Summer of science at Wheaton

Faculty-student research grants encourage collaboration, experiential exploration

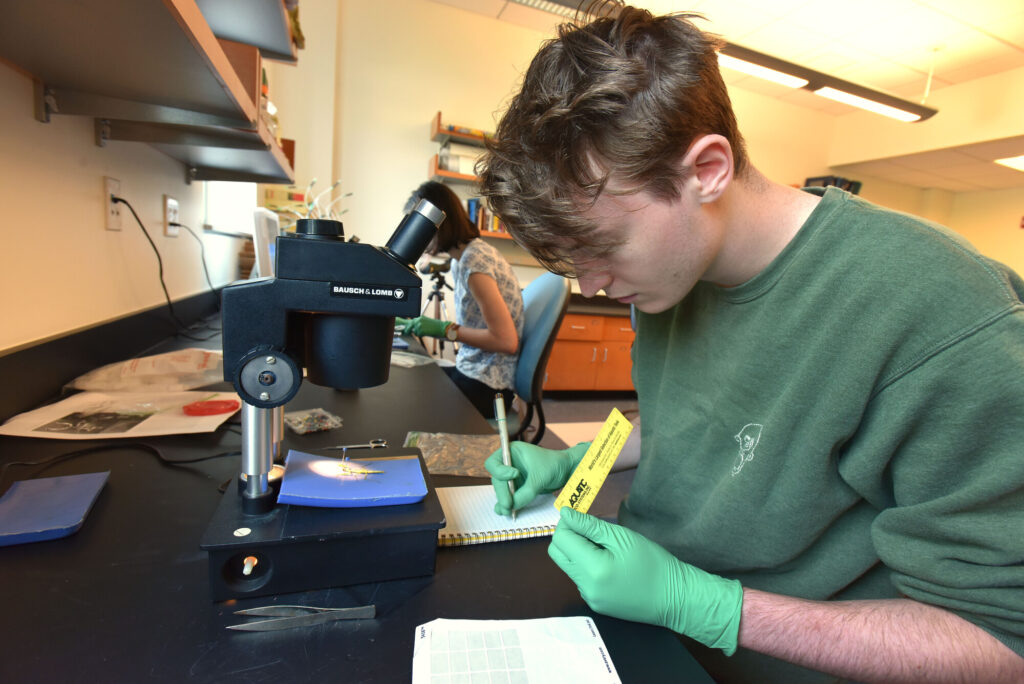

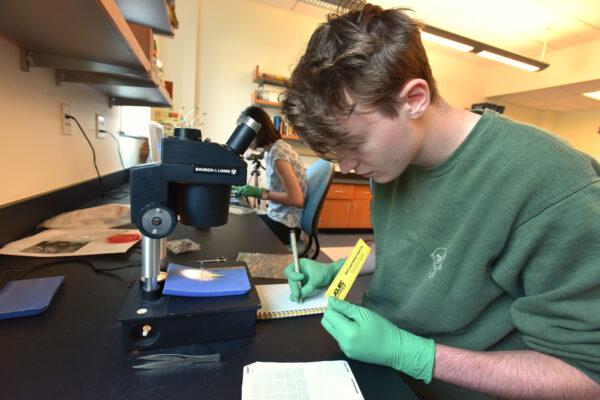

On a 90-degree day in July that was perfect for stretching out on the beach, two groups of Wheaton students instead were perched over microscopes, specimens and measuring apparatus engrossed in research projects in labs in the Mars Center for Science and Technology.

In Room 2120, Eleanor Ruhlin ’22, Julianna Bauer ’22, Samantha Teixeira ’23 and Adi Shmerling ’22 were preparing specimens for Assistant Professor of Biology Jessie Knowlton’s research on the impacts of invasive praying mantids on native arthropod communities in southeastern Massachusetts.

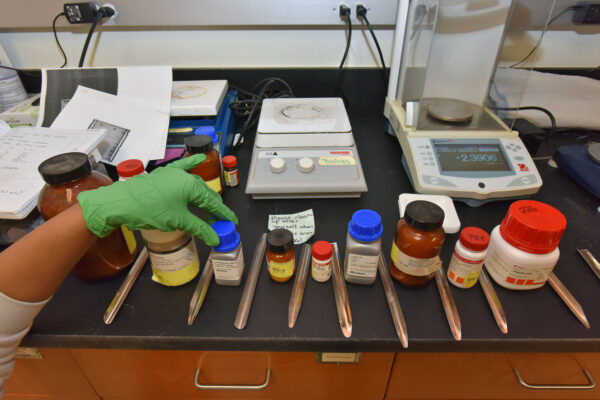

Nearby in Room 2113, Melane Goncalves ’22 and Meghan Reed ’22 were working on a project helping Assistant Professor of Biology Primrose Boynton establish a baseline collection of yeast specimens to compare against future yeast in the changing New England climate. Image gallery below

Goncalves enjoyed taking Professor Boynton’s “Microbiology” course and was excited for the opportunity to work with her this summer.

“I felt like it would be a great experience to work in the lab as a team and with a professor in a professional setting other than the classroom,” Goncalves said. “This will be something good to have on my résumé and, also, I like being around people that I enjoy.”

The work by both groups is supported by faculty-student research awards, 13 of which were granted for 2021 to provide stipends for collaborative summer projects. Several departments were represented, including biology, chemistry, visual art and history of art, psychology, women’s and gender studies, physics, and business and management.

The opportunity is provided to foster either new research, in which faculty members and students collaborate on a project they have designed together, or ongoing faculty scholarship, for which students are employed as collaborative researchers.

Professor Knowlton has her attention focused on an introduced predator in New England—the praying mantis—and how this little insect might have big impacts on our native bees, butterflies and other pollinators.

“This is important because many predators are found to have ‘keystone’ effects on the larger community, sometimes causing drastic changes to community structure and food web interactions,” Knowlton wrote in her award application. “This project relates to my larger body of work because I focus on human-mediated changes to the environment and the impact these have on other species, including birds, mammals and insects.”

In the lab, Ruhlin, Bauer, Teixeira and Shmerling discussed their collaboration, including the field work in which they collected praying mantids by hand from local fields, the importance of the research and how it relates to their educational goals. (Erin Ortega ’23, who was not in the lab at the time, is also a collaborating team member.)

“Basically, we’re trying to see whether or not mantises are causing a lot of damage to the ecosystem or whether it’s a minimal amount. We’re looking at what they’re feeding on, how they’re affecting the environment, and how we can use that information to maybe control them in the future if it becomes an out-of-control situation and we need something to be done about the invasive organisms,” said Shmerling, a biology major.

Meanwhile, Professor Boynton is studying two types of yeasts to see how they change over time to get a better understanding of responses to climate change.

“Climate change is currently one of the timeliest agents of biological change: average annual temperatures in New England are predicted to increase one to four degrees Celsius by 2100. Scientists expect organisms living in New England forests to respond by adapting in pace to increased temperatures, shifting northward as the climate warms, or dying off,” she states in her faculty-student research award application.

Reed and Goncalves began collaborating with her on the research in May and continued through July.

“We are looking for Saccharomyces yeast [a single celled fungus] in the Wheaton Woods, specifically in Massachusetts, because it hasn’t been tested here before,” said Reed, standing at a lab counter in the Mars Science Center with her partner. “Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a type of yeast that you find in bread, beer and wine. It has a sister Saccharomyces paradoxus that has been studied; it’s the wild-type yeast. We’re looking for those two species of yeast here.”

As the two students collect and analyze samples and freeze them for future research, they play off of each other by asking questions designed to inspire their own independent research while collaborating with their professor on hers, which they say has been valuable.

Like her partner, Reed also values the experiential opportunity. “I am a biology major. I want to go to grad school for something microbiology-related. This is a good beginning to the kind of research I want to do in the future. I’m learning a lot of skills.”