The art of collaboration

Professors, students engage in multifaceted exploration of Goya, Beethoven

It is not known whether Ludwig van Beethoven and Francisco José Goya y Lucientes ever met. But the fact that their artistic lives were so strikingly parallel and intriguing inspired two Wheaton College professors to team up to teach a set of interdisciplinary courses on the two men.

The fall courses took students from Norton to Boston and New York, immersed them in a world of symphonies and fine art, and had them buying prints, curating an exhibition, attending concerts and learning from renowned experts, including an alumna who co-curated the first North American exhibition of Goya’s work in 25 years.

The collaborative project was, as Professor of Music Ann Sears put it, “a monumental task,” but one in which she and her colleague, Professor of Art History Evelyn Staudinger, “relished every moment.” It was also one that had a profound impact on Wheaton students, who acquired professional skills, made valuable art industry contacts, and greatly benefited from the varied and diverse approach to learning.

“The course has opened my eyes to the social complexities of Beethoven’s music, to the life of Goya—who is nearly a friend at this point—and to the value and wonderful accessibility of art collecting,” said Kathleen “Lena” Sawyer ’15, an art history major. “It’s been quite a ride, but experiential, interdisciplinary learning—especially when mediated by someone like Professor Staudinger and Professor Sears—has proven itself to be far more poignant than simple classroom learning.”

Making the match

For several years, Staudinger had been planning to teach a course on the Spanish painter Goya, knowing that friend and fellow art historian Stephanie Loeb Stepanek ’65 was organizing a major exhibition of Goya’s works at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where she is curator of prints and drawings. After about a decade of planning, “Goya: Order and Disorder” opened at the MFA on Oct. 12, 2014.

Sears had already taught courses on Beethoven—one of her favorite subjects to teach. And when the two began talking about wanting to engage in something new and creative at this point in their long teaching careers, a partnership began to take shape.

Goya was born in Spain in 1746, while Beethoven was born in Germany in 1770. They died within a year of each other—Beethoven in 1827 and Goya in 1828. They also shared a devastating loss: Both men went deaf, a few years apart, Beethoven at 26 and Goya at 47. And the similarities didn’t end there.

“Both heralded in the period of Romanticism in art and music, creating works that had never been seen nor heard before. At first producing art and music for a primarily aristocratic audience, their art crossed social boundaries by the end of their careers,” Staudinger said. “Both had political views that were largely shaped by the Enlightenment and later the Napoleonic wars, and that informed their work to a far deeper degree than their predecessors. As a result, each created paintings/prints and music that at times could have been interpreted as politically and socially subversive.”

Inspired by these commonalities, the professors applied last winter to co-direct the Wheaton Institute for the Interdisciplinary Humanities (WIIH) in 2014–15, planning to teach their music and art history courses collaboratively, cross-lecturing to each other’s classes, bringing in outside speakers, and organizing a number of events and trips to bring their lessons into the real world.

Founded in 2012 by Associate Professor of Art History Touba Ghadessi and Associate Professor of History Yuen-Gen Liang, the WIIH gives students the opportunity to develop professional skills while focusing on an interdisciplinary theme in the humanities; Wheaton is one of only a dozen undergraduate institutions in the country to have a humanities center, and it is unique in its central focus on undergraduate education and professionalization. Past WIIH courses have tied together the humanities and professional fields such as medicine, business, engineering and law, as well as illustrated how the humanities are in active dialogues with new media and technologies. Students enrolled in WIIH courses become WIIH Fellows and employ the knowledge they learn in the classroom by conceptualizing, organizing and promoting WIIH events that are often open to the larger public. Essentially, the WIIH helps students acquire real-world skills by bridging academic studies and the professional world.

“We thought it would be a wonderful challenge,” Staudinger said of co-directing the WIIH with Sears. “We both love the humanities and the arts, and we thought we’d work really well together. With a groundbreaking show set to open in Boston at the same time, tying together Goya, Beethoven and the WIIH just made sense.”

“Beethoven is such an iconic composer. His music has been used by so many different constituencies to convey so many different messages, and the music is extraordinarily memorable,” Sears said. “With the chance to collaborate in an even more interdisciplinary way than usual with Evie’s class on Goya, and the fact that this enormous exhibit was opening at the MFA, it was really a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Rock stars and symphonies

Students taking Sears’s and Staudinger’s WIIH courses were required to participate in a minimum of seven activities outside of class. The busy schedule kicked off in September with a trip to hear the Boston Symphony Orchestra perform the music of Beethoven and Mozart.

Deanna White ’15, an art history major, said the symphony performance was one of her favorite activities.

“I’ve always loved listening to classical music, and now, after learning about Beethoven and doing a lot of research on his life, it felt like I finally got it. I hear the nuances that he was going for. I was able to see why what he was doing was so phenomenal at the time and why it still resonates in Western culture today,” she said.

In early October, Goya scholar Janis Tomlinson visited campus to give a guest lecture titled “The Changing Image of Goya: Recent Discoveries and New Questions.” In her talk, Tomlinson, currently the director of university museums at the University of Delaware, used letters, news clippings, sketchbooks, biographies and the artwork to unpack myths about Goya, who has been called, among other things, a rabble-rouser, revolutionary, intellectual, family man and artist in crisis.

In introducing Tomlinson, Staudinger referred to her as the students’ “intellectual equivalent of a Goya rock star.” Tomlinson has written numerous books and papers on the artist, including two textbooks used in the Goya class.

Tomlinson’s talk was dedicated to the late Eleanor Sayre, former curator of prints and drawings at the MFA and someone who helped nurture a love of Goya in Tomlinson, as well as in Staudinger and Stepanek.

The WIIH schedule also included several campus concerts featuring the music of Beethoven, such as an October 8 performance by pianist Victor Rosenbaum, who taught several Wheaton faculty members, including Sears. After playing an all-Beethoven concert, Rosenbaum stayed for about two hours to talk with students about music, Beethoven and his professional life.

In December, shortly before the end of the term, Stepanek—the woman behind the groundbreaking MFA exhibition—came to campus to give a talk titled “Goya’s Ingenious Arrangements: Imagined Worlds.” Her talk was the seventh in the Mary L. Heuser Lecture Series, named for the late art history professor, who was one of Stepanek’s closest mentors at Wheaton.

Getting close to Goya

In late October, more than 200 Wheaton students, faculty, staff and alumnae/i, including Stepanek, joined President Dennis M. Hanno for a special reception at the MFA. Staudinger gave the evening’s featured talk—a lively illustrated discussion of Goya that she dedicated to Stepanek and Sayre.

“Every single work by Goya has voice—always an active one, never passive: This is not to say just one, nor that each speaks a single language nor sings the same song, articulates a single message or creates vibrations that are emitted from only Goya’s vocal chords,” Staudinger told the audience before they set off to explore the exhibition. “In fact, often and especially in his private work, it will be you and he, witnessing, watching, snooping and eavesdropping side by side in front of his art, craning to hear the third presence: that of humanity…”

Staudinger praised Stepanek for her part in bringing the exhibition to life, saying the alumna’s “exquisite scholarly voice is present in every audible and inaudible decibel as you walk through the Gund galleries: discernible in the wall text, heard in the audiotapes, emanating from the exceptional choices of juxtaposed artworks, even embedded in the choice of wall colors (the most stunning of any show I have ever seen).”

Students attending the event wore buttons with an image of Beethoven or Goya that represented a print they were working on for an upcoming student-curated exhibition at Wheaton. After the talk, they toured the galleries, which showcased 170 of Goya’s paintings, prints and drawings, including 71 works from the MFA and numerous loans from major museums and private collections around the world.

“We got a chance to network with alums and other members of the museum community in Boston,” art history major Michael Williams ’16 said. “That was pretty interesting, and it opened my eyes to see what other people are doing with art history degrees.”

The tour itself was also memorable.

“It was like being in class, but instead of being on the projector screen the picture that we were studying was in full size right in front of us. It was pretty incredible,” Williams said.

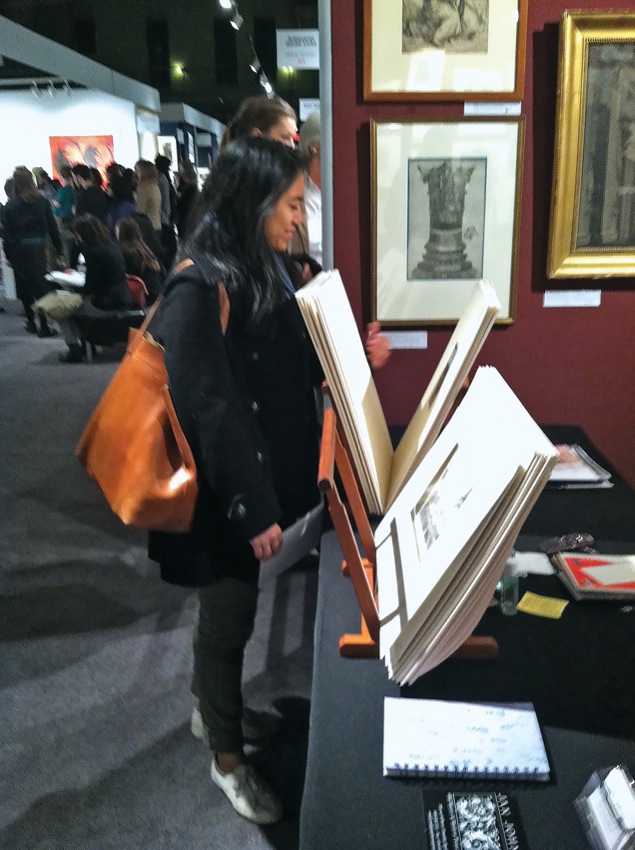

About a week later, the art history students had a second opportunity to get up close and personal with the works of Goya. With support from Wheaton College Friends of Art, the class took a bus to New York City for the annual International Fine Print Dealers Association Print Fair. There, students were divided into groups and sent on a mission: to view the Goya prints available for purchase and select two—one that would be added to the college’s Permanent Collection and one that would be the first Goya print in Staudinger’s private collection.

Though she gave them a few guidelines, including price limit, Staudinger left the decision up to the students, who returned after their hunt to debate the final purchases as a group. In the end, they chose for Staudinger exactly the print she had had her eye on—”Disparante Volante” from Goya’s Disparates series—as well as a print she felt would be a perfect addition to the Wheaton collection—”Que Valor” from the artist’s Disasters of War series.

“Both of the prints were exactly the ones I wanted,” Staudinger said. “It was like mental telepathy. And the students were joyous to have this particular opportunity to buy something for Wheaton.”

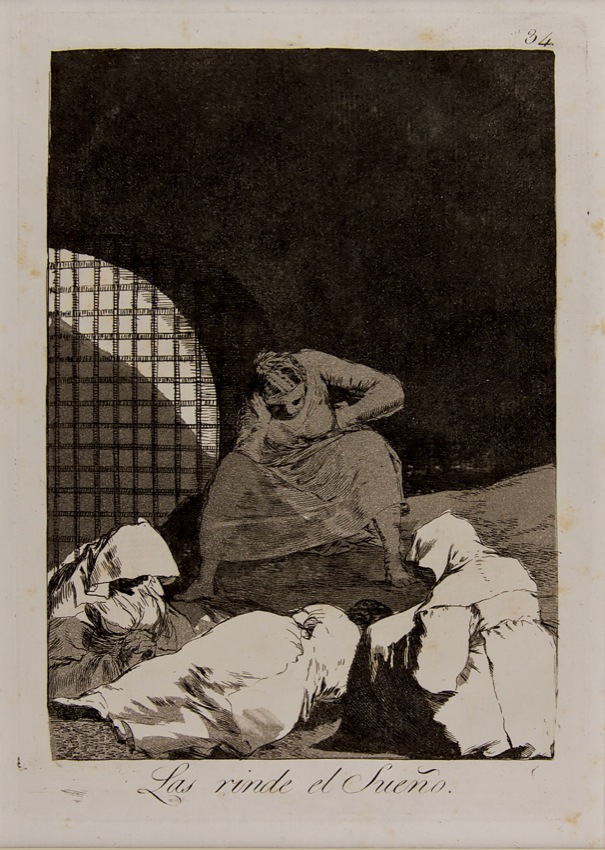

The Wheaton print, purchased with funds donated by Kathy Foley Denniston ’73 and by Friends of Art, was given to the collection in honor of Stepanek. In class, the students selected a second print for the Permanent Collection, “Las Rinde el Sueño,” which was also purchased with funds from Denniston.

The print fair trip was a semester highlight for several of the students, including prospective art history major Sarah Chin ’18.

“I’ve never had the opportunity to be physically up close and observe—like, within arm’s reach—Goyas without alarms going off. It was great to see them and to hear from people who are so passionate about prints,” Chin said.

The humanities at work

The Goya/Beethoven collaboration certainly met the WIIH goal of providing opportunities for students to develop their professional skills. Students enrolled in the two classes were in charge of organizing an exhibition in Wheaton’s Weil Gallery that showcased Goya’s prints and Beethoven’s music. It was accompanied in the Beard Gallery by “Tracing the Thread,” another exhibition curated by the students enrolled in “Exhibition Design,” which was co-taught by Professor Leah Niederstadt and Wheaton archivists Zephorene Stickney and Megan Wheaton-Book.

Titled “Goya and Beethoven: Finding a Voice Out of Silence,” Sears’s and Staudinger’s classes’ exhibition opened November 19 and featured 19 Goya prints as well as nine portraits of Beethoven and his contemporaries, and two prints after Goya by contemporary artist Emily Lombardo. While nine works were from Wheaton’s Permanent Collection, the remaining items were on loan from Amherst, Smith and Wellesley colleges and four private collections, including an extensive collection of fine musical portraits from Stephen Bergquist, a Goya print from Stepanek and a book of prints from Karen Greenland Dyer ’60.

Together, Sears’s music students and Staudinger’s art history students curated, installed and promoted the exhibition. Art history students wrote the wall text, and music students recorded statements about Beethoven as well as a short track of the composer’s music to accompany several of the images. Gallery visitors could listen to the recordings by scanning a QR code with a smartphone.

White helped curate the prints of Beethoven and his contemporaries.

“The artist who worked on the portraits of Beethoven did a really good job of showing how dignified and intelligent and powerful he was, the same way that Goya was portraying his own power and voice through his works,” the senior said. “So there’s some nice intersection between these two men, who were both adjusting to a new lifestyle after going deaf and were able to capture that in their art and music.”

Nicolas Sterner ’16, a music major, also appreciated the way the exhibition highlighted the links between the two men.

“Like Goya, Beethoven started with a blank canvas, although the canvas was very different for both artists,” Sterner said. “Beethoven starts with silence as his blank canvas and paints sound over that, whereas Goya uses literally a blank canvas or sketchbook or the many mediums he worked with.”

A semester to remember

By the final weeks of the semester, when many might be drained of enthusiasm for even the most exciting of courses, the WIIH students were still raving about the experience to their professors.

As art history major Julia Dry ’15 put it: “It challenged me to approach an artist and his work in an unconventional manner. We drew from external academic disciplines, experienced vastly different learning techniques and had the opportunity to consult with scholars. With the hands-on and discussion-based design of this course, I was able to discover dimensions of a topic I would otherwise look over in a traditional seminar class.”

Elliot Anderson ’18, a music major who plans to double major in neuroscience, also found the course impactful.

“I wasn’t even that interested in Beethoven’s work at first, but I knew there was something that would inspire me by studying him, and within the first week, even just reading the textbook, I wanted to get up and go to a piano and start playing his music,” Anderson said.

The semester didn’t just engage soon-to-be Wheaton grads—Sears and Staudinger taught a series of Goya and Beethoven lectures to members of the community through the Norton Institute for Continuing Education (NICE), and several of their adult students attended some of the WIIH events on campus, including Stepanek’s December talk.

The project also had an impact on the two people who started it all.

“Being part of the WIIH has done something really extraordinary for me as well as the students,” Sears said. “I’ve been at Wheaton a long time. This is my 34th year teaching here. But I feel recharged and reinvigorated.”

Staudinger agreed, calling the teaching experience “one of my two most rewarding ever.”

The professors also appreciated the chance to champion a cause they feel strongly about: the humanities.

“Studying the arts is one of the primary ways we try to understand cultures,” Sears said. “So past and present, we’ve got pretty good evidence that the humanities are an important part of a liberal arts education and that our students are the ones who are equipped to go out and transform the world.”

Staudinger hopes the courses will help promote the humanities as a discipline that connects to many others, from science to mathematics to technology. She also hopes students see the great value of studying art history.

“A lot of first-year students don’t know what art history is and don’t think of it automatically as a discipline. This was a nice chance to be able to say: This is a discipline that without question will help you understand your world better since you live in a densely visual one. Moreover, studying the art of Goya will provide you with a window into the complexities of humankind and therefore into yourselves,” she said.

For both women, the WIIH teaching experience is just one example of what has kept them at Wheaton all these years.

“I’m still here because not only do I get to teach here, I get to learn here,” Sears said. “That’s why I believe in the humanities, because not only do I see what has happened to students who graduate from here, but I see what a difference it has made in my own life.”

Sharing Goya

Stephanie Loeb Stepanek ’65 reflects on career, Boston art exhibition

That vote of confidence helped Stepanek land her first job: secretary in the MFA’s Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

Today, Stepanek is the MFA’s curator of prints and drawings—the same title Sayre once held. And this fall, Stepanek saw the completion of a project Sayre would have wholeheartedly approved of—the opening of a groundbreaking exhibition of the works of Spanish artist Francisco José Goya y Lucientes.

“She was a major Goya scholar of international reputation, and she contributed to many publications on the artist,” Stepanek said of Sayre. “She made strong acquisitions in Goya for the MFA, and she fostered two major exhibitions, both of which I worked on with her.”

For about a decade, Stepanek has been working on a Goya project of her own: pulling together a broad retrospective of the artist’s work spanning his entire career. The resulting exhibition, “Goya: Order and Disorder,” which she designed with fellow MFA curator Frederick Ilchman, features 170 of Goya’s most significant paintings, prints and drawings, including rare drawings and working proofs from the MFA collection as well as loans from museums and private collections around the world.

“Goya worked in turbulent times and everything was changing—the old order was giving way to the new order and Neoclassicism was turning into Romanticism, the styles of art were changing, the styles of thought were changing, so during this change Goya through his art was trying to confer a kind of order on this messy, chaotic world around him,” Stepanek said of the exhibition’s title.

As an undergraduate at Wheaton, Stepanek loved art but was leaning toward a career in literature.

“I thought I would want to be an art editor in publishing, but I soon found out that the jobs that were available at the time were in book production and buying paper for books, and that seemed a little boring for me,” she said. “When I interviewed for the MFA job, it became clear to me that I really did want to work in a museum, and since the day I started I have never regretted it.”

Along with the mentorship of people like Bush, Stepanek credits her Wheaton education with preparing her for a successful career.

“The art history major at that time was very strong, and I’m sure it still is,” Stepanek said. “I recall at the end of my education, we had nine hours of exams—more than any other major. Three of those hours were devoted to iconography, the study of the meaning of things, and that prepared me very much for my job.”

In December, Stepanek returned to Wheaton to give a talk, “Goya’s Ingenious Arrangements: Imagined Worlds,” as part of the Mary L. Heuser Lecture Series, named for another of her Wheaton mentors.

“It was like coming full circle,” Stepanek said of giving the talk. “I was glad to be able to contribute to cultural life at Wheaton. As and art history major, I was inspired by Mary Heuser’s courses at Wheaton and maintained a friendship with her until her death.”

Photos by Keith Nordstrom