#TBT: Wheaton, McCarthyism and academic freedom

“I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and that I will faithfully discharge the duties of the position of [professor] in [Wheaton College] according to the best of my ability.”

From 1935 to 1967, all teachers and professors at both public and private schools and colleges in Massachusetts had to swear to and sign the above oath if they wanted to keep their jobs. The massive unemployment and subsequent population migrations of the Great Depression led to increased interest in socialism, communism and populist political and economic movements. Loyalty oaths, passed by Massachusetts and many other states, were believed to protect the impressionable minds of students from such radicalism during this “First Red Scare.”

The issue of Loyalty Oaths appeared repeatedly throughout the first half of the 20th century. During World War II and the 1950s, the “Second Red Scare” of McCarthyism emerged. In 1941, Wheaton’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) discussed a petition from several New England colleges to condemn the so-called Rapp-Coudert Committee in New York, which was investigating communist influence in that state’s public education system. The petition criticized the committee’s activities as a “witch hunt” and “public hysteria” meant to “intimidate the scholastic profession or to bring discredit on education in general” but was tabled by the Wheaton faculty without further action.

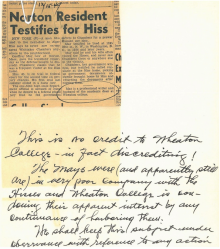

While no one connected with Wheaton was called before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee, Dean of the College Elizabeth Stoffregen May and her husband Geoffrey May attracted public attention during the trials of Alger Hiss in 1949.

The Mays lived next door to, and socialized with, the Hiss family in Washington, D.C. during the 1930s. Although prosecution witness Whittaker Chambers claimed that he frequently met with Hiss in his home to collect secret government documents, Geoffrey May testified for the defense that he had never seen Chambers. When an account of May’s participation in the trial was published in the Attleboro, Mass., paper, at least one critical anonymous letter accused the college of “discrediting” itself by “harboring” the Mays, stating, “We shall keep this subject under observance with reference to any action on your part.” President Alexander Howard Meneely refused Dean May’s offer to resign over the issue.

Again in 1951, the Massachusetts Committee on Education held hearings on House Bill 743, designed to require presidents of colleges and schools “to expel Communists or Communist sympathizers from their teaching staffs under penalty of revocation of [the] institution’s charter.” The state’s Civil Liberties Union asked President Meneely to represent Wheaton at the hearing. Unable to attend, Meneely indicated that, a year earlier, he had made a “full, vigorous statement … asserting the College’s opposition to the bill,” placing “the college on record as unequivocally opposed to it.” Wheaton’s AAUP Committee sent Professor Henrietta Jennings to the hearing to make certain that the college’s opinion was heard.

The Massachusetts bill remained a matter of concern for the remainder of the year. By November, Professor of History Ernest John “Jack” Knapton had taken up the cause. He reported to the AAUP his attempts to meet Massachusetts House Speaker Thomas Philip “Tip” O’Neill “concerning the bill now before the legislature to punish colleges and universities for employing communists or communist sympathizers.” Wheaton’s faculty encouraged Knapton “to continue his activities in opposition to the bill.”

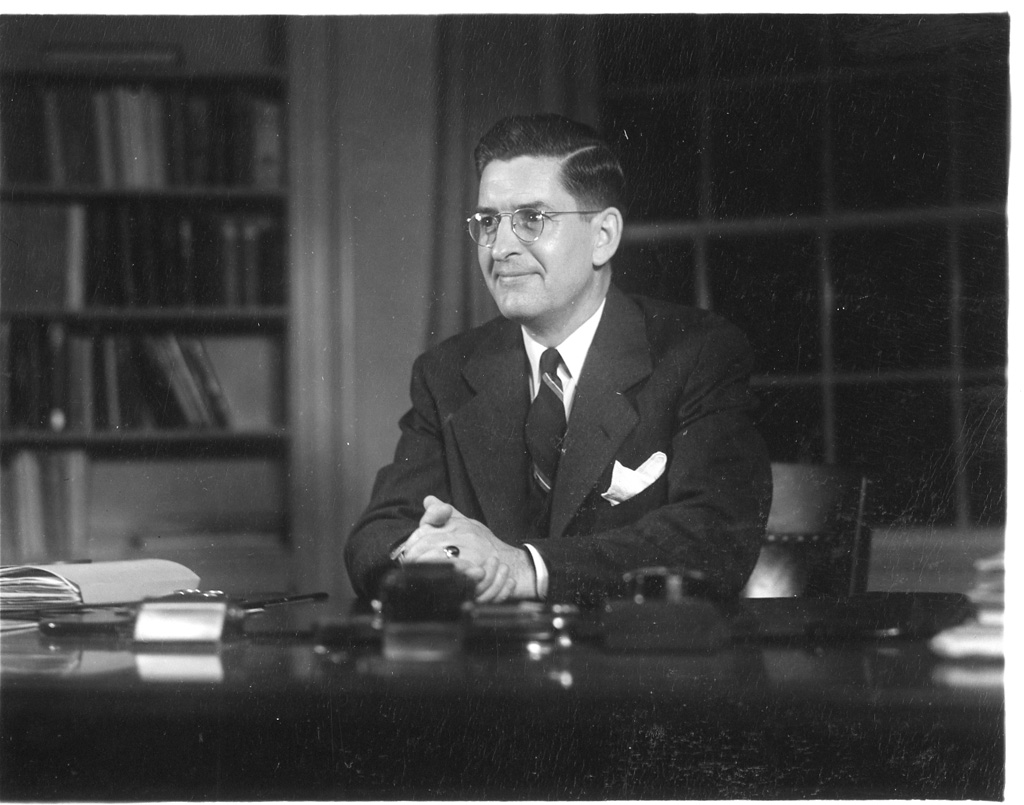

A. Howard Meneely, a Dartmouth History professor before becoming Wheaton’s president in 1944, was a strong advocate for academic freedom, and thus absolutely opposed to the imposition of loyalty oaths. His January 1952 speech to the American Association of University Women in Boston stated his argument.

“I have been much disturbed over what appears to be a tendency to undermine the confidence of our citizens in our colleges and universities by charges of radicalism and subversive teaching,” Meneely said. “This is reminiscent of the hysteria that prevailed in the years after the first world war. Too often legislatures, public officials and even governing boards of educational institutions have imposed oaths or restrictions or penalties of one kind or another upon teachers. If oaths and restraints upon teachers are deemed essential because of their influence in molding youth, why should not similar ‘safeguards’ be applied to members of the press, radio commentators, writers, the makers of comic strips, our clergy, and sundry others, all of whom also exert an important influence in molding the minds of youth?”

Believing that both conformity and repression were equal threats to academic freedom, Meneely put his faith in students, who “are quick to see through fraud and bias” and “are not readily swayed.”

Meneely further refined his position on loyalty when addressing Wheaton’s students in Morning Chapel the following year: “I would not knowingly appoint a Communist to a place on the Wheaton faculty. Nor would I knowingly retain a Communist on our faculty. Communists are not dedicated to seeking or teaching the truth.” But, he continued, “a college like ours should be a place where divergent views should find free and cogent expression. Unusual or unpopular beliefs need to be considered, analyzed and evaluated along with those which find more ready acceptance. … If we have faith and believe in the validity of our own system, we need have not fear about studying a different one, whether it be fascist or communistic.”

As the years passed, faculty members continued to criticize the loyalty oath requirement. Louis H. Leiter, instructor in English in 1957–58, complained bitterly, “I went through five years of World War II without any questions concerning loyalty—grew up in the Army during those years—in contrast this oath seems such a mean little whimper.”

Meneely, constrained by state law, replied, “I myself do not like the requirement and regret that it exists, but I am afraid there is nothing I can do about it.”

The National Defense Education Act of 1958, though applauded for providing funding for scientific initiatives at educational institutions, required a “disclaimer affidavit” against overthrowing the U.S. government. Once again, colleges and universities protested.

President Meneely wrote to Senator James Murray, chairman of the hearings on the offensive section, saying: “I have deplored the requirement of a ‘disclaimer affidavit’ and the requirement of an affirmative vote of allegiance. I believe the overwhelming majority of young people in our colleges are just as loyal as any other citizens, and I deplore the fact that any of them should be subjected to requirements of allegiance simply because they may need financial aid.”

The national chapter of the AAUP sent questionnaires to the local chapters regarding actions to be taken against the provision. While a majority of those who responded wanted to oppose the affidavit, the only action taken was a brief letter to the central chapter supporting repeal of the provision. By the time the disclaimer was repealed in 1962, Wheaton was one of 153 colleges protesting the clause.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court finally invalidated the state teachers’ loyalty oath legislation in 1967. Only in 1986 did the Massachusetts General Court repeal all loyalty oaths.

This article was written by Wheaton College archivist Zephorene Stickney. Images courtesy of the Wheaton Archives and Special Collections.