Fighting cancer with innovation

Nancy Klauber DeMore ’87 is an accomplished doctor, cancer researcher

Solutions often come to mind when you least expect them, or sometimes when you aren’t even looking.

Solutions often come to mind when you least expect them, or sometimes when you aren’t even looking.

Dr. Nancy Klauber DeMore ’87, medical director of the Breast Center and surgical oncologist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, S.C., understands that well.

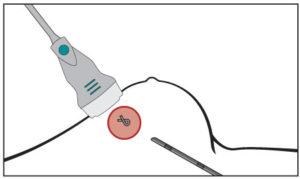

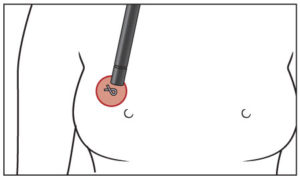

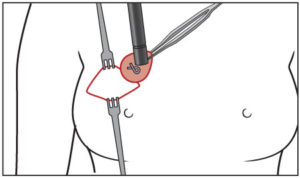

The doctor performs about 200 lumpectomies per year—which require breast cancer patients to undergo two invasive procedures: the insertion of a wire to locate a titanium clip (which is first put in to pinpoint the position of the tumor) and the surgical removal of breast tissue around the wire.

Many times during the past 15 years, DeMore has listened to complaints from patients about the inconvenience and discomfort of the two separate operations.

The procedure to locate the titanium clip must take place in the radiology department, which is often not next to the operating room—and sometimes requires driving to a different building. Also, patients describe it as scary and painful, and if difficulties with the wire insertion occur, delays in accessing the operating room cost both time and money. Even a 30-minute delay can cost thousands of dollars, she said.

See illustration: Gentler treatment

“I didn’t set out trying to find a solution to this problem. The idea came to me while operating. I thought, ‘What if we could detect the titanium clip noninvasively with a metal detector?’ The words came out of my mouth,” DeMore said, adding, “It would simplify a lumpectomy into a one-hour procedure.”

With her revelation, DeMore formed a partnership with bioengineers at Clemson University, in South Carolina, to develop a working prototype of a hand-held metal detector sensitive enough to detect titanium. The prototype has won awards and interest from medical device companies and surgeon groups. DeMore has filed for a patent and will be working toward FDA approval. She hopes it will be available on the market within three years.

“Nancy really has pushed the project forward from the start,” said Delphine Dean, a collaborator from Clemson University, who serves as associate professor of bioengineering. “She believes in the impact that this idea could have for patients and it really shows when you talk to her.”

Journey to medicine

DeMore did not originally intend to pursue a career in medicine.

As a new Wheaton student, she had her heart set on becoming a marine

biologist. During high school, she worked for four summers in an aquarium on Cape Cod, and loved the underwater critters she encountered.

But two things happened that DeMore did not expect: she was prone to seasickness, and she met professors who inspired her to pursue cancer research, specifically tumor angiogenesis—the process by which a tumor attracts blood vessels to nourish itself and grow.

“My father was a doctor, and I spent time in his office since I was 10, but I hadn’t decided on a career in medicine,” she said. “It didn’t come together until college. I knew then I wanted to become a physician scientist.”

DeMore enjoyed courses with Professor of Biology Emerita Barbara Brennessel. But DeMore found her calling when researching tumor angiogenesis as part of her honors thesis, which she conducted with her advisor, Professor of Biology Edmund Tong.

Realizing her love for research, her junior year she toured a lab of Dr. Judah Folkman, a researcher at Harvard Medical School who was widely known as a pioneer in the study of cancer angiogenesis. She had devoured all of Folkman’s research papers.

When DeMore asked Folkman how to secure a position in his lab, he advised her to go to medical school and apply for a research fellowship during her residency. Folkman told her to apply two years early because as many as 200 applicants vie for the position in his lab.

And after graduating from Wheaton with a bachelor’s degree in biology, she followed his advice. She went to University of Health Sciences, Chicago Medical School, where she was awarded her M.D. (and fell in love with surgery). As soon as she matched at the Boston University Medical Center for her five-year General Surgery residency, she applied for the fellowship in Folkman’s lab—which she successfully secured.

She spent three years in the fellowship at Harvard Medical School with Folkman, who passed away in 2008.

“Those were the best scientific years of my life. I learned an enormous amount about tumor angiogenesis,” she said. Following that fellowship, she completed a surgical oncology fellowship at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, before taking the position of professor of surgery at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, a role she held for 13 years.

Balancing practice and research

As DeMore developed into a leading surgical oncologist, she balanced two passions: a fondness for research, and helping patients, notably women, with cancer treatment.

At Wheaton, through her liberal arts coursework, she gained an appreciation for gender studies, she said. “Focusing on breast cancer and women’s health is a natural extension of that. After residency in the cancer center, I knew I wanted to focus on breast cancer. I enjoy the patients. They are just very appreciative.”

In addition to clinical care, DeMore has immersed herself in cancer research—in particular, drug development.

For more than 25 years, she has continued her investigation into tumor angiogenesis—research that she first began as a Wheaton undergrad.

In 2009, she co-founded Enci Therapeutics, Inc., a biotech startup company that is developing a monoclonal antibody therapy for cancer patients. (Monoclonal antibodies are made by identical immune cells that are clones of a unique parent cell.)

Specifically, her work involves discovering novel factors that stimulate tumor growth and developing new drugs that block these factors, therefore inhibiting additional growth. For some patients, popular drug therapies don’t work, thus her research is intended to introduce new promising pharmaceuticals to improve their long-term prognosis.

Overall, DeMore has been a co-investigator on 11 active clinical trials and 24 completed clinical trials. In addition, she was appointed to a six-year term on a National Institutes of Health committee focused on cancer immunopathology and immunotherapy.

Her work has led to clinical advances in the care of breast cancer patients, in particular those with metastatic breast cancer.

DeMore’s recent work on developing a titanium metal detector to simplify lumpectomies is just one part of her larger effort to improve clinical care, and treatment, in cancer patients.

Detecting better treatment

At Medical University of South Carolina —which she joined in October 2014—DeMore serves as professor of surgery, BMW endowed chair for cancer research, medical director of Medical University of South Carolina Breast Center, and program director of the M.D./Ph.D. training program.

As an endowed chair, DeMore is provided with funds and resources for research, she said. In her role, she splits her schedule between clinical care and research, with some time set aside for administrative duties and education.

Working with patients directly improves her ability to conduct meaningful research, she said. “You can do the best research in the world, but if it’s not clinically relevant, it’s not going to help someone.”

The development of a titanium metal detector to simplify lumpectomies offers a real benefit to lowering costs and making patients happier, she said.

After DeMore’s “aha” moment in the operating room, she formed a strong working partnership with students and faculty at Clemson to bring this invention from idea to fruition.

It began with a phone call to Dean, whom DeMore had met at an innovation symposium in Charleston, S.C. in 2015. “I explained the issue to her and asked if it would be possible to develop some type of metal detector that could detect titanium,” DeMore recalled.

Dean brought the problem to students in her bioinstrumentation class, and—in collaboration with DeMore—they joined forces to find answers.

“Nancy knows how to explain the issues and problems to folks from lots of disciplines, and it’s sometimes hard to communicate between engineers and medical people,” Dean said. “She also is open to ideas and viewpoints, which has allowed the project to change a bit and be more effective from earlier versions.”

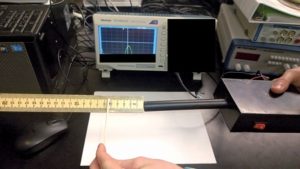

The students blended their expertise of engineering principles with DeMore’s knowledge of the medical environment. After the development of several versions, the collaborators eventually arrived at an initial prototype working as a proof of concept in the lab.

“Besides coming up with the first idea, Nancy is the one who has been pitching and getting the project moving beyond just a cute student project,” Dean said. “We got the initial prototype working, but there are many steps necessary between that and a viable product that can impact patient care. Nancy has been the one championing the project, getting the clinical perspective and support, and drumming up some seed funding to make the project successful.”

Their combined efforts have paid off. In August 2016, DeMore and Clemson colleagues filed for a patent on the detector. The hope is to obtain FDA approval and conduct clinical trials, and potentially for this product to be available for use on the market in the future, she said.

“If it works in the clinic, it really has the ability to revolutionize breast surgery,” DeMore said.

The prototype of the metal detector is gaining attention, and awards, among surgeons, innovators and other players in the medical industry.

DeMore presented the innovation at the Charleston Southeast Medical Device Association Pitch Rounds competition—an event sponsored by MUSC and the Foundation for Research and Development in April 2017, and won first place.

Also, the invention impressed members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. DeMore presented the metal detector at the association’s annual cancer symposium in Seattle in March, and it was awarded first place in the “Innovations in the Operating Room” competition.

In the meantime, her work to improve clinical care and treatment as a doctor and researcher is far from over.

“Nancy is truly a clinician-inventor,” Dean said. “She is very innovative and comes up with great ideas that are grounded in clinical needs. This is just the beginning.”