50 years of inspiration

Professor Jay Goodman politically engages generations of students

In September 1965, with Lyndon B. Johnson as president and The Beatles topping the charts, a 25-year-old armed with a new Ph.D. from Brown University arrived on Wheaton’s campus to start teaching undergrads the fundamentals of American politics.

The young man’s name: Jay Goodman.

This fall found Barack Obama in LBJ’s place and Taylor Swift in the Fab Four’s. But Goodman was still in a Wheaton classroom—starting his 50th year of teaching at the college. And he seems as surprised as anyone by his own longevity.

“It’s shocking,” Goodman said—in his trademark deadpan—over coffee recently at the Starbucks near his home in Providence, R.I. “No one ever plans this kind of thing. It just happens.”

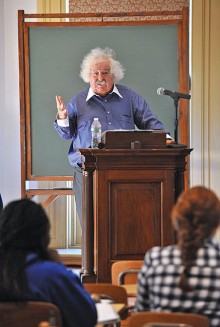

Planned or not, over the past half-century Goodman has become one of the most iconic and influential figures in Wheaton’s history. With his Einstein-esque shock of white hair and shuffling gait, today he is as much a part of the college as the Dimple or Peacock Pond. An oft-cited statistic estimates more than half of all living Wheaton alums have taken one of his classes.

“There’s something very special about his gift,” said Wyneva Johnson ’71, an assistant U.S. attorney in Washington and one of the huge number of former Goodman students who describe him as a mentor. “You can have stellar degrees, but there is a special gift when the student is just so inspired.”

“I walked into that great room in Mary Lyon where he held 101 and I felt like I’d found home,” said Mary Anne Marsh ’79, a prominent political strategist and pundit in Massachusetts who’s been close to Goodman for nearly 40 years.

“Just the room, the setting, his presence, his irreverence, his knowledge, his clear passion for politics in all of its forms—good, bad, ugly and glorious—I felt like I had found the place where I had always belonged,” she said. “It was just a transformational moment in my life that set me on this journey. … It really allowed me to picture what my life could be.”

“It was earth-shattering,” said Kathleen Jones Goldman ’92, an attorney at a top law firm in Pittsburgh. “He made all the difference to me, because I was never really academic before that, and he fired me up to get excited and do well.

“He would talk to me like I was already a lawyer,” she said. “He assumed it was already a fait accompli, so it never occurred to me it wasn’t going to be. That’s more than just saying to somebody ‘you can do it’ and being encouraging—that’s saying, ‘don’t even worry about it; you’re going to get this done.’ That was really a tremendous gift.”

Fred Marcks ’02 remembered how excited he would get when Goodman invited him to share a meal in the faculty dining room. “It felt special,” Marcks said. “I think I did all the talking, wanting to prove to him that I was worthy. The trick was on me. He had clearly already decided that was the case, but I was still working my tail off to ensure I didn’t disappoint him.”

Those comments and others like them are surely music to Goodman’s ears. When asked what he’s most proud of about his Wheaton career, his response was immediate: “The success of my students.”

The foundation

Jay Goodman was born in January 1940, shortly after the outbreak of World War II, into a middle-class family in St. Louis, Mo. His mother, a Louisiana native, had graduated from law school in 1933—a rare achievement for a woman in those days—and for a time his parents had operated a private law practice together. But after Jay was born she gave up law, eventually becoming a second grade teacher, and his father joined his family’s sporting goods business.

Unsurprisingly, education was important to the Goodman family. While his parents weren’t directly involved in politics, they regularly discussed current events at home, and his latent interest in the subject was sparked when he arrived at Beloit College, a small liberal arts school on the southern border of Wisconsin, in the fall of 1957.

“I particularly loved the political science department,” he recalled. “They were activists. In my first year and a half there, Wisconsin was flipping from a state that had never voted Democratic to a state that was going Democratic. … I jumped into it big time at Beloit.”

Goodman quickly became active in the Young Democrats, which in those pre-social media days allowed him to get up-close access to rising political stars like senators William Proxmire and Gaylord Nelson, who sometimes spent a half-day on the Beloit campus as they campaigned. He was also on hand when Senator John F. Kennedy delivered a guest convocation speech at Beloit in the spring of 1959.

Goodman loved campaign work immediately. “I like the field aspects of it,” he said. “I like meeting people. I like talking about the issues. There was real work—you sent out brochures, you knocked on doors, you learned a lot.”

And his allegiance stood out on the Republican-leaning campus: A yearbook teasingly described him and a fellow Democrat as “radicals.”

Goodman was also inspired by the way Beloit’s professors engaged with their students, giving them significant personal attention and providing them with direction and encouragement. “That’s what a professor is supposed to do,” he said. “It’s very gratifying. It’s more like being a coach—the team wins, I win. Some of the things that happened to my students are more satisfying than anything that ever happened to me.”

The Beloit experience convinced Goodman to become a professor. He won a prestigious Woodrow Wilson Fellowship that paid for a year of graduate study at Stanford, and then he did his dissertation at Brown.

Building a department

Goodman and Wheaton came together in 1965 for largely practical reasons—the college needed a new professor, and he wanted a job near Rhode Island. He was one of only three faculty members in the government department when he joined it; within less than two years, he became department chair at the ripe old age of 26. He quickly expanded its size and ambition as interest in politics grew amid the tumult of the 1960s.

“He built that department,” said Professor of Political Science Emerita Darlene Boroviak, a fellow Beloit graduate whom Goodman hired in 1970. “Jay had a mandate from the president to construct what was at that time the government department and to build it, and he did. So Jay’s mark is very much on the department. There’s just no question about that.”

Goodman quickly made an impression; the spring 1968 edition of the Quarterly described him as “one of the most popular professors on the Wheaton College campus,” and he twice won the Faculty Appreciation Award. From the start, he always kept his focus on the students.

“I learned a lot about interacting with students [from him],” Boroviak said. “That’s what I wanted, being a faculty member, and Jay certainly was a good role model for that. His knack for learning student names and interacting with students—having lunch, having dinner with students, and really becoming a role model for students—was something that I internalized very much in terms of how to do my job.”

Marcks still vividly remembers Goodman’s unchanging classroom routine: “In walks Jay Goodman, straight up the center aisle with his legal binder to the lectern. Plops his stuff down. Walks to the window, pushing it open. Loosens his collar and tie. Removes his gold watch and places it on the lectern. And then the magic begins.”

A number of alums recalled a Goodman instruction to “come see me,” written in their blue exam books, as a turning point in their academic lives. “He had a plan for me that I didn’t quite have for myself at the onset,” said Gabe Amo ’09, who now is a staff assistant in the White House Office of Intergovernmental Affairs. “And then, as years went on, it was the commitment. He was the king of the follow-up.”

Reaching beyond the classroom

A key reason for Goodman’s success in the classroom is the fact that he’s remained an active practitioner of practical politics throughout his long career, just as his professors at Beloit were.

“What you learned wasn’t exclusively rooted in a textbook,” said Christopher Esposito ’94, a Democratic political operative. “He made it real-world. He helped you see and connect dots. Whenever I talked with him in or outside of class, I either learned something new or walked away with a different perspective on something.”

Goodman’s own political life has been centered around Rhode Island since he joined the Young Democrats at Brown in the early 1960s.

“Wisconsin Democratic politics were progressive politics about issues,” he said. “Rhode Island politics were about patronage and power.” He was Rhode Island chairman of Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1968 and attended that year’s infamous Democratic National Convention in Chicago, which he still recalls as “beyond insane.”

Goodman went on to serve as a senior advisor to leading Rhode Island political figures, including Governor Joseph Garrahy, Lieutenant Governor Richard Licht and Providence mayor Joe Paolino, who appointed him chairman of the Providence Civic Center Authority.

“I would call that very unusual,” said M. Charles Bakst P’94, who first met Goodman when they were at Brown together and later became a longtime political columnist at the Providence Journal. “There are doctors who teach and whatever, but in terms of political science professors, I would find it very unusual.”

“He’s the best of both worlds,” said Marsh. “There’s nobody more steeped in the academic rigors of political science, but he’s actually rolled up his sleeves and worked in the hard trenches that are political campaigns.”

Amo, a Rhode Island native, said he’s always impressed when he watches Goodman work the room at receptions with top elected officials in the state. “All of these politicians might as well be his students, because he’s telling them what needs to be done,” Amo said.

At home at Wheaton

Goodman flirted with leaving Wheaton at least twice in the 1970s. On one occasion, he was simply considering whether to move to a bigger school. The other time was when he was on the staff of Edmund Muskie’s 1972 presidential run and had dreams of working in the West Wing before the campaign collapsed. (Muskie instead offered Goodman a job on his U.S. Senate staff; when Goodman declined, the job went to future Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.)

He remains enthusiastic about teaching in his 50th academic year, and was busy collecting new survey data over the summer to use in his 101 class during the fall. He’s concerned about the general disillusionment of the new Millennial generation, saying it “changes the classroom environment for political science.”

Goodman is now 74, and says he “obviously” will retire from teaching at some point. “Oh, yeah, that’ll happen. I just don’t know when,” he said. “I’m not good at forward thinking. That’s probably why I’m still here.”

Goodman said he loves the “personal education” students receive in the intimate environment at Wheaton, which still reminds him of Beloit. He remains a fixture on the alumnae/i circuit, giving up to 15 political lectures a year to former students and their families around the country and overseas. And he’s proud of Wheaton’s success in recent years helping students win prestigious awards such as Rhodes Scholarships, saying he has more potential candidates in the pipeline.

“It’s like sports. Talent wins,” he said. “It’s not about class, or pedigree, or money. These kids have the talent? They win. It’s great.”

As much as anything, Goodman’s legacy is the generations of Wheaton students who discovered—through his classes, office hours, dinner conversations and follow-ups—their own passions and abilities.

“So much of our life is spent in our work, and he helped me find my life’s work,” said Goldman. “I can’t tell you how grateful I am for that.”

“People say this all the time, but the fact is there’ll never be another Jay Goodman,” said Marsh. “To have somebody who is that smart, that talented, that much of a political junkie, who actually did campaigns and has a Ph.D., and then to teach for 50 years? It’s hard to imagine that’ll ever happen again.”

Then and now

1965 – 2014

President

Lyndon B. Johnson – Barack Obama

Music

The Beatles – Taylor Swift

Movies

The Sound of Music – Gone Girl

Doctor Zhivago – The Hunger Games

TELEVISION

“Lost in Space” – “Big Bang Theory”

“Green Acres” – “Game of Thrones”