Inside-Out course removes barriers

Students learn together in a class that was ‘exactly the same and entirely different, all at the same time’

From the Wheaton campus, the Old Colony Correctional Center in Bridgewater, Mass., is only a 17.2-mile drive south on Interstate 495. But the short van ride each week during the fall semester transported students a world away.

There, eight Wheaton students took the shared sociology and psychology course “Inside Out: Making Sense of Data” alongside 10 people incarcerated at the prison. The class was part of the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program that is designed to facilitate dialogue across differences, including social barriers.

The Inside-Out program, which is based at Temple University in Philadelphia, was founded in 1977 as a way to bring together “outside” campus-based students with “inside” incarcerated students for a semester-long course held in a prison, jail or other correctional settings, according to the website. It has since grown into an international network of trained faculty, students, alumni, think tanks, higher education and correctional administrators and other stakeholders who are committed to social justice issues.

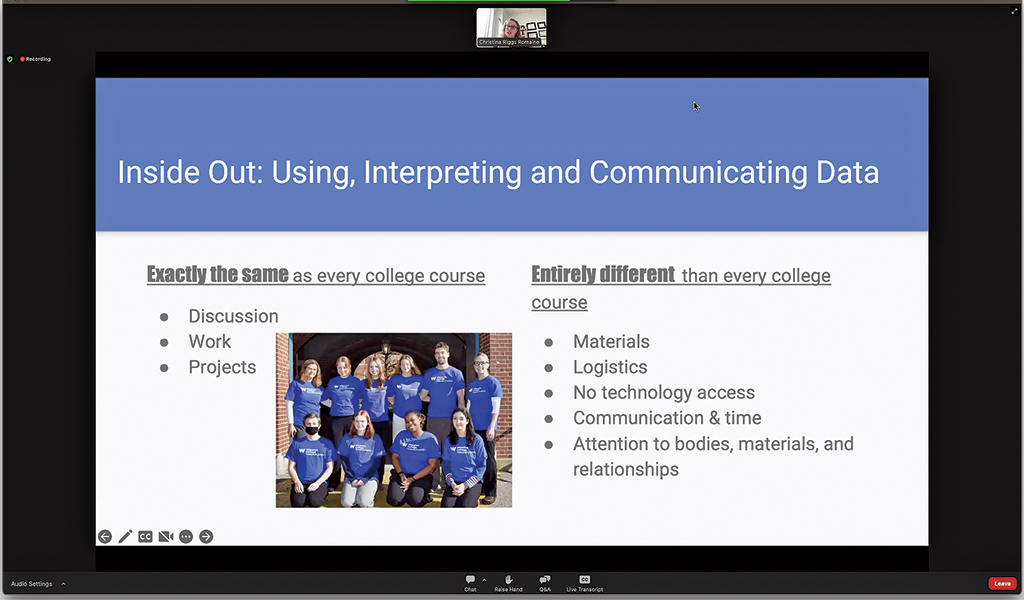

After intensive training from the Inside-Out Center, Wheaton Professor of Sociology and Associate Provost Karen McCormack and Associate Professor of Psychology Christina Riggs Romaine worked in partnership with the Massachusetts Department of Corrections and collaboratively taught the 10-week course in a classroom inside the medium-security facility.

“Inside-Out was entirely different from any course I’ve ever taught in the way you had to structure it within the constraints in the physical space. I’ve never had to go through a metal detector to go to class before,” Riggs Romaine said. “And, yet, it was still a college class. It was still willing, curious people thinking together, reading interesting things, talking about them, having questions, laughing and good-naturedly arguing about things. And, so, it was exactly the same and entirely different, all at the same time.”

Both groups of students said they gained valuable knowledge about how to understand, analyze and use data and described the experience of interacting with each other as eye-opening and life-changing.

“I loved the idea of learning about using data to tell stories and the ways in which data can be misconstrued, but I was especially interested in the class because it was being taught in a prison, with students from inside the prison. … It was a space for learning from one another as equals, for seeing each other as people,” said Alex Blue ’23, who is pursuing an independent major in human services. “One of the most valuable lessons I learned is that we are so much more than our so-called ‘defining moments.’”

Old Colony Correctional Center students shared their thoughts in answers to reflection questions at the end of the course:

“As someone who was on a path to college—at one point in time—I missed out on that opportunity because I ended up in prison as soon as I graduated from high school. These courses give me a taste of what that experience would have been like. And that, of course, is priceless,” one student wrote.

Another said: “I learned to be humble because I made assumptions about the levels of experience the outside students had and I was humbled by the wealth of experience they had at such young ages and the wisdom they brought to each class.”

McCormack summarized a common theme. “When we gave them the last round of reflection questions and we said to the inside and outside students, what would you most like to know? What questions would you most like to ask each other? One of the questions almost every inside student asked is, ‘Do you see us differently now? Are you less scared of us now? Do you see us as more human?’” she said. “Clearly, I think our group of students didn’t go in with negative baggage, but the experience still changed their way of thinking.”

Riggs Romaine and McCormack, who on April 5 presented the virtual faculty lunch talk “Learning Behind the Prison Walls” about the program, said they hope more Wheaton students get to experience an Inside-Out course in the future.

“We see how it could be so integral to learning experiences. … Bryan Stevenson is an attorney who works a lot with wrongful convictions and folks on death row. One of the big things he always talks about is if we’re going to bring about justice and bring about effective change, we have to get ‘proximal,’” Riggs Romaine said. “This class puts students proximal to [the Old Colony students]. I think that matters from a social justice lens. It gives our students a whole set of skills, knowledge, capacity and awareness to be involved in those systems. Whether it is because they believe and support them, want to change them or dismantle them, it’s just going to give them this perspective that you can’t have unless you’ve been there.”

Opening doors

Off of a quiet woodsy road, the Old Colony Correctional Center sprawls out with multiple buildings and fencing trimmed in razor wire. A sign that greets visitors immediately starts spelling out restrictions: No photos allowed.

The protocols and procedures to get into the building where the Inside-Out course was held were even more stringent. Every single visit required a rapid COVID-19 test onsite. No cell phones, laptops or other electronics were allowed. Shoes were removed and placed in bins. Each person was asked to show the backs and palms of their hands and run them along their waistbands and open their mouths before walking through a metal detector.

The process was nerve-wracking the first few times, but eventually became routine.

“The one thing that never got less intimidating were the big, loud metal doors,” said Isabella Robishaw ’23, a psychology major who plans to earn a master’s degree in social work. However, she and the other Wheaton students and the professors said it was well worth the effort.

McCormack and Riggs Romaine chose to teach this particular class because it provides useful skills for all students as they leave Wheaton or Old Colony and enter the workforce. In the course, students together explored social science data, learned how to make sense of patterns that emerge from quantitative and qualitative data, practiced interpreting them and then communicated their research findings in final collaborative projects.

“We prepared a packet of data prior to the start of the semester that focused on workforce participation, unemployment, areas of job growth, recruiting and networking [how people find jobs], and wages and salaries,” McCormack said. “We included data from the Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics and from research studies. The data were all employment-related but did cover different topics because we wanted to give students some choice to form a question that was interesting to them.”

In addition to gaining skills in using data for storytelling and understanding issues, both groups of students made self-discoveries and connections as they experienced a new appreciation for the opportunity to learn.

“The willingness and desire to engage was so genuine and heartfelt, and that was really rewarding,” said McCormack. “I don’t think our Wheaton students walk into every classroom on campus thinking that they’re grateful to be there, but I think every student walked into the Old Colony classroom feeling like they were grateful to be there.”

Riggs Romaine agreed: “The one thing I really noticed for the Wheaton students was as we walked out that first day, one of them made a comment like, ‘I don’t always think about it as a privilege to go to college, and I’m realizing it is.’ … The Old Colony students were very aware of the privilege of education, and so they were showing up and ready.”

Riggs Romaine had been thinking about the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program since she first learned of it from a colleague at a conference before she started teaching at Wheaton. She ran into McCormack in the hallway in Knapton shortly after joining the faculty and began chatting about the program. The two agreed that it would be great to pursue.

Riggs Romaine is a clinical psychologist whose scholarship focuses on juvenile competency and determining the best policies and practices for fair treatment within the juvenile justice system. Her clinical work and research have taken her in and out of many correctional facilities during her career.

“We know the power of education. So, the chance to bring a college liberal arts approach to education to the folks who are on the inside was a huge piece of what attracted me to the program from a social justice lens,” said Riggs Romaine.

McCormack’s work explores the intersections of inequality, community and technology and she, along with Riggs Romaine, is a member of the team that developed Wheaton’s new major—criminal justice, restorative justice, and criminology.

“I teach a lot about inequality focused on the intersections of class, race and gender,” said McCormack. “This class offered the opportunity to explore some of those issues in relation to the data on employment and the workforce. Students’ life experiences shape their approach to these data and navigating discussions of these powerful social forces required all students to listen thoughtfully and learn from one another.”

In 2019, the professors went through a weeklong instructor training facilitated by the Inside-Out Exchange Prison Program at the Stateville Correctional Center, a maximum-security prison for men in Crest Hill, Ill.

They had planned to launch the Inside-Out class at Wheaton in the fall of 2020, but COVID-19 derailed that until this academic year.

Teaching and learning were radically different under the Department of Corrections protocols and within the physical space (a long narrow room). The absence of any electronics in the space was challenging but also refreshing, the professors said.

“The level of attention and how you use your time is just very, very different. So, when we were in that space, we were all completely in that space together,” McCormack said. “It felt a little bit nerve-wracking as we were planning because you had to think, ‘OK, there are no slides.’ It turned out that we could move paper in and out more easily than we thought we would be able to. So, we did end up making worksheets.”

Riggs Romaine said she definitely appreciated the focus the lack of technology allowed.

“In a class on data, we would send students to find data and look on the internet or go into a database or use databases that the college has, right? All those tools were not available, but what we got were students who were 100 percent present, in the moment and not distracted by technology,” Riggs Romaine said.

And both groups of students thrived.

“Some of our happiest moments occurred when we’d look at each other in the classroom and they were working on their projects and you’d hear them arguing about whose ideas should take precedence, and it was like, this is exactly what you want to hear in a college class,” McCormack said.

Acquired knowledge and trust

Jennifer Hodel ’23, a psychology major, said she developed new skills in working collaboratively on a project in which Wheaton students could not communicate with their inside classmates outside of the correctional facility.

“We had to be flexible and productive given the time we did have together,” said Hodel, who plans to attend graduate school to become a school counselor and a licensed professional clinical counselor. “I learned so much from each and every person in this class and feel that this experience helped me not only grow in terms of learning to interpret, analyze and communicate with data but also in general as a person.”

Patrick Kelley ’23, a sociology major, said the constraints of the collaborative group work provided lessons that will be valuable long after Wheaton. He hopes to work in probationary services to assist formerly incarcerated individuals with their transition back into society.

“In order to be the most effective in group work, it is essential to trust your peers. Because the provisions of this class did not allow us to work with our group members outside of class, we had to trust that our group mates would do their work,” Kelley said.

And all did.

“Every group managed to do an excellent job, and I think a large piece of that was because of the passion each of us had for the class,” said Blue, who hopes to go into social work or become a clinical psychologist. “With all of our dedication and hard work, we overcame the barriers to collaboration relatively easily [though there were still some hiccups].”

Invaluable affirmation and connection

Laureen Doolan, who directs education at the Old Colony Correctional Center and was Wheaton’s partner throughout the program, said that the course was as important for the Old Colony students as it was for the Wheaton students because it provided validation of their skills.

“Many of the inside students received a high school equivalency diploma while incarcerated because they failed out of traditional schools. They often lack confidence in their academic abilities. The concept of allowing them to participate in a college-level class demonstrates to them that they are not only capable, but that they can excel,” Doolan said.

“Participation in a class alongside outside students also allows them to see that there are commonalities in themselves and these students and that the traditional students may also share in their insecurities about the ability to do well in college,” she said. “This program is important for the traditional students as well because it provides them with the opportunity to see the incarcerated as people who have made mistakes in their lives and to not define them by their crimes.”

The closing ceremony

On a rainy Dec. 7, 2022, Wheaton students and professors took one last van ride to Old Colony for a closing ceremony and class wrap-up session. Invited guests Provost Touba Ghadessi, Vice President of Student Affairs Darnell Parker and the Wheaton magazine editor also were in attendance with Massachusetts Department of Corrections representatives.

In a cavernous visiting room, students and the professors (as well as guests) took turns expressing gratitude and mutual appreciation, acknowledging bravery and joking.

“You’re not looking down your noses at us. … You made us feel like we were in college with you and I want to thank you for that,” said one Old Colony student, reading from pages of his prepared remarks.

Anda Brown ’24, an independent major in quantitative criminology, told the group: “My time with all of you has been really impactful. This is a class I will talk about and remember for the rest of my life.”

And Provost Ghadessi offered: “Knowledge is something like love that stays with you forever the more you share it. This class has allowed us to grow that knowledge. Thank you to all of you.”

After the remarks, students walked to the front of the room one at a time to receive a certificate.

“I almost cried during the closing ceremony,” Blue said. “Everyone gave beautiful speeches, and it was very bittersweet because we were celebrating the time we spent together, and we were also melancholy because we could never see each other again.”

Robishaw expressed a similar sentiment. “Everyone seemed so proud of what they had accomplished during the class, but it was also clear that people, including me, were sad it was coming to an end,” she said. “The speeches given by some of the students did a great job summing up what we learned regarding data and statistics and how to apply that to real-world issues. The students’ speeches also demonstrated how meaningful and enjoyable this class was for both groups of students.”