Translating Tibetan Buddhism for today

Michael Sheehy ’98 is a leading scholar of contemplative practices

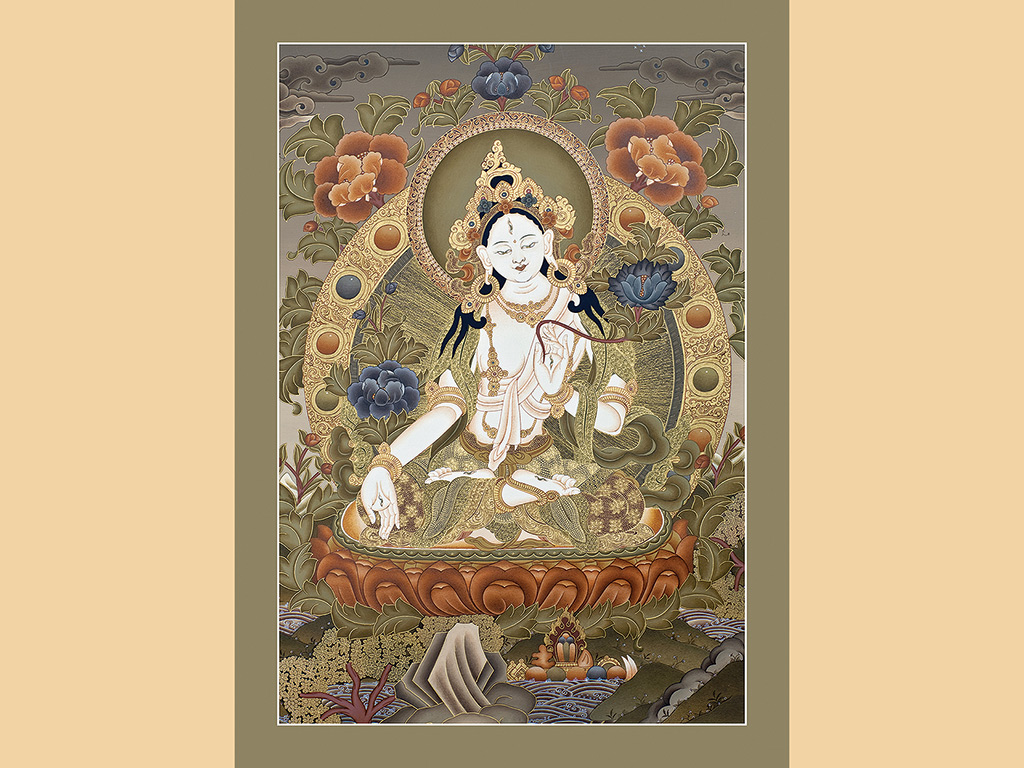

A single moment can crystallize one’s purpose. For Michael Sheehy ’98, that flash of insight occurred 25 years ago as a Wheaton student, when he encountered an image that had a life-changing impact on him.

“I was on the second floor of the Wallace library, where there is a sitting room with art books. I came across a book on Himalayan art. For some reason, I was so captivated by this painting of a female Tibetan deity. It was a close-up of her face on a fresco of this deity named White Tara, this goddess,” Sheehy recalled. “I remember feeling mesmerized. The world had stopped. I was enchanted by this deity and that was it. From then on, I asked myself, ‘Who is she? What is this?’ I had to know.”

For Sheehy, that discovery solidified his desire to explore Buddhism—particularly Tibetan Buddhism. He enrolled in as many courses as possible at Wheaton on Asian art, culture, religion, history and politics, and studied abroad in Japan, Nepal and India, where he could see firsthand Buddhism in practice.

Twenty-four years after graduating, Sheehy is tirelessly working to preserve knowledge of Tibetan literature and contemplative practices. Over the years, his journey has entailed years of field research and contemplative practice, including at a monastery in remote Tibet, and efforts to better understand the intersection of science and Buddhism.

He currently serves as the director of scholarship at the Contemplative Sciences Center at the University of Virginia.

Pursuing meaningful experiences—the most natural of human impulses—is at the heart of contemplative life, said Sheehy.

“Among our records of the earliest humans from painted caves—such as Lascaux in southern France—we have evidence that humans were seeking to give meaning to their world. Practices of contemplation are designed to elicit meaningful experiences and imbue life with meaning,” he said.

Sheehy believes a better understanding of contemplative practices holds the key to confronting global challenges.

“We are living during a global epoch of heightened distraction and rapid change. This moment requires new ways of thinking and responding, new ways of being in the world. Because of the challenges that we face globally, humanity is hinged on how we shed maladaptive systems and retool ourselves with new systems of technology.

“This has historically been the case for humans and other species. Contemplative practices are a human technology that we can use to retool ourselves with greater attentional, emotional and embodied skills,” he said.

Probing into the nature of consciousness

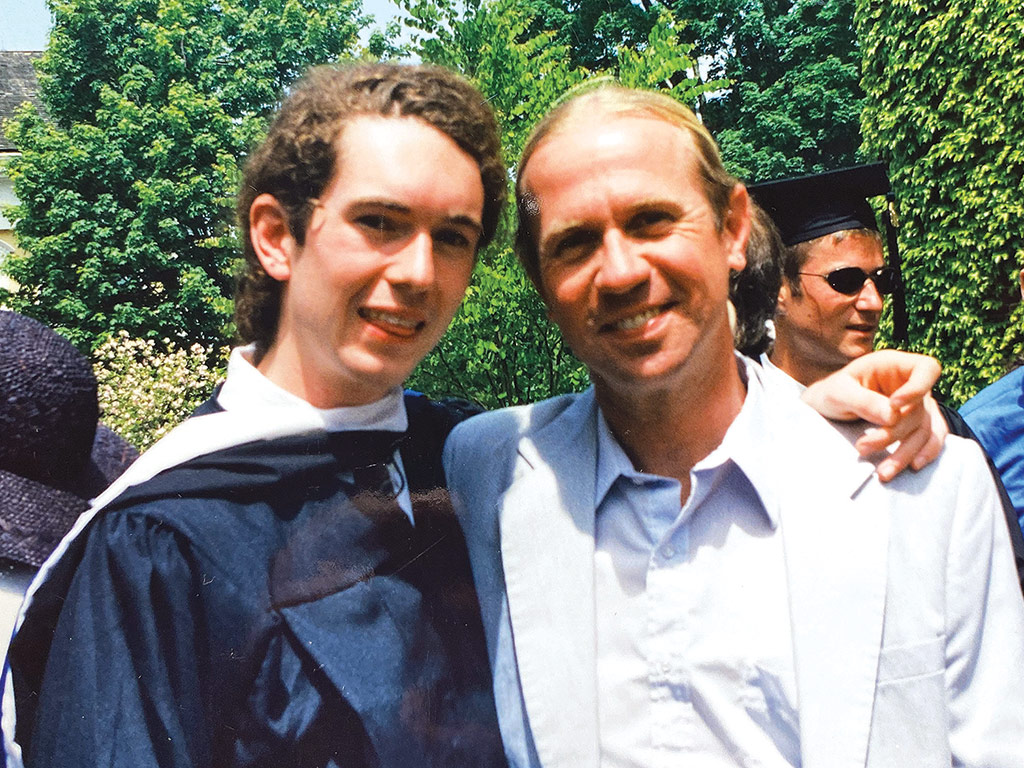

In March 2022, Sheehy’s journey brought him back to Wheaton to present the 32nd Annual Martin Lecture in Religion. It was the first time in the lecture’s history that an alum was chosen and invited to present their scholarship, according to Professor of Religion Jeffrey Timm.

In his talk, Sheehy discussed various Vajrayana Buddhist practices from the Tibetan and broader Himalayan regions. These practices, which require a practitioner’s undivided attention, are aesthetically oriented, formal and include meditation, yoga and other techniques that involve control of bodily postures, voice and mind, he said.

“There’s an astonishing variety of these practices. It’s important to think about them as a kind of species of knowledge that’s endangered because of social, cultural and historical forces,” he said.

Among the many practices that he described included “dream yoga,” which entails recognizing a dream as unreal and engaging in lucid dreaming, and “tummo,” a yogic practice to induce ecstasy by regulating body heat. For the latter, he said the ability to generate body heat through a sequence of breath retention and forceful breathing, physical exercise and visualization has been studied and confirmed by scientists.

For Sheehy, meditation and other contemplative practices are integral to being human.

“The nature of consciousness is one of the great riddles of our time. These contemplative practices provide methods to experimentally probe our subjectivity and provide a methodology to look into our minds and inner world,” he said.

Shuchang Gu ’23 said Sheehy’s lecture opened her mind to what human beings can achieve with their bodies. She added that people often forget the original context of contemplative practices.

“Contemplative practice is more than a way to relax. It is a route to explore ourselves not through tools or instruments, but directly experiencing it; it is a pursuit to discover something from the inside instead of from the outside world; it is a method to refresh our expectation of possibility,” Gu said. “Depriving it of its original context not only affects our practice of it but also limits us in appreciating its value and makes us ignore what it can contribute to the future.”

Professor Timm said he hopes all students benefited from the lecture.

“My goal was to try and get the word out, to any student interested, that you are not the sum of your desires, thoughts and feelings. Alternating between hope and fear is not the only way to live your life. There is a bigger story beyond being an ego in the persona field. And, when you are ready to find out for yourself, here are some views, tools, techniques and practices that have helped some people wake up to reality, beyond cultural constructivism and identity politics, to the way it really is,” Timm said.

A path to a calling

A career as a leading scholar in Tibetan Buddhism may seem unlikely for Sheehy, who was raised in a small town in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

His grandmother planted the seed that cultivated his interest in contemplative practices. She had a room in her home, which she painted blue, where after school she would encourage a young Sheehy to relax, calm the body and mind, and exercise his imagination.

“My grandmother, in her own gentle way, started to introduce me to meditation, without calling it meditation, as well as relaxation and visualization techniques,” Sheehy recalled.

Eventually, as a teenager, he stumbled upon the word “meditation,” which he connected to his experiences at his grandmother’s house, and which led to his discovery of Asian philosophy and Buddhism.

At Wheaton—notably after the life-clarifying moment in Wallace library—he doggedly pursued coursework in Buddhism and chose to major in Asian studies. Professor Timm, from whom he took the course “Buddhism Thought and Action,” eventually—in part due to Sheehy’s encouragement—began offering a series of Buddhism courses.

Sheehy’s passion for contemplative practices was ever-present as a Wheaton student. With two like-minded friends, he organized meditation and yoga groups.

“We created this kind of environment where we had identified the faculty members at Wheaton who were teaching Buddhism, and what we could learn from them, and we created spaces where we could practice. So, we had this academic intellectual side and we also had this contemplative extracurricular side,” he said.

There also were clear signs of Sheehy’s gift for research. Timm fondly recalled the alum’s honors thesis, a tour de force account on human rights in Tibet and the Buddhist path of healing social conflict. At over 184 pages, it’s the longest honors thesis in Timm’s memory.

“What’s super amazing and remarkable to me is that now, 24 years later, Michael is tilling the same fields with an ever-deepening skillfulness, wisdom and compassion,” Timm said.

Himalayan journeys

Throughout his career and life, Sheehy has carefully balanced his love of research and his passion for contemplative practices.

On the academic side, he dedicated himself to learning the Tibetan language. During his junior year at Wheaton, he spent a semester studying at Naropa University first in Kathmandu, Nepal, and then in Boulder, Colo., where he secured private lessons in the Tibetan language.

After graduation, he spent 18 months in India following the historical pilgrimage route that traced the life of the Buddha. He then lived in Bangkok, Thailand, where he worked as a writer and editor for a small nonprofit focused on socially engaged Buddhism.

At that point, low on money and trying to sort out his future, he was at a crossroads.

“I knew, at the time, because of my experience in Asia, because of my experience at Wheaton, and back to my experience with my grandma, I not only wanted to study Buddhism academically and get my Ph.D., I also wanted to make sure it was complemented by an experiential education,” he said.

Sheehy moved to New York City, worked temp jobs, and enrolled in Tibetan language courses at Columbia University. After one year, he moved to California to study Buddhism. He pursued his Ph.D. in Buddhist studies at the California Institute of Integral Studies, and concurrently at the University of California, Berkeley.

“My doctoral work was on a very small, really unknown tradition of Tibetan Buddhism called the Jonang. It was not known outside of Tibet and was thought to be extinct. My dissertation showed that the tradition is still alive and described its history, thought and philosophy,” he said.

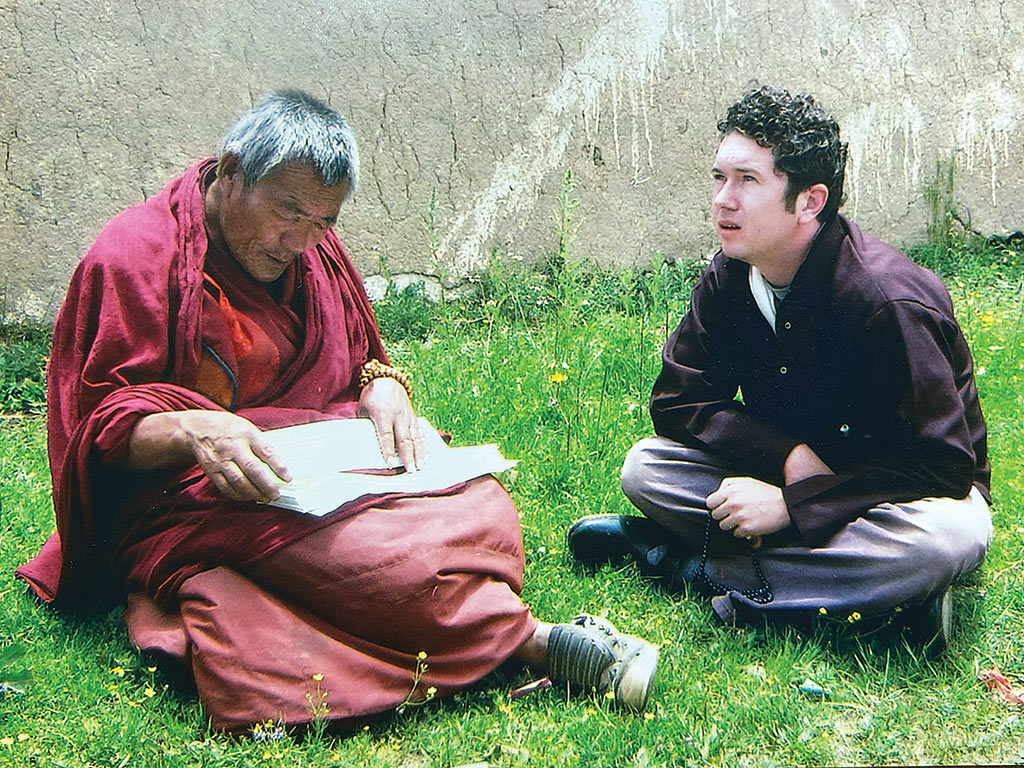

For his research, Sheehy ventured to remote places to seek out rare manuscripts. He lived in a monastery in northeastern Tibet for three years where no one spoke English and there were no other foreigners.

The experience exposed him to Tibet’s rich literary tradition.

“Tibetan culture has one of the greatest literary cultures and one of the great literary archives that humanity has produced. There’s extraordinary Buddhist contemplative literature written in the language,” he said.

While in Tibet, he met and fell in love with his wife, Yeshe Tsho, from Ngawa. (Today, they share two daughters, ages 13 and 10.)

He also began corresponding with the late E. Gene Smith, a scholar of Tibetan literature and history who founded the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center (now called the Buddhist Digital Resource Center). Smith invited Sheehy to work with him at the center as a postdoctoral researcher in 2008, where he was building a digital library of Tibetan literature. Sheehy became the editor and then eventually the director of research at this organization, where he stayed for eight years.

“I ran projects all over Tibet—field research projects to preserve rare, endangered literature, to digitize and catalog it. And then, in 2016, I moved to Cambridge, Mass., and this work became part of the Harvard Library,” he said.

After many years of fieldwork, including his time in the monastery and running digital manuscript projects, he circled back to his other passion: contemplative practices.

“I had to return to my origins. I wanted to pivot and focus on contemplative practices, meditation and yoga,” he said.

Sheehy took a job in Charlottesville, Va., as the director of programs at the Mind & Life Institute, an organization founded by the Dalai Lama and a neuroscientist named Francisco Varela that explores the intersection of Buddhism and science.

“I worked very closely with the leading neuroscientists of meditation and organized interdisciplinary dialogues between Buddhist contemplatives, philosophers and scientists,” he said.

In 2018, Sheehy joined the Contemplative Sciences Center at the University of Virginia, where he researches meditation and yoga manuals, procedural instructions and histories of different contemplative practices. He also serves as a research assistant professor in Tibetan Buddhist studies in the Department of Religious Studies.

One of his major projects at the center is the Generative Contemplation Initiative.

“My main research project looks at the fundamental principles of contemplative practices, identifies them, and then tries to understand the building blocks of practice and the context in which practices were performed. We are thinking through how practices can be designed based on understanding these fundamentals, like learning a new language. We consider this building toward a ‘contemplative fluency,’” he said.

Sheehy’s oscillation between study and practice has enabled him to access Buddhist culture and traditions. Now his focus is on helping interpret Tibetan knowledge and practice for broader audiences, which he calls “cultural translation.”

“What I mean by a cultural translation of these practices is a way of communicating how we can draw from our immense heritage of human knowledge to innovate and adapt these practices for our current time and culture, whatever that may be. If we are to invest in technologies, which I believe we must, they should enhance the self, body and mind,” Sheehy said.