Navigating the virtual frontier

Professors and students explore AI

As a student in Wheaton College’s “Digital Marketing” course, Amelia Butler ’24 needed to make a marketing pitch deck to be entered into a global business competition. The challenge: create a promotional plan for a product called Sole Search that parents can use to track their children’s locations.

The final presentation from Butler and her teammates stood out for the many pictures it contained to illustrate their vision—all of which were created using artificial intelligence by typing phrases such as “kid walking alone to school” and “kid walking alone in the city” into the image-generation programs Canva and Midjourney.

“These really helped our campaign,” Butler says. “If you don’t have the budget or resources to create real-life images, pictures or videos to launch a product, or you’re just starting out as a business, AI definitely is an advantage.”

The team came in third in the Fall 2023 Digital Marketing Competition hosted by Purdue University Northwest’s College of Business.

The competition is just one way Senior Professor of the Practice of Business and Management C.C. Chapman, who teaches the “Digital Marketing” course, has embraced AI in the classroom. He also has assigned students to come up with ideas for Google Ads text using the chatbot program ChatGPT, and has added a section to his syllabus encouraging students to use AI for coursework as long as they disclose it.

“Humans are always going to find shortcuts; we love shortcuts, right?” Chapman says. “But it’s about figuring out how to use the shortcut effectively. We can’t not teach our students, because they’re going to graduate and be behind if they don’t know how to use it.”

Butler and Chapman are among the many Wheaton students, professors and administrators who are navigating the sudden ubiquity of ChatGPT and other forms of generative AI—artificial intelligence systems that can be instructed to generate remarkably professional text, images and other media.

The business program is just one of the Wheaton departments where AI is being incorporated into the classroom, with some professors revamping their existing courses to add an AI component and others creating entirely new courses around it.

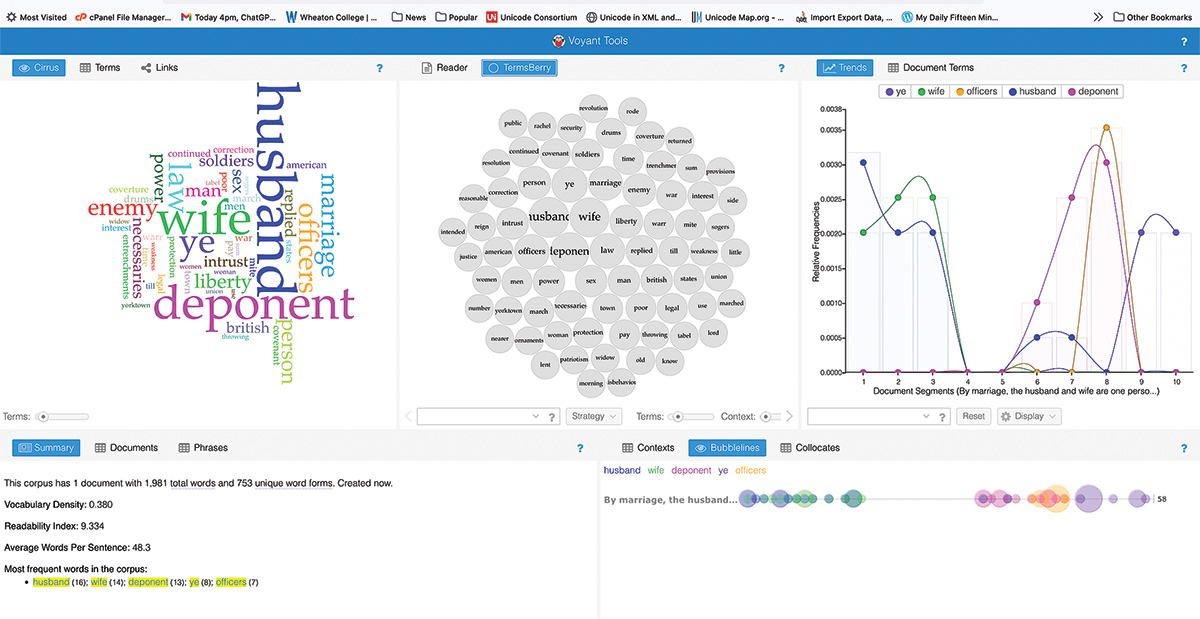

In the History Department, Professor Kathryn Tomasek has revised her “U.S. Women, 1790–1890” course to incorporate multiple AI tools. For one assignment, students used a program called Voyant Tools that analyzes texts to identify word patterns, and for another they got editing help on a rough draft of an essay from the program Notion.

In the Biology Department, Assistant Professor of Biology Andrew Davinack investigated the chatbot for an academic article titled “Can ChatGPT be leveraged for taxonomic investigations? Potential and limitations of a new technology.”

“The molecular revolution transformed the field of taxonomy not too long ago by providing an additional tool for describing and cataloging Earth’s biodiversity,” Davinack notes in the article, which was published in the April issue of the journal Zootaxa. “The implementation of artificial intelligence may very well be the next frontier for this science should all the right stars align: funding, buy-in from taxonomists and natural history museums and improvements in learning algorithms.”

Davinack has also used AI in teaching his course BIO 241: Biological Data Analysis. “I gave students the option of debugging their code by using ChatGPT 3.5 to detect errors. Some students used it while others did not. I hope to make this a staple when I teach the course next fall,” he says.

The exploration of AI at Wheaton reflects what’s happening across higher education. A recent survey by the publisher Wiley found 58% of college instructors say generative AI is already being used in their classrooms, with another third saying they may use it in the future.

Currently, Wheaton faculty members are encouraged to have explicit policies regarding students’ use of generative AI in their syllabi, says Josh Stenger, associate provost. These policies may vary in some respects but must be consistent with the college’s broader policy on plagiarism, which forbids “representing the work, words and/or ideas of another (including work created by generative artificial intelligence) as one’s own.” The Advisory Committee—a panel of five faculty members that helps craft policy for the college—has been in conversation with President Michaele Whelan about the development of institution wide guidelines and standards, Stenger says.

“It really is like standing on the beach and you’re seeing this giant wave that’s coming,” says Professor of English Lisa Lebduska, a widely acknowledged campus leader on AI issues. At the same time, she stresses that most people are already using AI even if they aren’t describing it that way—think of autocorrect on a text message, or Gmail suggesting how to complete a sentence.

“It’s there. It’s not going away,” Lebduska says. “And so for me the idea is, OK, how do we make this into something good? What can I show my students, what questions can I encourage them to ask?”

As director of college writing, Lebduska has been tackling one of the biggest conundrums related to AI: the search for constructive ways of using chatbots that still ensure students develop their own writing skills. She thinks ChatGPT could be particularly useful for students who need help organizing their thoughts—often a pain point for novice writers—because it can create outlines that jump-start them on assignments.

The challenge, said Lebduska, is that “faculty members must assess where students are in their development and to what extent struggling helps students to develop both their organizational skills and resilience and to what extent students are at risk of shutting down. Fast and easy isn’t always the goal, nor is endless toil.”

Some students say they are turning to AI regularly to complete assignments, though others say it hasn’t become part of their routine yet.

Butler, a business and management major, says one way ChatGPT has helped her academically is in breaking down advanced texts assigned by her professors. She will sometimes plug a complex reading into the chatbot and have it generate a summary in plainer language to ensure she has understood the crux of the text.

“I use it for everything I can,” Butler says of ChatGPT.

By contrast, Joshua Nangle ’25 says his professors have mostly discouraged students from using ChatGPT—and he himself shares their skepticism.

“Honestly, I’ve never downloaded it,” says Nangle, a political science major, with a laugh. “I’m just too paranoid about what that would entail.”

For many, the lightbulb moment regarding AI’s transformative potential came when ChatGPT was released publicly in November 2022. But for Associate Professor of Filmmaking Patrick Johnson, the moment had come about six months earlier.

Johnson was on sabbatical researching how to teach students the skills needed to master the type of 3D virtual production software used to make Disney’s “The Mandalorian.” So, he decided to get access to DALL-E 2, a cousin of ChatGPT that creates images from text prompts.

“It immediately hit me that many of the skills and things that I was doing in 3D software were getting sort of swept aside and made totally irrelevant by this,” Johnson says.

After that, he began incorporating AI into his “Production I” course, which is offered each semester. One assignment in the course asks students to create an original short film, and in the past they had sometimes struggled to come up with story ideas.

Now, Johnson asks them to go to ChatGPT and input the prompt, “Give me 10 ideas for a short film that involves two actors on a college campus.” They follow up by asking the program to flesh out their favorite of the 10 ideas, then take ChatGPT’s basic outline and use it to write their own script.

“For those who struggle with creative ideation, it just offloads a lot of that stress,” Johnson says.

Samar El-Taha ’25, who took “Production I” last spring, says Johnson was the first of her professors to put forward AI “as a tool instead of a threat,” and she found ChatGPT’s script ideas provided a way of “getting your creative juices flowing.”

“I think in general Wheaton is a school that’s pretty open-minded about everything,” El-Taha says. “So it doesn’t surprise me that they’re not immediately quick to demonize AI or ban it outright.”

Yet, Johnson himself experienced the limits of AI technology last summer when he tried to create a new work using as much generative AI material as possible. He ultimately found the project unfulfilling as an artist, and was left wondering, “What is the way in which this technology can be used that still maintains that love of the craft, love of the medium?”

Professor of Computer Science Mark LeBlanc—who has been studying AI since he was a graduate student in the 1990s—is impressed by the advances that ChatGPT, Google Bard and similar systems have made. But he is also keenly aware of their limits.

In his new First-Year Experience course “AI, Big Data and You,” LeBlanc emphasizes that they are all probabilistic models, simply guessing what word to spit out next based on the millions of existing books, articles, websites and other material they’ve been trained on.

LeBlanc offers an example he uses in class: if you ask a generative AI program to finish the phrase “cat in the,” the program will almost certainly suggest “hat”—even though “tree” or “box” could work, too. However, those two words have followed much less frequently in the bot’s training.

“The bots generate responses based primarily on the examples that were used when the bot’s large language model was trained,” says LeBlanc, who in November 2023 presented ChatGPT workshops at the Boyden Library in Foxborough, Mass., and Norton Public Library.

In his “Foundations of Computing Theory” course, LeBlanc instructs students to use ChatGPT to generate an algorithm, then asks them to verify and annotate the accuracy of the coding. He wants them to see that AI systems can make mistakes, even small ones and that being able to spot those errors is a crucial skill.

“I’m all for ChatGPT getting it almost correct, because it’s making my point exactly,” LeBlanc says. He likes to quote the late Fred Kollett, who was founding director of Wheaton’s Academic Computing Center: “In computing, if you are almost correct you are a liability.”

“What we’re trying to do,” LeBlanc says, “is show them that, at least for now, you’re better than the bot.”