Getting comfortable… with being uncomfortable

Michael Easter ’09 book lauds benefits of pushing one’s limits

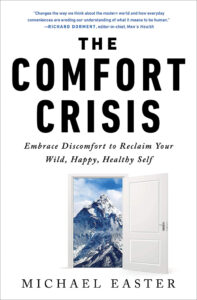

A journalist, writer and researcher, his book The Comfort Crisis (Penguin Random House, May 2021) asserts that too often we numb our lives. Modern conveniences like comfort food, smoking, alcohol, pills, smartphones and TV leave us feeling detached, depressed and removed from what makes us feel alive.

“A radical new body of evidence shows that people are at their best—physically stronger, mentally tougher and spiritually sounder—after experiencing the same discomforts our early ancestors were exposed to every day,” Easter wrote in his book. “Scientists are finding that certain discomforts protect us from physical and psychological problems like obesity, heart disease, cancer, diabetes, depression and anxiety, and even more fundamental issues like feeling a lack of meaning and purpose.”

Easter does not want to return to times when finding food was a life-and-death proposition or a harrowing struggle for survival. But he believes that individuals can find meaning, connection and an understanding of their own strengths through physically and mentally

demanding adventures in nature that he calls “misogis.”

Misogi is a Japanese word that refers to an act of ritual purification.

“More recently, the idea of misogi has been applied to … epic challenges in nature to cleanse the elements of the modern world. … They help their practitioners smash previous limits and deliver mindful, centering confidence and competence,” explained Easter in his book.

To illustrate the point, he chronicles his own misogi: a 33-day epic journey through the remote Alaskan Arctic backcountry to hunt caribou. Woven through his narrative is extensive research on evolutionary biology, natural and social sciences, and interviews with academics and spiritual leaders.

The Comfort Crisis already is receiving attention and accolades. Washington Post reviewer Tamar Haspel wrote that “Reading [the book] made me want to be better, and a book simply can’t deliver more than that.” Comedian Joe Rogan featured Easter in a nearly three-hour interview on his popular podcast “The Joe Rogan Experience” shortly after the book came out.

Easter’s ability to distill science for the layperson and connect and derive meaning and great knowledge from complex, interrelated ideas is fueling the success. And he credits his alma mater for harnessing this skill.

“My experiences at Wheaton greatly influenced how this book came together. Specifically, the ability to ‘think big’ and also find the common thread between seemingly disparate sources of information,” Easter said.

A turning point at Wheaton

Easter’s natural inclination to step outside of his comfort zone can be traced to his days leading up to Wheaton.

An outdoorsy youth who loved to rock climb, Easter chose Wheaton the old-fashioned way: through a conversation with the guidance counselor at his Utah high school. Together, they researched schools that offered small class sizes, a quintessential New England campus and a curriculum with a rich breadth of liberal arts courses. Wheaton provided the perfect fit.

The college’s curriculum that emphasized linking and making connections between disciplines made an impact on Easter.

He admits at first that he “didn’t want to have anything to do with science,” but a geology course that allowed him to study the field through multiple lenses ignited a lifetime interest.

A turning point occurred when he participated in a simulation in a course taught by Geoffrey Collins, professor of geology. For that project, the class partnered with students taking an international relations course taught by Professor of Political Science Darlene Boroviak. They took on the roles of both scientists and policymakers to examine factors impacting global natural resource management, including international treaties and climate change.

“I remember thinking ‘that was super fun.’ We were forced to think about this idea that is important and impactful, that really affects people’s daily lives, from different disciplines,” Easter said.

Collins, who served as Easter’s advisor, recalled Easter’s enthusiasm. Shortly after the simulation, he helped Easter design an independent major that honored his interest in the connection between the social sciences and natural sciences. He graduated in 2009 with a degree in politics, economics and the science of natural resources.

“He thrived on thinking how everything fits together and had a natural ability with science. He also served as my teaching assistant in geology and had a natural ability to help students out in the field,” Collins said.

A course in environmental writing cultivated Easter’s interest in writing—and eventually compelled him to enroll in a master’s degree program in journalism at New York University.

“I grew up being a total magazine and book junkie—reading Outside and Esquire magazines and both nonfiction and fiction. But I didn’t do much writing. I took that class and discovered that I really like to write,” he said.

The path to Comfort Crisis

Easter found quick success following graduate school. He landed a job as fitness editor at Men’s Health magazine, where he developed, reported, wrote and edited stories for the magazine’s print edition and website.

“This entailed piecing together often-disparate information gained through human, scientific and other primary and secondary sources to construct compelling, accurate and cohesive written narratives,” he said.

His writing has appeared in Scientific American, New York, Women’s Health, AARP, Outside, Details, Men’s Journal, Cosmopolitan and FiveThirtyEight.com.

In 2017, he joined the University of Nevada-Las Vegas as a full-time visiting lecturer at the school’s Hank Greenspun School of Journalism and Media Studies. In 2019, he co-founded the school’s Public Communication Initiative, a think tank that helps academics, business and governmental organizations improve their communication with the public.

But, as he describes in The Comfort Crisis, his early professional success masked struggles with addiction.

“I had an enviable career at a glossy magazine as a health journalist dispensing advice on how to live a better life. I was good at the job. But I wasn’t exactly living the wisdom I wrote. Most of my mental energy was spent toggling back and forth between being drunk and obsessing over the next drink,” he wrote.

After hitting a low point, he managed to quit cold turkey, and begin rebuilding his life. Part of that journey was his revelation that he was “marinating” in comfort; from his temperature-controlled house to his ability to quell boredom with a smartphone to his access to no-effort highly caloric foods.

With inspiration from Donnie Vincent, a biologist and documentary filmmaker, he decided to go on a five-week hunting trip to the Alaskan Arctic tundra in search of caribou—and write a book about it. He faced freezing temperatures, the threat of grizzly bears, cliffs and long hours without modern distractions—and came away with a new outlook on life.

A journey to self

As Easter narrates his Alaskan adventure, he shares insights from data studies and interviews on how we’ve evolved and adapted to our lives of comfort. He also offers science-based recommendations to improve our health—such as taking long, weighted walks (called rucking) to build endurance and strength.

His book describes topics as diverse as why acknowledging impermanence in Bhutan makes the Bhutanese among the happiest people and the link between Icelanders’ long life spans and their long history of discomfort. His research touches on the “loneliness epidemic” in the U.S.; the importance of building “the capacity to be alone;” and how time in nature leads to documented improvements in our

immune systems, as well as productivity and creativity.

Easter also uncovers research on the creative and mental benefits of boredom, which came into full focus during long days in the Arctic.

“The key to improving productivity and performance might be to occasionally do nothing at all,” he writes.

Easter, who spent years weaving his research into a book, hopes it encourages people to undertake their own misogi. He said these challenges are for anyone, at any level.

“You have to start where you are. There are many ways to slowly leave your comfort zone,” he said.

Easter remains faithful to his own yearly misogi. This year, he pushed himself to run three times the distance of his longest run of 16 miles.

“I went out and tried to run four laps around Red Rock Canyon [located in Nevada], a 12-mile loop. On the third lap, I thought ‘no way, this is the last one. It was a good idea, fun while it lasted.’ But when I finished that lap, for whatever reason, I kept going. Something was going on that pushed me to go that extra lap. It makes me think to myself, ‘What else am I selling myself short on? Do I have these certain limits that I’m not correct on?’”

<>A different view

The Comfort Crisis dedicates a chapter to “problem creep”—the propensity for humans to always look for problems, even in the absence of them.

Realizing this tendency has been the biggest takeaway for him, Easter said.

“By looking for problems, you lose perspective and you lose gratitude and that colors the rest of your day,” he said.

Easter said he experienced “a complete perspective shift” upon returning from Alaska. Now, even something as regular as going to a dinner with his wife feels different.

“We go to this restaurant where the food is amazing, but service is the worst. Instead of focusing on why they are taking so long—this inefficiency, that inefficiency—I can now sit in that restaurant with crappy service and think, ‘I’m warm right now. I’m about to eat an ungodly amount of calories. They will bring water eventually, and I don’t have to hike down to a spring surrounded by grizzly bears.’ That makes me a better person,” he said.