Fish tales

Scientists already know that potassium plays an important role in the body, affecting kidney function, nerve signal transmission and heart rate. But could it signal our bones when to stop growing?

Assistant Professor of Biology Jenny Lanni has been testing that hypothesis for more than two years with the help of student researchers and one thousand zebrafish.

Her research, which builds off postdoctoral work she began in the laboratory of Dr. Matthew Harris in the Orthopedics Department at Boston Children’s Hospital, has potential applications in human medicine, as zebrafish share about 60 percent of their genes with humans.

“Using whole genome sequencing, I found that zebrafish with extra-long fins carry a mutation in the KCC4a gene,” Lanni said. “This mutation seems to increase the amount of potassium that cells transport across their membranes.”

Determining the mechanism that connects potassium levels to fin size is the focus of Professor Lanni’s research at Wheaton.

Fishing for answers

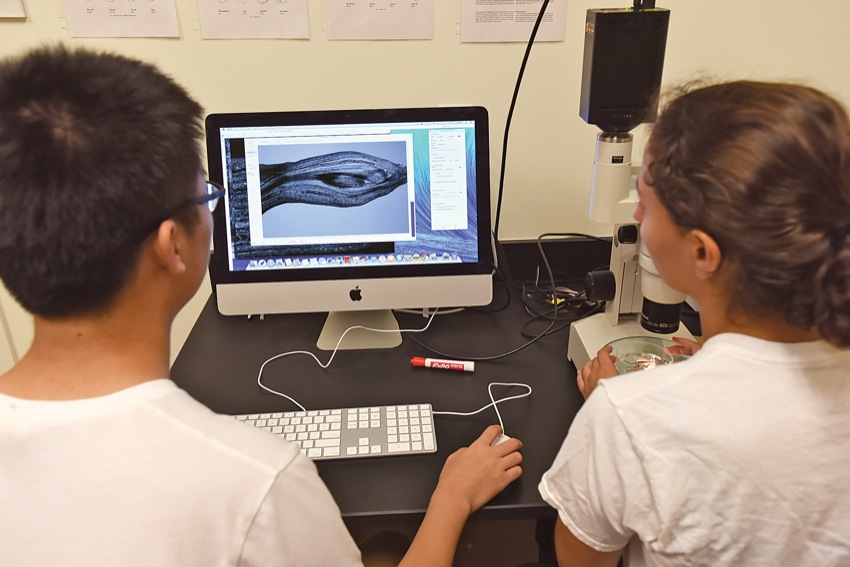

To conduct her research, Lanni works with lots of zebrafish—both the long-finned mutant strain and the regular short-finned strain, also called “wildtype.” Both have been genetically modified so their blood vessels are fluorescent, making them easier to see and photograph under a microscope. The fish are housed in a state-of-the-art aquaculture facility in the Mars Center for Science and Technology. The facility was established with funding from the Provost’s Office and is maintained by Animal Facilities Supervisor Amanda Bettle ’06.

Lanni and her student assistants are attempting to prove that a mutation in the KCC4a gene is responsible for the mutant strain’s long fins by injecting small amounts of DNA into one-cell zebrafish embryos under a microscope.

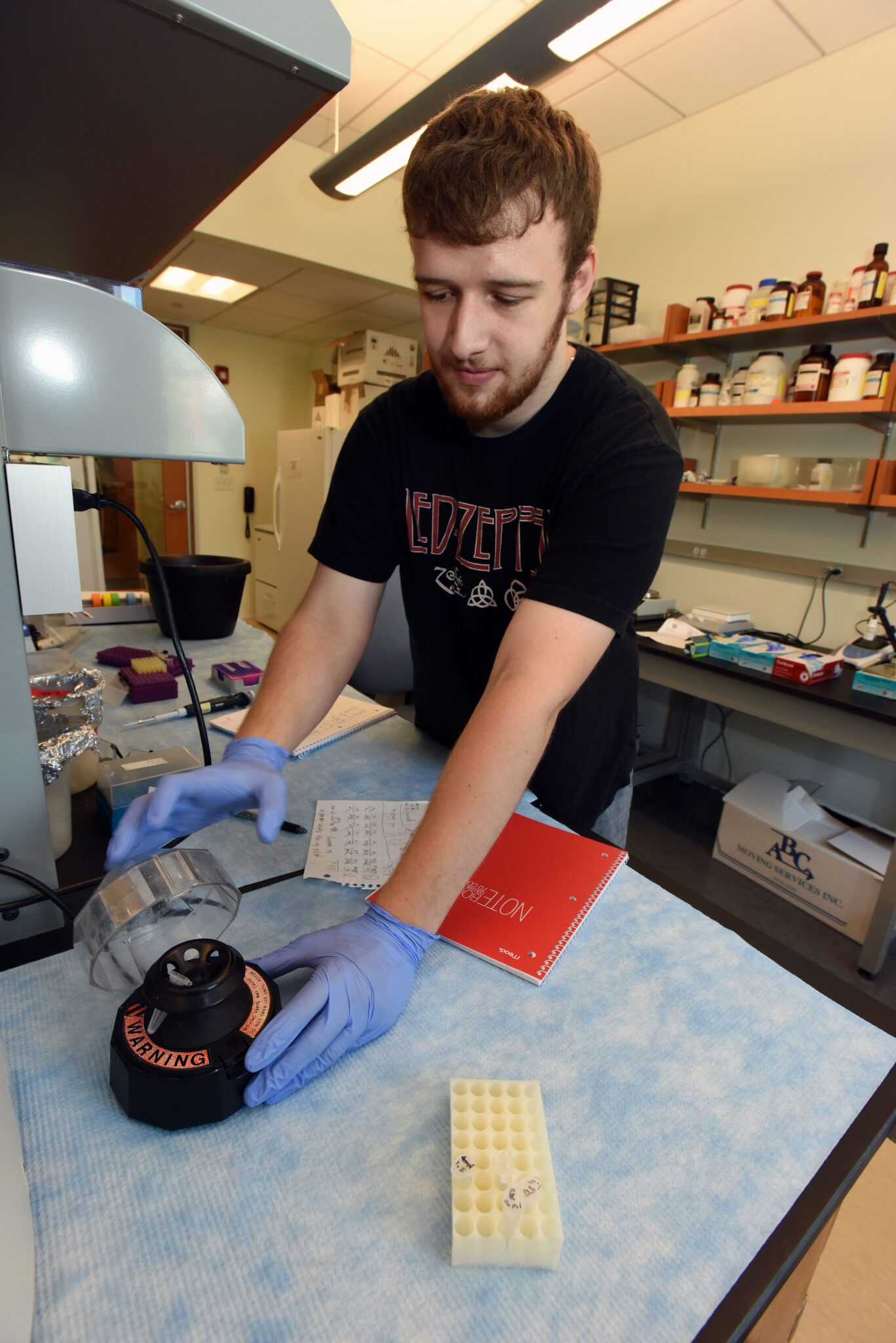

Ethan FitzGerald ’16, a double major in biochemistry and political science, is introducing an activated version of the KCC4a gene into wildtype zebrafish to see if it will cause long fins when the injected embryos are raised to maturity. Kathryn “Katie” Henrikson ’16, a double major in biology and psychology, is using gene-editing technology to inactivate the KCC4a gene in the long-finned strain, to see if this will prevent fin overgrowth.

“Ethan and Katie have both mastered the microinjection procedure, as well as learned molecular biology techniques needed to prepare the DNA for injection and to analyze DNA samples from injected embryos,” Lanni said.

They hope to have initial results from the two experiments this spring.

Henrikson said she is excited to use the cutting-edge gene-editing technology, which is known as CRISPR/Cas and has received widespread media attention.

“This method has never been used at Wheaton before, and I am really hoping that the results from the project will help Professor Lanni with future research,” she said.

Another area of Lanni’s research is exploring why zebrafish that carry two copies of the KCC4a gene mutation (homozygotes) have less vigor as adults than those that carry just one copy of the mutation (heterozygotes).

“Work by my students last summer revealed that the blood vessels in the fins of heterozygous fish are larger and more interconnected than those of normal fish,” Lanni said. “Ethan will be studying the fins of homozygous fish to see if this vascular phenotype is increased, and if vascular problems elsewhere in the body might be contributing to their poor health.”

FitzGerald and Ao “Kevin” Shi ’17 are taking a closer look at heart function and nervous system development in the homozygous fish.

Building scientific skills

FitzGerald plans to pursue a career in science and is currently applying to graduate schools. He said his experience working with Professor Lanni has been invaluable.

“I want to become adept as a researcher, tackle scientific questions and generate research results that move the academic and human communities into a redefined 21st century age of science,” he said.

Shi, a biochemistry major from China, has been assisting Lanni for nearly a year and said he has enjoyed focusing on the biology side of his major, as well as learning about the differences between Chinese and American scientific research.

“This training is different from most of the Chinese education system for science students, which is the reason that I chose to study in the United States,” Shi said. “I have learned lots of experimental techniques as well as data analysis skills.”

Biochemistry major Caroline Stanclift ’16 is assisting Lanni with a related area of research—figuring out in which tissues the KCC4a protein is expressed.

“The hope is that by finding out where the protein is expressed, we may gain some insight into its mechanism in fin growth,” Lanni said.

Stanclift said she loves many aspects of the work, but mainly the way Lanni balances mentorship in the lab with letting her students work out their experiments independently.

“I’ve leaned critical biochemical techniques but also, more important, how to communicate questions clearly, when to offer my ideas and work with my fellow lab mates,” Stanclift said.

As for Lanni, working closely with student researchers helps keep her focused and energized about her research.

“Unlike in most laboratory classes, I truly don’t know what results they are going to see. Together we think about the right controls to include for a valid experiment, choose what protocol to try, and discuss how to trouble shoot problems when things don’t work at the bench,” she said. “This is a realistic introduction to scientific research, in which they learn that science requires creativity, perseverance and patience. Fortunately for me, my students possess all of these qualities in abundance. ”