Collaborating, contributing to COVID-19 insight

Literature review project offers authentic research experience during pandemic

In late spring 2020, with the rise of the coronavirus and widespread lockdowns in place, Wheaton College students grappled with how to spend their summer.

“As a rising senior biology major, I was looking for some additional research experience to prepare for graduate school. My options were getting more and more limited as companies and schools shifted to remote work,” Benjamin Hanna ’21 recalled.

Anna Lally ’21, a neuroscience major, meanwhile, was eager to spend time in the lab.

“Third- and fourth-year STEM students tend to look for outside, hands-on experience during the summer. Because of the pandemic, so much of our ability to work in institutions was eliminated,” she said.

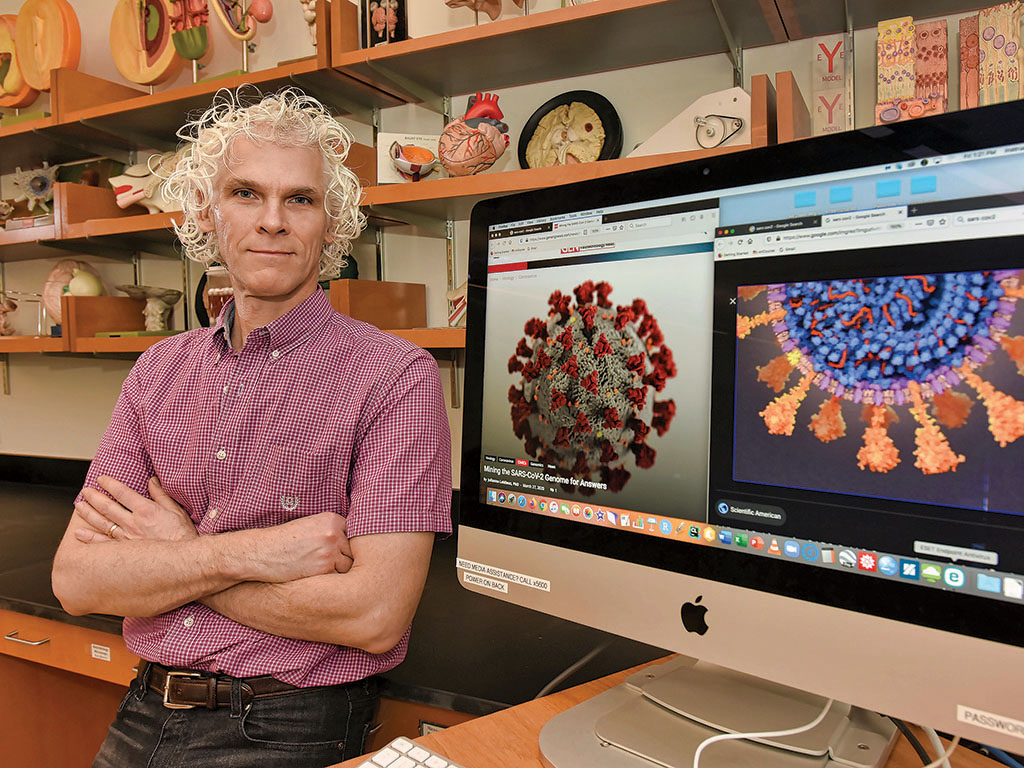

Fortunately, Professor of Biology Robert Morris reached out to Hanna and Lally with a potential summer research project that not only would give them the real-world research experience they craved, but a chance to study the most critically important topic of the day: COVID-19.

Hanna and Lally were not alone; they were among dozens of students, including graduating seniors, who took up Professor Morris’s offer to join a project that would contribute to answering questions that science and medicine had about the novel virus.

In its totality, the AI-assisted COVID-19 Literature Review Research Project was wide-reaching in scope. It involved the virtual collaboration of more than 50 students and recent alumni, four faculty members and staff from the Wallace library.

“The project gave students who thought they would have nothing to show for this lost summer an authentic, mentored research experience that they can put on their CVs,” Morris said.

Solving a problem while engaging an opportunity

In spring 2020, Tayab Waseem—a software engineer and medical student—reached out on the COVID-19 National Scientist Volunteer Database for assistance on a project to test the effectiveness of a program he developed that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to conduct literature reviews.

Professor Morris immediately recognized the opportunity this would present for students unable to secure internships or other research positions due to the pandemic.

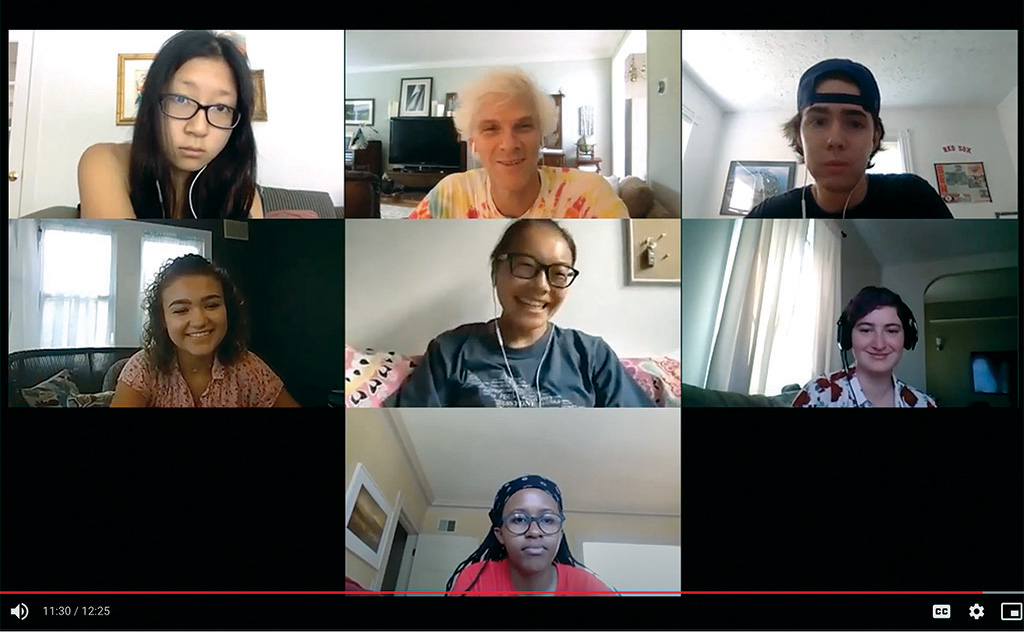

To assist Waseem, Morris recruited students to the project. The group was organized into teams, each led by one of four participating faculty members: Morris, Associate Professor of Psychology Kathleen Morgan, Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Hilary Gaudet and Faculty Associate in Biology Shari Ackerman-Morris. In Zoom meetings, Wheaton Sciences Liaison and Technologist Jillian Amaral provided training on proper techniques for conducting literature reviews, while Waseem taught the students how to use his AI software.

“There was warm reception and enthusiasm from students. We didn’t know what was going to happen, and it was exciting that way,” Professor Morris said.

From May to June, students identified questions they found interesting regarding COVID-19. They then mined databases for scholarship articles related to these questions using Waseem’s AI software and standard research methods, and subsequently wrote mini-reviews summarizing the research.

In late summer and fall, a subgroup of students stayed on to synthesize their findings into review papers, which they submitted to scientific journals and open source sites like medRxiv during the fall and winter.

Hanna said he enjoyed being a part of the project, as he learned new research approaches, team skills and was able to have a productive summer.

“I greatly improved my reading and writing, my ability to analyze papers quickly, and data collection and processing. I also developed important teamwork skills that I will carry with me to any lab in the future,” he said.

The experience showed Lally that in-person collaboration is not the only way to conduct successful research.

“This project was a unique learning experience that taught me that virtual collaboration, while occasionally difficult and frustrating—because who doesn’t want to just be talking with their peers in Emerson—is very possible and can lead to great work,” Lally said.

“It speaks to the Wheaton science community as a whole and the mentorship of many professors to give such a group of students not only the opportunity to work on a project such as this, but the confidence to do it as well,” she added.

Question: What is the incubation time of COVID-19?

Principal investigator: Shari Ackerman-Morris

For Megan Fydenkevez ’22 and Caitlin Daley ’20, the chance to research COVID-19 was one they could not pass up.

Fydenkevez, a neuroscience major on a pre-med track, already was learning about COVID-19 as part of her summer Wheaton course, “Virology,” taught by Amy Beumer, visiting assistant professor of biology.

“I had been perusing online journals and following the latest information about SARS-CoV-2 prior to and during this class. I immediately knew that I had to be a part of this project,” she said.

Daley, a biology major, was excited about the prospect of contributing to a quickly growing research base about COVID-19. “I hoped that our research would have a small impact on the global efforts to understand and overcome the virus.”

Fydenkevez and Daley served as leaders of Faculty Associate Shari Ackerman-Morris’s team of 13 students. They focused on determining the average incubation time of COVID-19 while taking into consideration a number of factors, including age, sex and location of those who contract the virus.

Once the summer phase was over, the team leaders delegated research assignments among the remaining students to search for additional papers on that topic, extract more data, and then synthesize the research and write specific areas of their review paper.

Their group’s paper, “A Systematic Review of the Incubation Period of SARS-CoV-2: The Effects of Age, Biological Sex, and Location on Incubation,” was compiled and analyzed using 21 quantitative studies. The paper was posted on medRxiv, an internet site that distributes unpublished online articles about health sciences, on Dec. 24, 2020.

Based on the data extracted, the team found an overall mean and median incubation period for SARS-CoV-2 of 5.894 days and 5.598 days, respectively. They also concluded that the incubation period did not statistically vary for biological sex or age, but some studies suggest a longer incubation period in the young and elderly.

The team also reported that researchers have discovered an inverse relationship between incubation period length and virus severity.

“We suggest that people who experience more severe disease due to SARS-CoV-2 may have a shorter incubation period,” according to the paper.

Faculty Associate Ackerman-Morris lauded the students, who developed skills in paper writing, statistical analyses and generating tables and figures—all while working as part of a team.

“It was an interesting collaboration, from my part, because I wasn’t in the trenches. I took a step back and let the students lead. I got to play a mentor,” Ackerman-Morris said. “They really did fabulous research, which showed when they finally condensed and wrote the paper.”

Through the research project, Fydenkevez said she vastly increased her understanding of the research process and COVID-19.

“I cultivated research and leadership skills while working toward a published review paper. I was very pleased with the experience of working with our team,” she said.

Question: What is the risk posed by common domestic animals to humans, regarding transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus?

Principal investigator: Kathleen Morgan

For Anna Lally ’21, a neuroscience major, the COVID-19 project helped restore her mental health at a time when so much in the world was on hold.

“I was living at home, with no physical contact with friends I’d made in college thus far. That lack of agency and interaction seemed to have a great impact on myself and many of my peers,” Lally said. “Participating in this project helped me feel that I got a bit of that agency back, simply by learning and educating myself, working with peers, and knowing that the work we were doing had the capacity to be meaningful for not only us, but our family and friends, and potentially the scientific community.”

Lally, Amanda Flanagan ’20 and llyan Lin ’23 led a team of 11 students who data-mined a total of 127 manuscripts published between November 2019 and August 2020 for relevant information regarding transfer of the SARS-CoV-2 virus from animals to humans.

Based on their findings, ferrets, cats, minks and golden Syrian hamsters seem like the best candidates for future research since they are highly susceptible to COVID-19. They also found it unlikely that domestic pets, such as dogs and cats, will transmit the virus to humans, but infected owners have a chance of infecting their pets.

According to their research, they identified multiple factors that seem to matter regarding animals and possible COVID-19 transmission. Animals in whom the structure and expression of ACE2 receptors (a type of protein on the surface of cells) were most similar to those same things in humans tended to be most susceptible to the virus. The density of an enzyme called TMPRSS2 protease in different parts of the animal’s body, which can alter ACE2 receptors to permit entry by the virus, also increased the probability of transmission.

The group submitted their paper to Animals, which is publishing a special issue on the impact of COVID-19 on animal management and welfare.

The three students who led the process of synthesizing the studies into one complete paper said the project taught them how to collaborate in a virtual environment.

For example, Lin explained that the group wrote the paper as a team.

“We would volunteer to do different sections of the paper, but it wasn’t one person editing or one person working on the introduction. Personally, I’d skip around from editing what we have, writing and doing research as new information came up,” Lin explained.

Lally said collaborating virtually proved to be challenging, as she wasn’t able to rely on body language and other cues when communicating with her peers.

“When all of that disappears, you’re left trying to navigate the new Zoom workspace, and it is difficult to be as efficient and effective when working as a team,” she said. “I learned willingness to hear constructive criticism, even when you’ve been on Zoom for an hour and it becomes hard to believe there’s another tired, hardworking student behind the little image at the top of your screen.”

Flanagan said she gained insight into the publication process for scientific papers.

“It was great to work with people from different biological science backgrounds and interests,” she said.

Associate Professor of Psychology Kathleen Morgan said this type of virtual project was unprecedented for Wheaton, but ultimately a success.

“I think it was an incredible model for how to do this kind of collaborative work. Students were incredibly responsive to each other and great collaborators, learning to criticize each other’s work in a good way,” she said.

Question: What is the COVID-19 nasopharynx viral shedding time period and what are the implications on testing effectiveness?

Principal investigator: Hilary Gaudet

Nick Kelly ’21, a biochemistry major on a pre-med track, received the email about helping out with this project right when he started an internship at the Fertility Center at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, where he worked on a different AI-based study.

“The fact that AI was such an ongoing theme in both research studies helped prove to me that this sort of software will help change how both research and medicine are practiced. If AI is making such a big difference, then an opportunity to study COVID-19 using AI was too hard to pass up,” he said.

Sydney Murphy ’21 said she loved the idea of testing AI software.

“My motivation was not only because it was a timely topic, but it was also to have the opportunity to create an aid for other researchers. This includes students similar to myself who were in need of a cohesive summary of the current research on the virus to launch new research projects leading to a vaccine,” said Murphy, who is majoring in neuroscience and German.

Kelly and Murphy joined the 13-student team of Hilary Gaudet, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry, that examined different methods of performing COVID-19 tests. Their work culminated in the paper “Testing and viral shedding detection of SARS-CoV-2 via nasopharyngeal swabs and other methods,” which the team submitted to Advances in Virology in September 2020.

Gaudet’s team researched how effective the nasal swab is at picking up the virus at different time points during an infection. They looked at other forms of testing, including upper respiratory tract sputum sampling, saliva and oropharyngeal sampling, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid testing, blood sampling and fecal sampling.

Five students stayed on in the fall to draft the paper, which they divided into designated sections for each student.

“We all participated in proofreading and worked together to improve the paper as it was going through the peer editing process,” Kelly said. “Collaboration with our professor, Hilary Gaudet, was most helpful in guiding us through the editing process. By the final submission of the paper, I felt that I had developed a more in-depth understanding of the research and publication process and felt more confident in my research and writing skills, which I anticipate will aid in the success of my future career.”

Their results confirmed the accuracy of nasal swab testing. They found that fecal sampling has shown that shedding of the virus in the digestive tract can extend far longer than through nasal tests. Oral samples have proven to be a second specific testing method that is much less invasive than nasopharyngeal testing, making it an ideal new candidate for wide-scale testing, according to their research.

Murphy said she enjoyed learning a lot about SARS-CoV-2 infections—enough to be able to educate others about the dangerous effects and best prevention methods against infection.

“I feel more informed of the current situation than if I had not taken this research opportunity and am thankful to have had the privilege of doing so,” she said.

For Kelly, his research during this project steered him to the subject of his honors thesis.

“Now, I am using a meta-analysis to see if there are any significant differences between blood types and COVID-19 severity and infection rates. In my current honors thesis study, I am seeing a very significant correlation with O type blood and a lessening in the COVID-19 positivity rate,” he said.

Question: What is the correlation between humidity and temperature and the number of COVID-19 cases?

Principal investigator: Robert Morris

In spring 2020, the topic of climate impacts on COVID-19 transmission was both timely and significant, especially as U.S. researchers speculated that COVID-19 might die out in the summer, as many viruses do. At that time, scientists were concerned about increased transmission in the following colder months.

The question Professor of Biology Robert Morris and his team of 13 students posed was whether there is a correlation between humidity and temperature and the number of COVID-19 cases. The team analyzed and extracted data from 125 relevant articles and compiled the information into one comprehensive spreadsheet.

Benjamin Hanna ’21 served as one of the lead writers. He organized frequent Zoom meetings during which everyone shared their progress and findings and discussed formatting spreadsheets and data, and various ideas for constructing the final paper.

Their work resulted in a paper, “Correlation of humidity and temperature with COVID-19 transmission: a systematic review of published literature,” which they will be submitting to medRxiv and a peer-reviewed journal that co-author Tayab Waseem is identifying.

The results of a meta-analysis of correlational data indicate that temperature and humidity are both positively and negatively correlated with COVID-19 cases, with no obvious patterns emerging.

Their results indicated that temperature and humidity are both poor predictors for COVID-19 transmission when taking multi-country and single-country studies into account since, when looked at systemically, published correlations contradicted each other.

“The unexpectedly wide range in the published data suggest that the seasonal factors of temperature and humidity alone will not be sufficient for predicting trends in SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility,” according to the team’s abstract.

Hanna said he was definitely surprised by the findings of the research.

“I expected there to be clearer data that indicated COVID-19 transmission would be worse at high temperatures or low temperatures,” Hanna said.

Biochemistry major Helene Mantineo ’21, who led the team in compiling the research, said she enjoyed learning more about COVID-19 and growing as a scientist. She developed leadership skills managing a group of students with different levels of experience—from first-year students to graduating seniors.

“I had never led a whole team before, so it was a big growing experience. It can be hard to balance what you know and what other people know on the team. I had to let go of controlling the process and gain trust with everyone,” she said.

Hanna said his biggest insight from this project is seeing how research is not just done in a lab with samples, solutions, pipettes—but that you can also make discoveries through reviewing literature.

“Data analysis is a critical component of science and it is important to look through published articles for similarities and differences in data so that there can be a better overall understanding of a specific topic,” he said.

Morris said his team truly enjoyed the ability to help the scientific and medical community by creating a resource that didn’t exist without their research.