geiringer’s tenure at Wheaton was marked by her dedication to Wheaton students and to the advancement of the field of applied mathematics. She taught several advanced courses in mathematics at Wheaton, along with elementary mathematics, which was her favorite course to teach, according to a news release issued from the college upon her retirement. While at Wheaton, she published more than 80 articles, reviews and books on pure and applied mathematics, and, following the death of her husband, mathematician Richard von Mises, in 1953, she assumed his research projects at Harvard University, where he was a professor of applied mathematics and aerodynamics.

“She was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1955—a truly rare honor—and also was a fellow of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics, the American Mathematical Society and other similar (though unnamed in our sources) groups,” Armstrong said.

While at Wheaton, during World War II, Geiringer conducted classified research for the National Defense Research Council.

She retired from Wheaton in 1959, earning the title of professor emerita, and was awarded an honorary doctorate from the college the following year, Armstrong said.

Along with her impact in academics—according to her obituary, published in the Wheaton College Newsletter on April 24, 1973, Geiringer “directed an unusual proportion of mathematics majors in individual research projects in probability and statistics”—she also donated to Wheaton her collection of rare volumes of German literature. One of these gifts, highlighted in a recent article in Wheaton magazine, was a volume of Aristotle printed in Leipzig in 1519, Armstrong noted.