Nurturing potential, in cells and students

Professor and alum collaborate on cutting-edge science

Sitting around laboratory tables in Room 1145 of the Mars Center for Science and Technology, Philip “Phil” Manos ’08 and Professor of Biology Robert Morris bantered like old pals.

There was palpable excitement in the air, as they had just finished a collaboration that brought Manos—an accomplished stem cell researcher and entrepreneur—to Professor Morris’s course “Neurobiology,” which is the study of cells in the nervous system.

Stem cell research holds the promise of major medical breakthroughs; some researchers believe new stem cell technologies could lead to better therapeutics and potentially even cures to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

During Manos’s three visits to campus, students benefited from working directly with a pioneer in stem cell technology who once was in their shoes.

Manos brought with him a type of nerve cells (neurons) derived from human stem cells, giving students an opportunity to experiment and test their own theories in class.

He also shared with the students his personal journey, one that took him from working at major research facilities and publishing academic papers—all without a Ph.D.—to launching his own company. As president of EverCell Bio, he provides customizable stem cell research services to scientists actively seeking cures to major diseases for the next generation of personalized medicine.

That December afternoon in the science center, staff writer Laura Pedulli enjoyed a conversation with the alum and his former professor. Their enthusiasm for science flowing, Pedulli had to ask on several occasions to bring their cerebral conversations down to earth, as the duo reminisced about the past, celebrated their present collaboration and discussed what the experience meant to Wheaton students.

Laura: Phil, what excites you the most about stem cell research?

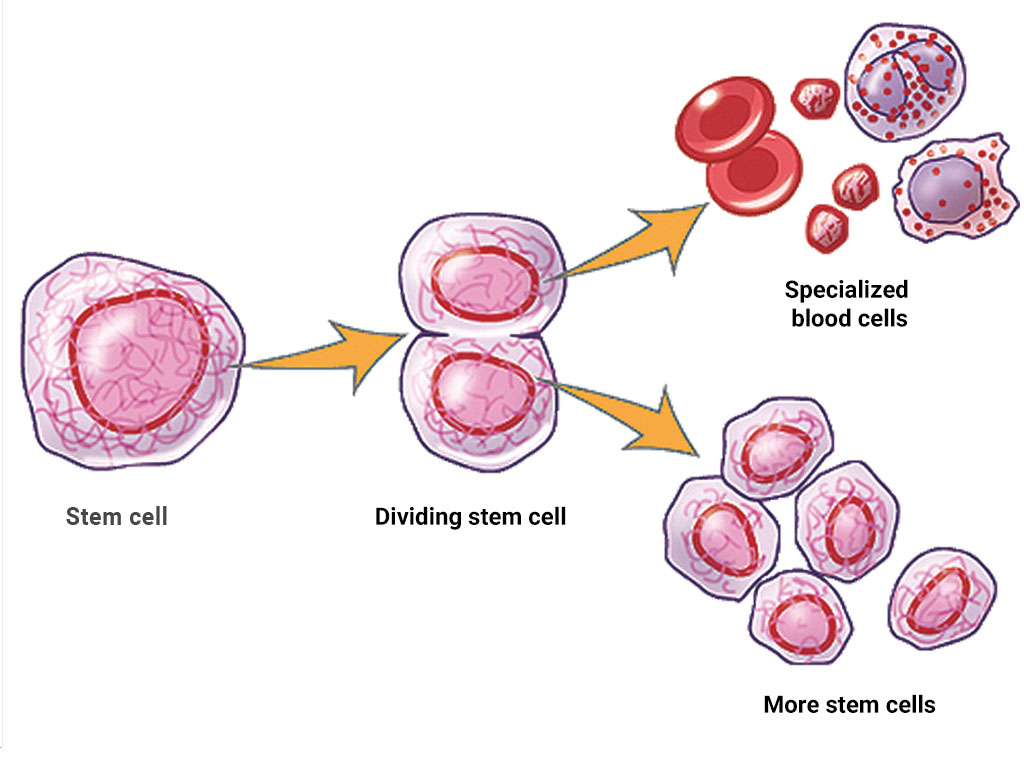

Phil: “It’s the sheer incredible power that this technology holds. When we say ‘stem cell technology,’ that really includes new ways to obtain stem cells. You can take blood or skin cells from an adult human and reprogram them into embryonic-like stem cells, called induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. From there, we can turn them into theoretically any cell in the body. This technology can not only potentially help replace cells that are lost in degenerative diseases, but it’s also actively supporting efforts to help make better drugs.”

Laura: What types of diseases will stem cell therapies be able to target?

Phil: “Certainly, I think of the neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, especially as the aging population gets larger.”

Robert: “I agree that neuro-degenerative diseases are one of the most important therapeutic avenues for humans to tackle right now. I tell students that they need to plan for 80-year careers and 120-year life spans, because by the time they’re 100, they’ll have benefited from 80 more years of medical advances.

Part of why I’m excited about this collaboration is that Wheaton is committed to social justice. We are training students in human stem cell research in an atmosphere where we want all demographics to learn these technologies for the health of all people.”

Laura: Is stem cell research controversial? I understand stem cells now can be developed from adult cells instead of embryonic cells.

Robert: “That’s correct, there’s no longer the need to subject women to the hormonal treatments, and the harvesting of eggs. Those important ethical issues that were raised were alleviated many years ago by advances in stem cell technology.”

Laura: Phil, do you feel like you have to educate people on this?

Phil: “Even to other scientists, I have to make sure I clarify that I’m using induced pluripotent stem cells and not cells harvested from embryos. Being careful about educating and having people be more socially aware of the new technologies is important.”

Laura: Tell me more about EverCell Bio.

Phil: “It’s a single-source provider of customized services for the application of pluripotent stem cell technology. Scientists at labs focusing on different diseases want to use iPS cells but may not be trained for it or require specific technology that they do not have internally. That’s where I come in. For example, people who don’t have expertise in stem cells may want us to make an Alzheimer’s model. I can help make patient-specific neurons derived from accessible tissue from Alzheimer’s patients. In general, the help I offer could be logistical, doing the actual lab work to deliver data or cells, or just providing guidance.”

Laura: Who do you work for?

Phil: “My key clients are mostly small, biopharma companies, but I also have clients in large pharma and academia alike. EverCell’s advisors come from both industry and academia.”

Laura: Phil, tell me more about the genesis of your interest in science.

Phil: “I’ve always been interested in questioning things; that’s the nature of my being. Later in life, I found out that my grandpa, Dr. Philip Manolopoulos, was a famous organic chemist who worked at DuPont. He had some major discoveries that we use every day, like reverse osmosis. So, I guess you could say that my interest in science was genetic. In elementary school, I participated in annual science fairs. For two years, I tried the same project: trying to build a hovercraft. I was obsessed with the ‘Back to the Future’ hoverboard and thought it would be really cool. I wouldn’t say those two years were wasted, but I was unsuccessful in creating a hoverboard.”

Laura: What was your experience at Wheaton like as a student?

Phil: “Wheaton is a place where you can make it what you want. I really liked the collaborative environment and the experiential learning opportunities. I was a resident advisor, an admissions intern, a lab technician and a teacher’s assistant. I also worked at the Lyons Den. One fall, I was coordinator of the Sturdy Memorial Hospital program, where students would shadow professionals. I also did a thesis with Professor [emeritus] Edmund Tong. We studied the effects of Viagra on zebrafish. For another summer internship, I worked with Professor Meg Kirkpatrick at manipulating the sex hormones and behavior of rats and mice. Then, on top of that, I shadowed a doctor in Boston and performed an internship at The Groden Center in Providence that assists those affected by autism.”

Laura: Professor Morris, what are your recollections of Phil as a student?

Robert: “I had Phil in my intro bio course. At that point, I had started this crazy idea of turning Hindle Auditorium into a living white blood cell by having all the students build all the parts. I needed a lot of structures to build: from the biggest, which was the nucleus—half the size of the room—down to the smallest, which was just the signaling molecules. It was Phil who chose the signaling molecules. He had done the calculations that if you enlarge the size of the signaling molecules a million times, it was just about the size of a little sprinkle that you put on ice cream. It’s big enough that you can, I’ve discovered because of Phil, put glue on it, then you can attach it to the end of a wire and make a little cloud of these little sprinkle balls, so they float in space. I still have his model on my desk.”

Laura: Phil, do you remember this?

Phil: “I do. The project is imprinted in my memory. I remember how enthusiastic Professor Morris was at the time.Mostly everyone had these large models, spending so much effort physically and logistically putting them up. Mine was so small, everyone was like, ‘Really? You built that little thing and Professor Morris gets all excited? I spent my whole day building giant cell membranes.’”

Robert: “I was excited about those, too.”

Phil: “He absolutely was.”

Robert: “But they didn’t float.”

Laura: Any other special accomplishments at Wheaton?

Phil: “My first publication was at Wheaton, with Professor Tong. We—along with Joe Lee ’08, Kyle Judkins ’08 and other students—published on a new way to perform image analysis. We were able to measure the diameter and width of blood vessels by the blood circulation without dye.”

Robert: “That was one of the first papers out of Wheaton’s ICUC [Imaging Center for Undergraduate Collaboration]. They used image analysis software in a clever way to look at particle tracking that had been normally used in geology for studying river flow. They realized that whether you’re in an airplane looking down on rivers or you’re in a microscope looking down on blood vessels, it’s the same approach to getting information.”

Laura: After Wheaton, you had quite an interesting career trajectory, working in academia and research nonprofits before starting your own company. Any achievement you are particularly proud of?

Phil: “My biggest win was at Children’s Hospital at the Harvard Stem Cell Core Facility. There, I was co-first author on a paper of a new technology for reprogramming adult cells into iPS cells. Before this, the methods used were not amenable to clinical application because they involved retroviruses that could disrupt normal gene function. So, this was the first method that was completely clean and we were able to produce the first clinically relevant human iPS cells. It was using messenger RNA [molecules that transcribe information from DNA to the ribosome, which determines amino acid sequence and therefore a person’s genetic expression], which had been difficult to use, logistically, in the laboratory to get the effect that you want in the cell.”

Laura: Tell me about your new collaboration with Wheaton.

Phil: “There’s a huge need for more researchers in the stem cell field. That’s primarily where my interest in working with Wheaton students came from. I’ve always appreciated Bob’s enthusiasm and Wheaton for what it is. So, for me it just felt like a logical partnership.

“I like bringing my experience back to Wheaton not just to discuss stem cells but also in the context of professional development. When you reach the point in a scientific career of starting your own lab, it’s not easy realizing that you need more than just your scientific skills to succeed, and no one really prepares you for that. You have to hire somebody. You have to determine and stick to your budget. You’ve got to figure out sourcing materials or technology licenses for your research. And then you think, how do I talk to people? How do I relate my ideas? All of these aspects of the job are not really science, if you think about it. But these things are critical, and we could be preparing the students now for these kinds of challenges.”

Robert: “At his 10-year Reunion, Phil told me that he had this idea to collaborate.”

Phil: “Once we chatted, Professor Morris mentioned that he is using live neurons from chicks as part of the curriculum in his fall ‘Neurobiology’ course. I was like, ‘Well, I can make human neurons derived from iPS cells.’”

Robert: “My eyes bugged out; there was drool on my chin. ‘Yes, please,’ I told him. It was a win-win for all of the opportunities that would be created for Wheaton and the students and for Phil and me.

“It would be a great eye-opening experience for them to see what the career possibilities are, and to see that the dream careers really could be reality.”

Laura: How did the course go?

Robert: “It was fantastic for the students. They take ‘Neurobiology’ because they get to harvest neurons themselves and do their own research projects. There were excited responses that I got after lab and after Phil would visit. At least two of them, maybe three, said, ‘Yeah, Dr. Bob, I’m going to add this extra experiment to my project, because I really want to experiment with these human neurons.’”

Phil: “I was happy being able to get the collaboration going so fast and have it work so well. The long-term possibilities are really exciting as well. In the very least it opened up the possibility of having human cells available to students and being able to expand the horizon on what they might be able to do.”

Laura: What do you think it meant for students to interact with Phil, a former student turned successful researcher and entrepreneur?

Robert: “Wheaton’s very good at bringing professionals to campus. But to have an alumnus who has been successful, a president and a founder of a company in 10 years, who has been to Harvard and Novartis, come back to maybe recruit students? That was huge. As the economy changes, Wheaton students are very wisely being realistic about how their degree can benefit them in a job path. It’s meaningful for them to see examples like Phil of an unconventional, yet successful, career path. It resonated especially well with the students because Phil has come from exactly where they are now.”

Can you imagine starting over again, and developing into whatever you want?

Can you imagine starting over again, and developing into whatever you want? President, EverCell Bio, Inc. (2018–present)

President, EverCell Bio, Inc. (2018–present)