Examining the ‘Great Resignation’

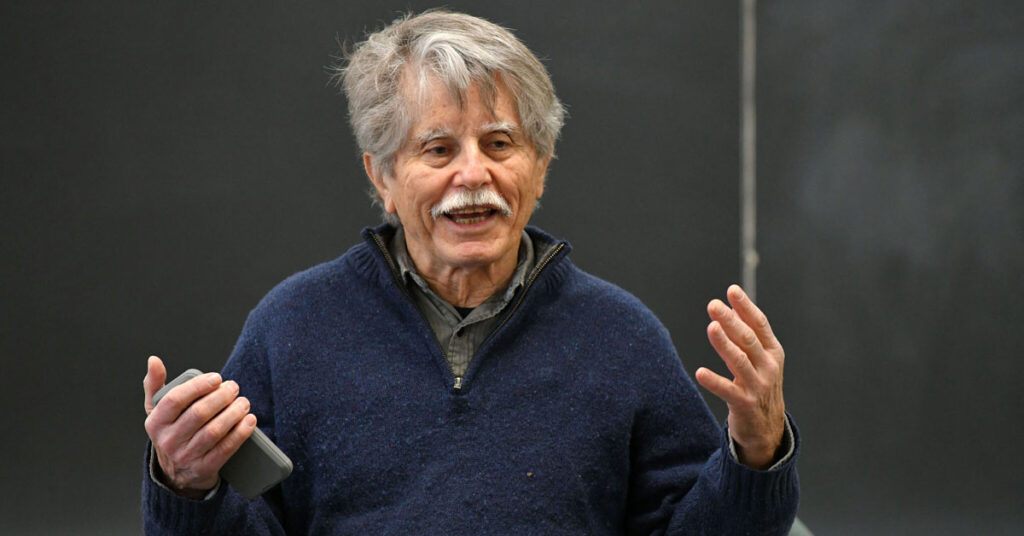

Professor of Economics John Miller shares insight on workers quitting their jobs

Professor of Economics John Miller shares insight on workers quitting their jobs

“My students undoubtedly already knew that a college degree gives them a leg up in the labor market. But I don’t think they appreciated just how much of an advantage it provides in the pandemic and post-pandemic economy. …The ‘Great Resignation’ is a compelling example of how changes in the macroeconomy shape the opportunities and life-chances of my students as well as those of workers of all stripes.”

During the pandemic, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported a major uptick in workers leaving their jobs. Intrigued about why, how and the implications, Wheaton magazine editor Sandy Coleman wanted to know more from the perspective of Professor of Economics John Miller. For more than two decades, Professor Miller has been a contributing editor to Dollars & Sense, a popular economics magazine based in Boston, and during the spring semester he is teaching “Macroeconomic Theory” at Wheaton College.

Tell us about the course you are teaching this semester.

“I have the most to say about the ‘Great Resignation’ in my ‘Macroeconomic Theory’ course. The students begin the semester by grading the performance of the U.S. economy since the pandemic-induced economic shutdown in March 2020. They examine several key economic variables in Economic Indicators, a compendium of economic data and charts published monthly by the Council of Economic Advisors. I’m convinced that knowing something about the current state of the macroeconomy is a prerequisite for learning theories. Employment growth and unemployment rates are always two of those key variables. It is in that context that we discuss the ‘Great Resignation.’”

Describe the ‘Great Resignation’ from your point of view as an economics professor.

“‘Resignations’ is not a term economists use. What economists track is ‘quits,’ employees who leave their jobs voluntarily. Quits increased rapidly with the economic recovery from the pandemic recession, reaching 4.5 million in November 2021, the highest level on record.

Economists do use the term great, as in the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009, and the Great Depression of the 1930s. Calling today’s record level of quits the ‘Great Resignation,’ however, is most likely an exaggeration. Historical evidence suggests that quit rates were higher than the current record rates in 1945 at the close of World War II and likely higher in the late 1990s during the dot-com bubble.”

Why is this happening now?

“The fact that resignations are rising is hardly surprising. During every economic upswing the number of jobs multiplies, and more workers quit their current job in hope of getting a better one. Nor is it surprising that quits would reach record highs in the current recovery. This recovery has added back lost jobs close to three times as quickly as the longest sluggish recovery from the Great Recession during the last decade.”

How is the “Great Resignation” impacting the economy?

“Great or not, surprising or expected, today’s resignations have had a profound impact on the economy. Workers hold on to their jobs for dear life in an economic downturn. Quits only rise when the economy expands, creating more jobs and making it easier for workers to find another job.

There is good evidence that by and large workers are quitting their jobs, not work. What we know is that hires are greater than quits in all sectors of the economy. So, it seems that workers who quit their jobs are likely taking jobs in the same sector. We also know that last year job switchers got bigger raises than workers who stay put.

For employers, higher quit rates increase their turnover costs, the money they need to spend to recruit workers and train new hires. As the economy creates more jobs and the number of workers per job opening declines, employers also need to raise wages to attract workers. Still, despite those cost pressures, profits before taxes rose 10 times as quickly as labor costs from October 2020 to October 2021.”

Do you think these impacts are positive?

“Yes, and most definitely for low-wage workers. In the leisure and hospitality sector, where workers quit their jobs twice as often as workers in other sectors of the economy, worker compensation [wages and benefits] rose 6.9 percent during the last year, well above the 4.1 percent average for all private sector workers. This is especially important in the U.S. economy. Low-wage workers [workers who make less than two-thirds of median earnings] are nearly a quarter of our workforce [23.8 percent], a much larger share than the 13.9 percent average for advanced economies.

In addition, the Harvard Business Review is now dispensing advice to employers on how best to ‘develop tailored retention programs’ to address their higher resignation rates. That’s another good development.

The ‘Great Resignation’ has troubling aspects as well. Women’s quit rates are higher than those of men. In January, women’s quit rate was 4.1 percent, considerably higher than the 3.4 percent quit rate for men, according to Gusto, the payroll and benefits company. Even more troubling, the gender difference in quit rates was largest in the states with the highest incidence of daycare and school closings. These data make clear that employers who offer more fulsome childcare benefits and more flexible work arrangements are more likely to retain women workers than other employers.

Another quite troubling aspect of the resignation wave is the rapid increase in the number of health care workers quitting their jobs. With the health care system groaning under the weight of the pandemic, and their workloads increasing, 2.6 percent of health care workers quit their jobs in 2021. That was just about the economy average, but far higher than their 2 percent rate in 2019, and double their quit rate in 2010.”

What is the takeaway for workers?

“The ‘Great Resignation’ is a moment when workers are evaluating their jobs. The large number of layoffs during the pandemic shutdown gave workers time to reflect on their work life. And the rising number of job openings provides them with an opportunity to switch jobs if that’s what their gut told them to do. On his blog, economist Paul Krugman even asked, ‘Is the Great Resignation a great rethink?’”

What do you hope your students can learn?

“My students undoubtedly already knew that a college degree gives them a leg up in the labor market. But I don’t think they appreciated just how much of an advantage it provides in the pandemic and post-pandemic economy. The Monthly Labor Review found that during the pandemic shutdown, 67.5 percent of workers with a college degree could do their jobs from home, while that was true for just 24.5 percent of workers with only a high school diploma.

Beyond that, the ‘Great Resignation’ is a compelling example of how changes in the macroeconomy shape the opportunities and life-chances of my students as well as those of workers of all stripes.”