Political science

The world’s biggest problems won’t be solved by politicians alone—experts and advocates from many different fields need to come together to look at the facts, argue their respective sides and come up with solutions.

That’s why professors Geoffrey Collins and Adam Irish are bringing today’s international relations and geology students—tomorrow’s leaders—together in one room to debate real environmental issues in a simulated negotiation that shows them just how complicated yet important these interactions are.

“For a lot of students, it’s hard to understand that when you confront a problem like watersheds or climate change—and for my money I think these are the problems that will define our next century—these aren’t problems that coercion or single-state behavior can solve. These are collaborative, cooperative issues,” said Irish, whose International Politics students are paired up with students in Collins’ Geology course through the Politics and Global Change course Connection.

Collins began doing the simulations several years ago with now-retired political science professor Darlene Boroviak, having their students look at issues ranging from the Antarctic Treaty to the United Nations Law of the Sea.

“We wanted to come up with a Connection that would emphasize the fact that many of the pieces of politics that cut across international boundaries have to do with these global environmental problems that confront us,” Collins said. “At the same time, I wanted my students to realize that you can know all kinds of things about scientific theories but when it comes to actually making decisions about things in the real world, science doesn’t always rule the decision-making process.”

Recently, Collins began collaborating with Irish on a simulation that asks students to negotiate international treaties among nations that share a river basin.

“This is especially important as we go into the future, because many of the climate models show some of these river basins starting to dry out in the future. So as population grows and water becomes more scarce, the idea is for countries in these river basins to agree on the principles of how they’re going to share this resource,” Collins said.

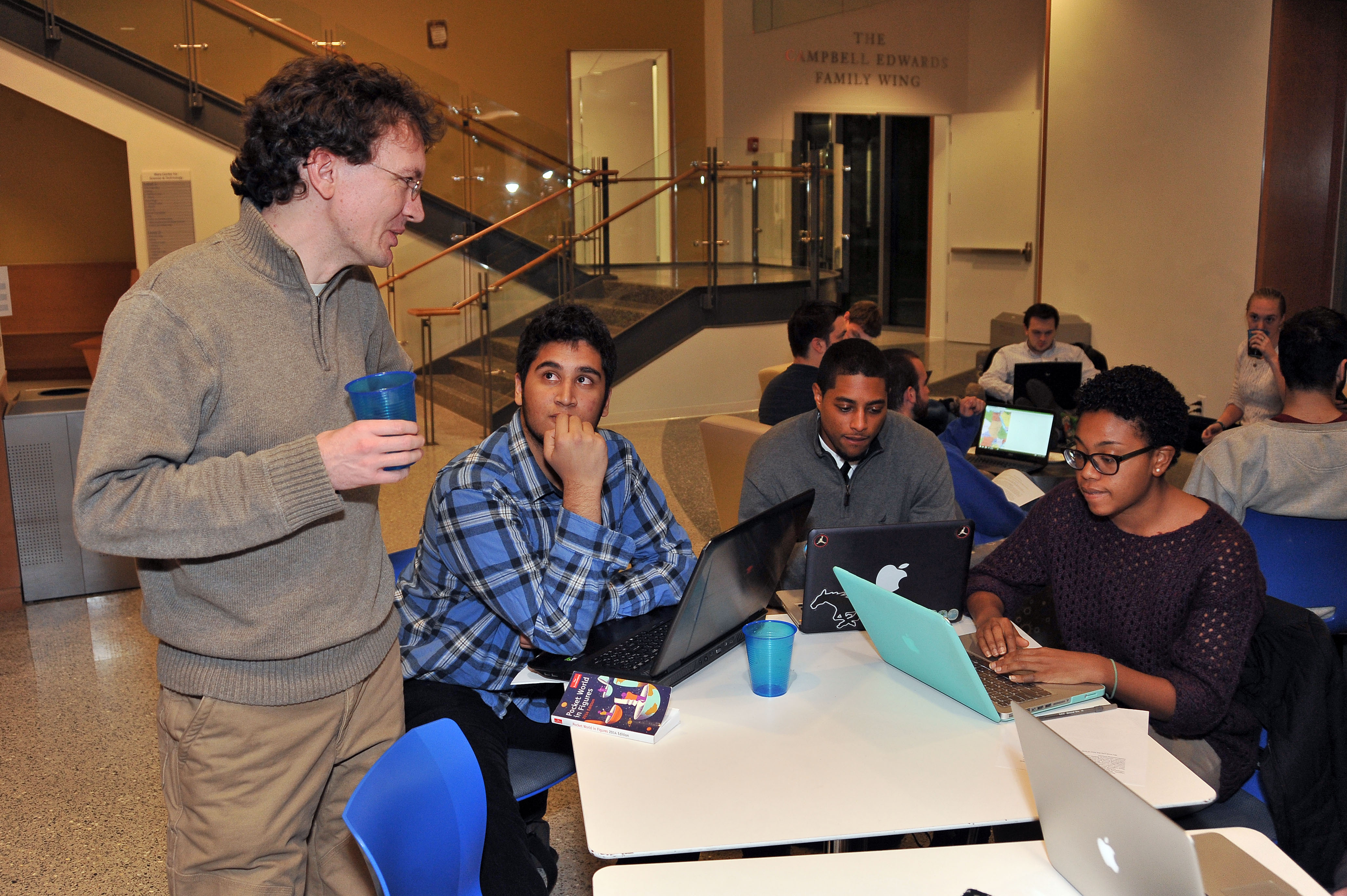

Students were assigned one of eight different river basins around the world and given a role to play, either a representative of one of the connected countries or a scientific expert. On November 20, the students gathered in the Diana Davis Spencer Café where, fueled by pizza, they held their negotiations.

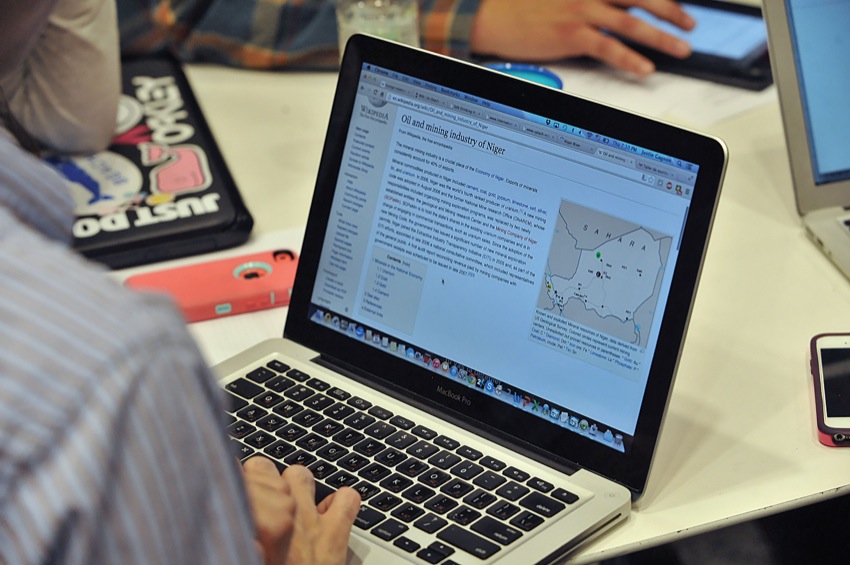

Daniela Pena ’18, an intended political science major, represented Mali in a debate over the Niger River and said the biggest challenge was considering how the needs of other nations affected her country. Though the group understood the need to reduce pollution, they also dealt with the reality that they were among the poorest countries in the world.

“When we are in class we have tunnel vision just seeing what is done in our discipline and don’t get exposed to how what we’re learning relates to the rest of the world and to other professions and disciplines. When you make connections like we have done, you see how different subjects can relate and interact,” Pena said. “This simulation really put world issues into perspective for us and made us aware that it’s not all about political theory.”

Shiwei Huang ’15, a math and economics major, played the role of a scientist in a group that discussed the Amur River, shared by China, Russia and Mongolia. Huang’s biggest obstacle was trying to convince the participating nations to consider the negative impact of building a dam.

“We had an agreement that building a hydroelectric power dam would seriously affect the environment. However, from a political science perspective, getting the dam sometimes is more important than the environmental issue,” Huang said.

For Victor John ’15, an international relations major, the conversation turned toward other topics, such as the threat of ISIS in Iran, Iraq and Syria. In the end, his group agreed on shared use of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in exchange for a military agreement—a diversion that spurred Irish to point out the need for strict agendas for these types of multi-nation negotiations.

“I think political scientists should talk to real scientists more,” John said. “The more we can encourage understanding and discussion across disciplinary lines, the better we can understand and eventually solve the issues and conflicts that we face today.”

Maggie McDonough ’15, an environmental science major, advised countries in the Brahmaptura and Ganges River Basin—including Bhutan, China, India, Bangladesh and Nepal. One of the challenges was getting all players to understand how the actions or inactions of one country upstream could affect countries downstream.

“A large part of our discussion surrounded China and China’s motivation to build a dam for hydroelectric power, but this would alter the flow and power of the river for the countries downstream,” McDonough said. “We came to the agreement that if China were to be allowed to build this dam, they would have to assist other nations like Bangladesh in terms of clean water supplies and economic help due to the loss of fish from the dam, which is a huge part of their economy.”

McDonough was on the other side of the debate when she took International Politics her freshman year and called the simulation “an interesting approach to a complex problem.”

“As a scientist, and going into a profession in the environmental science area next year, it is rare that I will only have to communicate and deal with other scientists,” she said. “The approach Wheaton is taking, which involves the connecting of multiple disciplines, allows us to examine an issue from both sides of the coin.”