William Richards ’04 has built a fulfilling career

Author, creative consultant explores meaning and responsibility in world of architecture

When 14-year-old William Richards ’04 accepted his first summer job as a computer lab proctor, he had no idea it would lead to a lifelong passion. That changed in a moment.

Richards was immediately captivated by the Class of 1945 Library at his high school, Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. Designed by renowned architect Louis Kahn, the library quietly marries local materials, classical concepts like the golden ratio and soaring spaces that are meant to inspire students. It certainly inspired Richards.

“I spent less time doing my actual job and more time wandering around the library,” he said. “It was the first time I really paid attention to how an architect could make careful, thoughtful decisions about materials and the arrangement of spaces. I had no idea what any of it meant, but at the time I remember being struck by the details.”

His stint there set him on a path in art and architecture history that today includes: an award-winning career in writing about the business, culture and practice of architecture, cities and design; three books on architecture, with a fourth on the way; and an editorial and creative consultancy, Team Three, LLC.

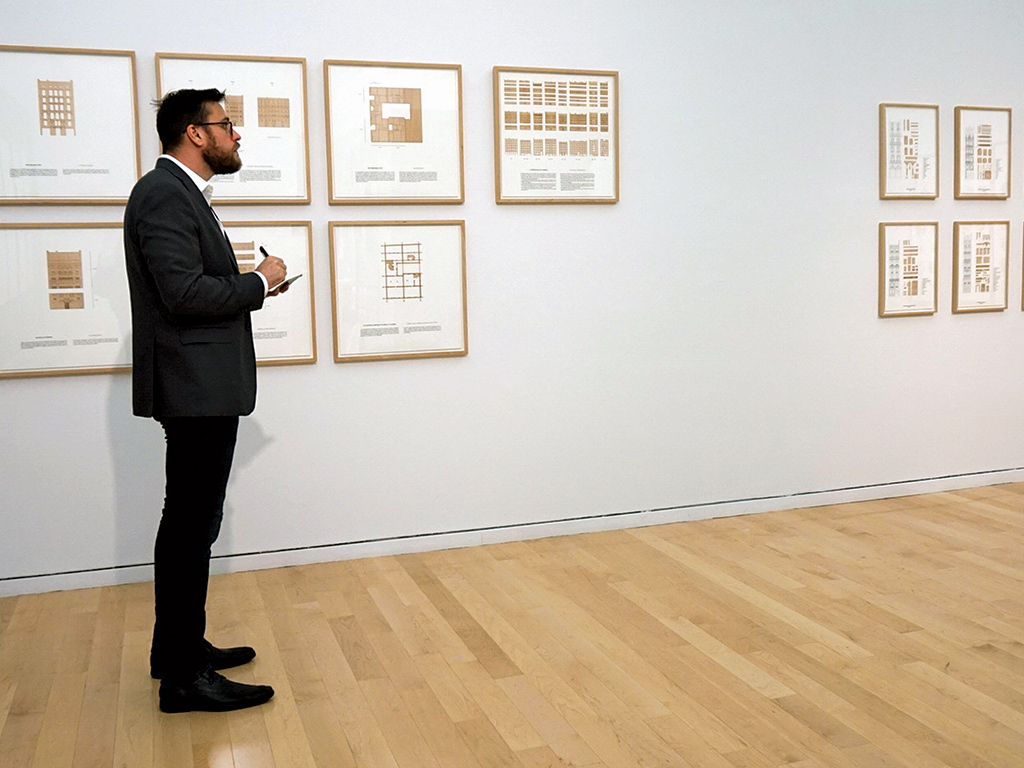

Richards brought all these experiences back to Wheaton in 2021 when he virtually delivered the 13th Annual Mary L. Heuser Lecture. Discussing intentional communities and why the choices we make in living together can enrich the values of the communities we choose, he told current students: “A lot of my work over the years involves spending a great deal of time with architects, learning about their choices, and seeing evidence of those choices in their work.

“Yes, architects are always working within parameters like budgets and codes. Yes, working with clients can be just as challenging as it can be rewarding. But, architecture is a responsibility and a privilege—and through that privilege, architects influence the quality of our lives.”

Setting his own agenda

Richards was drawn to architecture from an early age. Always close at hand today is his mother’s first edition of H.W. Janson’s History of Art. As a young child he gravitated toward the pictures and descriptions of temples, cathedrals and building plans. He knew he would pursue a degree in art history well before he identified Wheaton as the place where he would do it.

He spent his final year of high school at Phillips Exeter Academy exhausting all the electives in art and architectural history, as well as searching for a college that would offer him a world-class art history program. He felt that Wheaton fit his needs perfectly: small classes, a favorable student-teacher ratio and the possibility of finding academic mentorship. He found it all, and then some.

“I feel fortunate to call him a friend and peer these days, but honestly it was often difficult to remember he was an undergraduate during his time at Wheaton,” Professor of the History of Art R. Tripp Evans said of Richards, who enrolled in Evans’s senior seminar as a first-year student.

“Bill had an intellectual maturity and curiosity well beyond his years. He gave the seniors in that seminar a real run for their money,” Evans said.

At Wheaton, Richards took a variety of courses across disciplines—from Caribbean Diaspora and Russia’s pre-war avant-garde to astronomy and logic—following personal interests as often as his art history requirements. He embraced the liberal arts curriculum as an opportunity to set his own academic agenda to succeed or fail on his own terms.

“Exploring history through the lenses of art and architecture fueled my curiosity about lots of things, including different styles of writing,” he explained. “Those fields are as much about physical evidence as they are about ideas—paintings, sculptures and buildings—all illuminated by texts and debates that are mirrors of their times.”

Richards recalled Professor Emerita of the History of Art Evelyn Staudinger as a “mythic figure” at Wheaton, known for her infectious enthusiasm.

“She was important to me because she never let me slide into complacency or laziness,” he explained. “She really helped me see that mutual respect is based in honesty and directness—qualities I really admire and value.”

Professor of Philosophy John Partridge, a mentor to Richards as he completed his philosophy minor and beyond, remembers meeting him in the fall of 2001 in his “Aesthetics” course.

Partridge describes Richards’s writing style as a blend of “clarity and erudition with wit and charm, all while making accessible complicated theories and interpretations.”

Those qualities, both academic and personal, transformed not only the student, but also the professor.

“Almost always, we grow and transform in relationship with others, rather than alone,” Partridge said. “When Bill looked to me for mentorship, I found the opportunity to take on a new role. It’s as if he saw more in me than was there at the time; he surely inspired me to grow into something different.”

The two remain in touch today.

Richards went on to earn a Ph.D. in art and architectural history from the University of Virginia, and, as editor of Inform Magazine, published by the American Institute of Architects’ (AIA)Virginia chapter, he established himself as a thought leader within the architectural community and quickly went on to direct publishing and digital content for AIA’s national operation for nearly a decade.

As a writer for national magazines since college (publishing two pieces of criticism for Art New England Magazine), he has focused on the business, culture and practice of architecture, as well as cities, communities and design. Over the past 20 years, he has written for Architect Magazine, Architectural Record, Art New England, Landscape Architecture Magazine, Old House Journal, Residential Architect and The Providence Journal, among other publications, including several academic journals. From 2013 to 2016, he also covered economic trends, personal finance and retirement planning for CNBC personality Jim Cramer, and later worked as the communications director for economic studies at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.

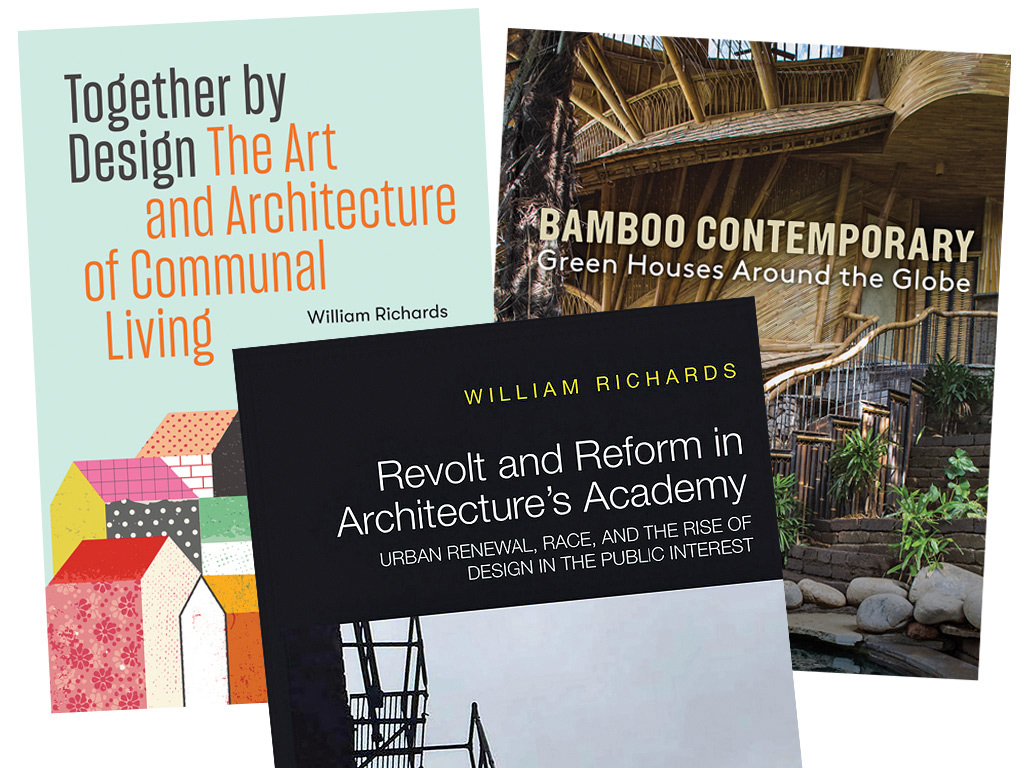

By 2017, Richards published his first book: Revolt and Reform in Architecture’s Academy: Urban Renewal, Race, and the Rise of Design in the Public Interest, adapted from his dissertation at the University of Virginia.

The long format of publishing allowed him to explore more deeply the cultural intersections he first encountered in his studies at Wheaton. Revolt and Reform argues that urban renewal and campus expansion at Columbia and Yale in the 1960s recast architectural education at schools whose host cities, New York and New Haven, were critical sites for political, social and urban upheaval in America. This change, he argues, catalyzed what we call “public interest design” today, or architecture that addresses community participation, equity, health and sustainability.

“Those ideas matter when we find ourselves in an increasingly divisive political landscape, a time when we need to remember our humanity most and find mutually supportive solutions for housing insecurity, structural inequities and environmental injustice for society’s disenfranchised,” Richards said. “Wheaton gave me the latitude to explore a lot of these ideas while I also started—inadvertently—to build a foundation for the rest of my life.”

Sustainable choices

Feeling restless and looking for a change, Richards and his wife and business partner, Pascale Vonier—a graphic designer—decided in 2020 to found Team Three, LLC, their consultancy based in Washington, D.C. Their global client list includes private enterprises (including architectural firms), nonprofit organizations, cultural institutions and universities. Team Three helps their clients communicate more effectively, understand their audiences and raise their visibility on issues that matter, Richards said.

In 2022, Princeton Architectural Press published two more of his books, both on architecture and sustainability: Bamboo Contemporary: Green Houses Around the Globe and Together by Design: The Art and Architecture of Communal Living. The field of sustainability is one in which Richards believes architects can play a leadership role in addressing how the built environment can drive positive climate and social change for communities, streets, cities and regions.

“In designing a building and advising on its construction, for example, architects have influence over the details of design and the values that design represents, which can determine a lot about the quality of our lives as individuals within communities,” Richards explained.

If an architect starts with that value of environmental sustainability, he continued, it can lead to hundreds of choices that make new projects both affordable and green.

“Architecture can also be flexible in the messages it conveys, but it is always certain in its significance as something intentional that shapes all of us. For those reasons, climate, equity, politics and race are foundational to architecture’s creation and why it matters to society,” he said.

Richards’s fourth book, currently in production, explores engineered wood known as mass timber and its promise for use in sustainable residential building projects in the future.

Sharing knowledge

When Richards virtually presented the distinguished Heuser lecture in 2021 about cohousing and architects who keep communities at the center of their work, Staudinger encapsulated the lasting impact of his work thus far.

“The great beauty of teaching is the gift of learning from our students,” Staudinger began, as she described a 2004 talk Richards gave about Hans Holbein’s portrait of Sir Thomas More, a noted Renaissance humanist who emphasized the social potential and agency of humans.

“It was a portrait of a humanist considered to have been one of the greatest scholars of his time,” she continued. “I thank you for the opportunity to listen to your humanist ideas tonight.”

Humanist is likely the perfect way to describe the values Richards places on his chosen path.

“Writers should feel a sense of responsibility and privilege in what they do and how they do it,” he said. “Writing doesn’t always have to be a moral act that’s meant to uphold some broad standard of probity. But I do think writing is an ethical act that reveals as much about ideas as it reveals about the agenda of the writer and the values of the reader.”

To read articles by William Richards, visit williamrichards.net