Is there a doctor in the house? Yes, two.

Alumni sweethearts follow passions together in careers as physicians

Time is precious for physicians Chris Wilbur ’05 and Danielle Erkoboni-Wilbur ’05. The married doctors not only manage a home with two young daughters, but also demanding, fulfilling careers with busy schedules.

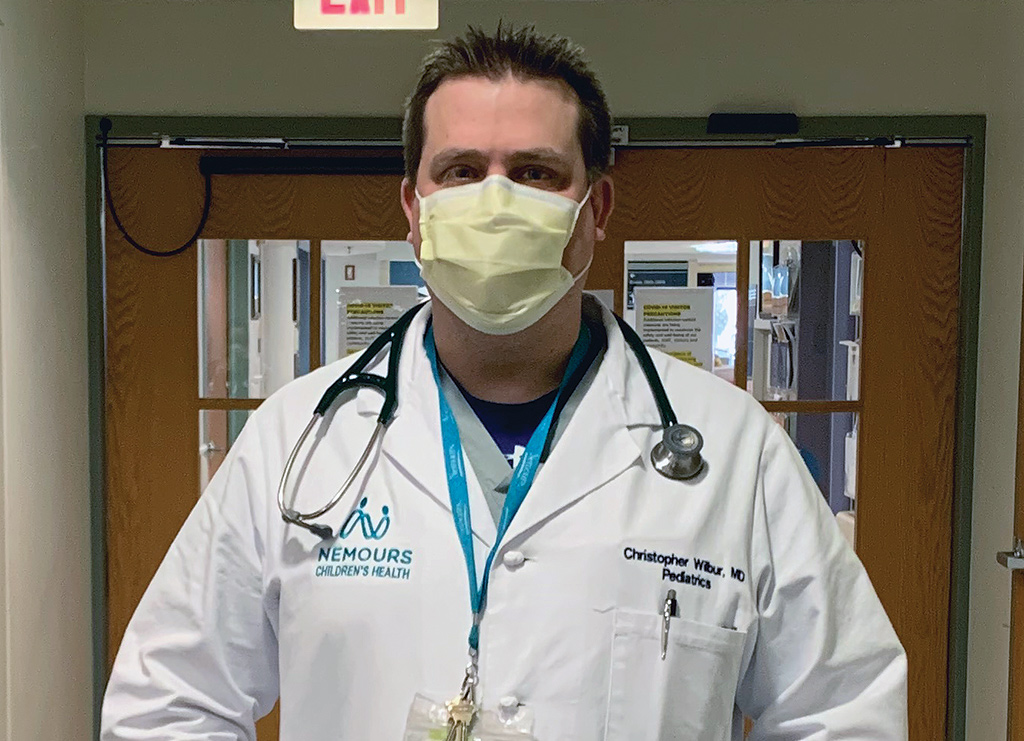

Chris, a pediatrician at both Jefferson Abington Hospital in Abington, Pa., and Nemours Children’s Health in Wilmington, Del., works eight 24-hour shifts per month while Danielle, a pediatrician and policy researcher at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, balances alternating clinical and research days.

Carving out 30 minutes in their complex day, the couple sat in the living room of their home in Blue Bell, Pa., and shared their remarkable personal and professional journey during a Zoom interview. Their mutual love for and support of one another enabled them to complete their science majors at Wheaton, medical school and residencies, and eventually thrive in their respective specialties.

They’ve come a long way since Wheaton, which helped them hone their scientific research and communications skills and, most importantly, provided the opportunity to meet during their first year at college and get engaged on the Dimple after graduating. Now, their days are filled with helping others have healthy lives that support dreams.

Chris and Danielle have a lot in common. Both felt a calling to become doctors at a young age.

“I had known very early on that I wanted to go into medicine and be a doctor. My mom used to read me a book when I was 6 years old called Simon Visits The Doctor, where the little boy went to the pediatrician. I would have her read it to me like three or four times each night,” recalled Chris.

For Danielle, her interest stemmed from positive experiences as a child in the doctor’s office. “I had a wonderful pediatrician who was very enigmatic; he was a pediatrician’s pediatrician with a red clown nose on and a toy box and funny little jokes and stories. I just loved that it was a comfortable space to be in.”

“I hope I do a fair job at emulating that relatable,jovial pediatrician today. I want to create a place that feels safe for kids and that’s something I work really hard on, even during the worst, toughest, busiest days in my practice,” she added.

Making a connection at Wheaton

The couple’s matching career aspirations meant that their paths inevitably crossed when they enrolled in similar courses at Wheaton. As first-year students, they found themselves in the same four science courses together. They both prized engagement on campus; Chris as the javelin thrower on the track and field team and Danielle as a member of the college’s coed a cappella group The Blend and as a Student Government Association senator. As alumni, Chris serves as the class secretary and Danielle is the class treasurer.

When asked which professor most shaped their Wheaton education, the couple looked at each other during the interview and Chris declared, “We both really have the same answer.”

That individual: former Professor of Chemistry and Chemistry Department Chair Elita Pastra-Landis, with whom they took the seminar course “The New Genetics.” Incidentally, it was in that course that they first met.

Pastra-Landis ran a welcoming and close-knit department where the Wilburs said they felt supported academically and personally. She also impacted their decisions about majors: Chris double majored in chemistry and biology and Danielle majored in chemistry with minors in biology and music performance.

“We tell her frequently that she shaped our lives and really helped to make Wheaton feel like a place that was really home,” Danielle said. “I recall when I wasn’t feeling so well one day and I came in and Elita said, ‘Come here’ and she felt my forehead and she was like, ‘No. You need to go home.’ And it was like having someone who just cared about you that extra way on campus. She is just phenomenal in that and taught us so much.”

Another lesson they learned from the professor: how to present complex scientific information.

“Chris and I talk about this all the time. There’s so much more outside of the hospital ward and the exam room and you are always talking with people and interacting with people and giving presentations, whether it’s to students or colleagues. So much of what we learned about being a professional really goes back to things we learned in that First-Year Seminar,” Danielle said.

Pastra-Landis fondly recalls her former students, whom she said were “top of the curve” in their classes. “They were students with imagination. In one lesson I asked them, ‘If you genetically engineer animals, what would you come up with?’ I just remember both of them went beyond applying what they were taught and came up with incredible answers.”

They also helped nurture the family-like environment of the Chemistry Department, Pastra-Landis said, by being hard workers and helping their classmates master the material.

“They were kind and helped others—a characteristic you’d hope for in any future physician,” she said. “Also, they urged each other on in the most positive way. They completed each other.”

The Wilburs, who began dating in March of their freshman year, echoed that they often spent time supporting each other academically. This habit followed them to medical school.

“We do very well as support partners in academics. There was no time when we were studying that it wasn’t together,” Danielle said. “I think we both survived and thrived because of that. … It continued through medical school, it continued through residency. In fact, it wasn’t really until our fellowship that we were ever at that point, probably after 15 years of being together academically, that we had a different job from each other,” she said.

Pursuing passions in pediatrics

After Wheaton, Chris and Danielle’s relationship continued to develop and grow—leading Chris to pop the question on the first anniversary of their graduation. And he knelt on one knee in the place where it all began: Wheaton, on the Dimple. Newly married, they were determined to stay together and not be long-distance during medical school. They applied to 41 schools as a couple and found that Chicago Medical School best suited both of their needs.

After completing the academic portion of their studies, they both pursued a yearlong internship followed by a three-year residency at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia. It wasn’t until after these residencies that their paths finally split: Danielle pursued an academic pediatric fellowship in research and health policy and Chris participated in an infectious disease pediatric fellowship helping children with serious infections and those with immunocompromised conditions.

In hindsight, these diverging paths made sense, Danielle said.

“Despite our paths that have always brought us together in pediatrics, Chris has always had a mind that is much more analytical. I have always wanted to be a big picture thinker, and public health and policy has been a place where I have spent time and thought,” Danielle said.

In Danielle’s case, she was selected for the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Pennsylvania. The goal of the program is to cultivate health equity, eliminate health disparities, invent new models of care and achieve higher quality health care at lower cost by educating and empowering medical professionals on these issues.

“It was an incredibly competitive program. I was with a cohort of seven others, both nurses and doctors from pediatrics and internal medicine and all other representatives there working together to gain knowledge around public health and policy,” she said. The experience compelled Danielle to also earn a master’s degree in health policy from the University of Pennsylvania.

At that time, Chris completed a three-year fellowship at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, studying pediatric infectious disease.

“I had worked with immunology and research before, so I was interested in immunocompromised types of conditions. At the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, there were a lot of patients with leukemia and cancer, and other immunocompromised conditions, and I gained experience working with a team caring for those kids and treating complex infections,” he said.

Providing care from a parent’s perspective

The married couple, having worked themselves through medical school and years of fellowships and residencies, are now physicians and researchers making a mark in their respective fields.

Danielle is both a practicing pediatrician at the CHOP Karabots Primary Care Center, Norristown, and she is faculty within the PolicyLab at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She also serves as the associate medical director of Reach Out and Read Greater Philadelphia, a nonprofit that provides books and guidance on early literacy in pediatric primary care clinics.

As for Chris, he works as a pediatric hospitalist at Nemours Children’s Health for a program called Care For the Hospitalized Child that offers treatment for children with common conditions, including pneumonia, cellulitis and asthma.

“I see patients that come in fairly sick and need to stay overnight with our nurses and our resident team. It’s fulfilling as I get to see them get better and improve. Little kids are very resilient and they get better within 24 or 48 hours and are in a much different place. Also, I get to see the parents be relieved that they’re better and that they get better,” Chris said.

The Wilburs both say that being parents makes them better doctors. They can put themselves in the shoes of the parents with sick children, and do their best to create environments that are warm and welcoming to families.

“We both do our best to wear the hat of a doctor when we’re with patients—but also the hat as a parent of young kids. I think it comes back to the foundation that drove us together, many years ago, that we both find it really important to make that connection with families and say, ‘Look, we are here for you,’” Danielle said.

The couple also support each other, as they always have, as their greatest and most loyal resource.

“That has led us to the point where we are today where we clinically have careers that are very supportive. We call each other with reasonable frequency when we have clinical questions, much to the chagrin of whoever happens to be having a moment or sleeping or whatever,” Chris said. “It’s a person you know will always pick up the phone.”