Driving innovation

Industrial designer Alex Bandazian ’09 reimagines the automobile

When most of us step into a car, we simply start the engine, shift into drive and steer the vehicle to our destination.

Alex Bandazian ’09, a senior industrial engineer, experiences cars and driving through a much more nuanced perspective.

“When getting into a car, certain things jump out at me: the silhouette and the body lines, the face, including the headlight and grille, and the feeling and sound of the door as it shuts,” he said. “I notice any subtle delighters, like the material on the armrest, or the texture on a volume knob. Even the way I navigate through a vehicle’s infotainment system can leave an impression.”

In the role of industrial designer, Bandazian works with clients to develop a product’s aesthetics, including its overall shape, colors, textures and sounds, as well as usability. He harnesses specific skills, including traditional and digital sketching, computer-aided design and modeling, to create prototypes.

Now, he is working on an ultimate design job: developing prototypes of a new kind of automobile.

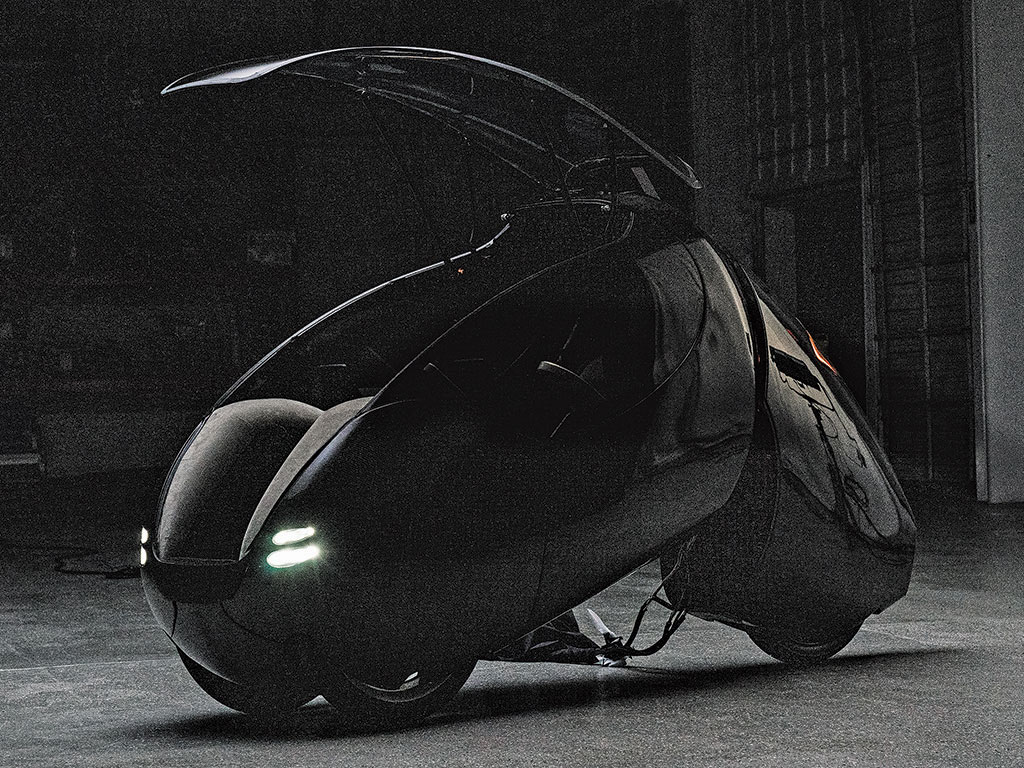

As an industrial designer at Indigo Technologies, a Cambridge-based startup, he is creating the look, feel and functionality of a super-efficient electric vehicle, using the company’s patented technology, which aims to one day fundamentally change how cars are made.

“I joined Indigo because I wanted to put my time and energy into designing something that would have a real impact on the world and bring value to people’s lives,” Bandazian said. “We need consumer-focused design to tackle big problems now more than ever, and I feel incredibly lucky for the opportunity to get to bring that perspective to a company like Indigo that understands and values that.”

A drive to design

Bandazian, who graduated from Wheaton with a bachelor’s degree in English and a minor in studio art, has designed in all types of work environments—developing surgical instruments for spine procedures, food storage containers, consumer electronics and more.

In 2017, he joined Indigo Technologies, a company founded by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor and investor Ian Hunter to explore storing and using energy in different ways—with the ultimate goal of reducing pollution and waste in automotive technologies.

In April 2019, the company unveiled its Traction T1 Propulsion System, which seeks to replace traditional car parts—such as engines, drive shafts, axles and brake lines—by moving the critical vehicle function into the wheel. (The technical term is an in-wheel active suspension system.) This would allow for the manufacture of smaller, lighter and more aerodynamic vehicles.

The startup’s mission of improving vehicles and reducing reliance on fossil fuels attracted Bandazian to the position, he said.

“The current transportation paradigm has existed for roughly a century without a lot of truly disruptive innovation,” he said. “Faced with the looming threat of climate catastrophe, I think we have no choice but to do what humans have always done in times of crisis: innovate.”

At Indigo, Bandazian is working mainly on electric vehicle prototypes for the Traction T1 Propulsion System, which the company has developed over the past decade.

“Because the technology we’re working on will be integral to the vehicles of the future, in a sense we need to build those vehicles now to really understand the space, and also communicate our vision,” he explained.

Depending on the week, Bandazian might be sketching concepts for new vehicles, using software to design components, conducting user research, fabricating prototypes or working on presentations for

potential partners.

When visualizing a concept vehicle, he uses a combination of hand sketching (old-fashioned pencil and paper) and digital sketching to think through complicated problems, experiment with form and materials and story-board user interactions, he said.

“Digital sketching is one of the fundamental skills of the industrial designer. It’s one of the fastest and most effective ways to get the ideas out of our heads and into the real world so that we can talk about them, get feedback and iterate quickly,” he said

Grant Kristofek, director of design at Indigo Technologies, collaborates closely with Bandazian on a wide range of projects. He said Bandazian’s work has been instrumental in translating how the technology will work and operate in the real world.

“Alex is energetic, empathetic and creative and maintains a fun, optimistic and humble approach to design. He has a great deal of natural talent, which he cultivates by continually developing his digital and hands-on modeling and design capabilities,” Kristofek said.

Bandazian said he enjoys being immersed in every part of the process.

“I love that I’ve been able, in a very short amount of time, to have so many different experiences and work on so many different aspects of the design. I feel like I’m constantly learning and expanding my tool kit, and I find that incredibly rewarding,” he said.

Fueling a passion

Bandazian’s passion for industrial design originated from the maker movement, which focuses on technology-inspired do-it-yourself projects, as well as electronics, robotics, 3D printing and traditional arts and crafts.

Both of his parents are makers. “My dad was always working on the house or building furniture in his woodshop and my mom worked as a textile restoration expert,” Bandazian said.

He grew up surrounded by vats of wool soaking in natural dyes, helping his father with woodworking projects on the weekends, and every Halloween, he would sew his own costumes from McCall’s patterns.

During his youth, Bandazian took classes and participated in the open studios program at the Currier Museum school in Manchester, N.H. He also was active in his middle school’s Technology Student Association and enjoyed LEGO robotics and building and racing balsa-wood airplanes and miniature racing cars.

“By high school, I was becoming a consummate maker myself, and dabbled in just about every hobby you could think of, from painting miniatures to building catapults,” he said.

When he entered Wheaton, Bandazian felt drawn to many passions. He ultimately decided to major in English with a concentration in creative writing and minored in studio art.

“I always felt like I was pulled in a lot of different directions, an impulse that was definitely nurtured by Wheaton, and has been a consistent theme in my life,” he said. “I am a really curious person. In addition to writing and art, I was able to study philosophy, anthropology, political science, history, art history, law—and study abroad in Berlin. All of this laid a great foundation of critical thinking and analysis that would become really important, not only in my career but also in my development as a person.”

In the realm of writing, he was awarded a Wheaton Research Partnership grant his senior year that allowed Professor of English Lisa Lebduska to hire him to research the effect of the G.I. Bill on the teaching of writing in U.S. colleges. Bandazian spent a year researching articles and materials, including

congressional debates and speeches, addressing the enormous increase in enrollment caused by the G.I. Bill.

“Alex managed to be expansive in his approach, but didn’t lose focus. He had a genuine curiosity, a wonderful, self-aware sense of humor and enthusiasm for research. His writing was precise and lyrical,” the professor recalled.

Bandazian also spent much of his spare time at Wheaton building and fixing things for fun, including electronics and musical instruments. His senior year, he dug up a piece of railroad track in the woods behind the Outdoors House on Taunton Avenue in Norton, Mass., and built a makeshift anvil for backyard blacksmithing. (His first position after college was as an apprentice blacksmith at Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Mass.)

Also, his senior year, as part of his independent study with then-Professor of Art Tim Cunard, he built the sculpture “Suit and Desk” outside the Mars Arts and Humanities building. The whimsical upside-down figure remains on campus and can be seen just outside the window of the first-floor gallery.

A few years after Wheaton, Bandazian discovered industrial design, a field that complements his maker background. He completed the three-year industrial design certificate program from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt). During his final year, he won the Industrial Designers Society of America Merit Award for MassArt. He represented MassArt at the regional conference in 2015, where he took second place.

Before joining Indigo Technologies, he worked a number of jobs in industrial design, including on the innovation team at SpineFrontier, a medical manufacturer in Malden, Mass. There, he partnered directly with surgeons developing new surgical technologies and methods of operating that sought to be less invasive, with less blood loss and with better patient recovery time.

Making space for others

In addition to his work designing the vehicle of the future at Indigo Technologies, Bandazian still finds time to share his talent with other aspiring makers.

Since 2015, he has volunteered at the makerspace Artisan’s Asylum in Somerville, Mass. There, he offers industrial design consultations to help makers, artists and entrepreneurs take their ideas from concept to product, and he teaches workshops on design thinking.

“I really enjoy interfacing with that community and getting to see all of the

exciting things people are working on,

especially since a lot of the projects I’m involved with professionally have much

longer development cycles and strict regulatory environments,” he said. “It’s a great way for me to stay in touch with the parts of the design process that I don’t get to flex in my everyday life.”