Insightful intervention

Matt Talbot ’03 assesses threat of targeted violence to prevent it

Matt Talbot ’03 was at his home in San Antonio last May when the first reports came in about a possible mass shooting in Virginia Beach. Over subsequent hours the horrific yet all-too-familiar details emerged: a disgruntled worker had quit his job and opened fire on his former colleagues, killing 12 of them before police shot him dead, too.

Like everyone else, Talbot was distressed at the loss of life. But unlike many of us, he didn’t assume the incident was random or unavoidable. In fact, soon after the news broke he correctly predicted to his wife that the shooter would wind up having no history of violence or mental illness, and would have gone through stressful life changes while showing an interest in weapons during the years leading up to the attack.

“It’s the same pattern nearly every time,” Talbot says. “Those would have been the clues to say, hello, red flag—it’s time to intervene.”

Identifying those patterns and promoting intervention is what Talbot does as a behavioral threat assessment subject matter expert. In his day job as workplace violence prevention coordinator for the Department of Veterans Affairs in South Texas, as well as at his recently founded firm Triple Threat Assessment and Prevention Consulting, he builds and manages programs that seek out individuals at risk of engaging in targeted violence. It’s a vocation at the intersection of security, mental health and social work.

“We have to be able to find the logic and the rationale in the most illogical and irrational behaviors,” Talbot explains. While events like the Virginia Beach shooting often are called “senseless,” he says “to the person that did it, it made perfect sense.”

At a time when many Americans despair of finding solutions to gun violence, Talbot’s message is in many ways a hopeful one. He says research has been consistent for more than two decades on the red flags for mass shootings. That means leaders of schools, workplaces and other organizations can teach what to look for, while also putting in place programs that ensure troubled individuals get support.

Talbot compares his approach to the difference between holding fire drills and teaching fire prevention: “People will tell me, ‘We don’t get enough active shooter training.’ I go, ‘That may be so, but what have you done for active shooter threat prevention so that an active shooter response may be averted?’ The goal is that law enforcement never has to respond.”

Talbot is very involved in the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals (ATAP), a national group that has grown to roughly 2,500 members. The president of ATAP’s Texas chapter, Nicole Aguais, ranks Talbot among its most effective members in the nation, praising his positive energy and his openness to new approaches.

“Matt is one of the hardest working, full-hearted, always-a-team-player, passionate people I have ever met,” Aguais says. “He is the type of guy you want in your corner because I feel like there’s no case that Matt can’t handle.”

J.T. Mendoza, deputy director of the U.S. Air Force’s Insider Threat Hub, met Talbot when they worked together on a kickoff event to launch San Antonio’s ATAP chapter. Mendoza says Talbot wants to make the community safer “not by ostracizing individuals that need help but by engaging them and ensuring they get the help they need.”

As for Talbot himself, he says he now has an even more personal motivation for his work: the birth of his first child last year. “One day my daughter is going to be in school as a student and I don’t want her to go to school fearful every day,” he says. “I don’t want to be afraid every day—I know I don’t need to be. I don’t want parents to feel that.”

Finding a supportive environment

Talbot’s road to Wheaton was initially a challenging one. He grew up an only child in Natick, Mass., and succeeded in high school, serving as class president and graduation speaker. But six weeks into his freshman year at Skidmore College, he dropped out, suffering from what he now describes as “debilitating anxiety.”

After taking a year off to get his bearings, Talbot enrolled at Wheaton, which combined the liberal arts environment he wanted with a location close enough to home to commute. His confidence grew and, at the end of his first year, he decided to move to campus. A group of women in his dorm, Meadows, took him under their wing, and they remain among his most cherished friends today.

Talbot also was drawn to the college’s music scene, performing at The Loft and the Lyons Den, experiences that he credits with providing him the self-assurance to now present his work at national conferences and seminars.

“Wheaton gave me back the confidence that I could succeed again, that I could complete something, that I could start something and I could finish it, that even though it didn’t start out the way I wanted to, things could work out,” he says.

In the spring of 2002, he took a course that wound up putting him on his present path: Professor of Sociology Javier Trevino’s class on organized crime, which sparked Talbot’s interest in the world of the socially deviant and emotionally troubled. From there he enrolled in any course that would teach him more about criminality and the dark side of psychology, graduating with a degree in sociology.

After Wheaton, Talbot decided to pursue a master’s degree in clinical social work, which led to an internship and eventually a full-time job in the Massachusetts Department of Corrections. Being a mental health clinician in a prison, he says, was a bracing and frequently disturbing experience that affected him profoundly. He was forced to look at violent offenders as individuals defined by more than just a horrifying act, to see what had motivated them to commit their crimes.

“It was looking past the gang tattoos, looking past the rap sheet of why they’re incarcerated,” Talbot recalls. “It was understanding the circumstances that led the person to the road where they felt they needed to use this behavior to resolve whatever sense of desperation and frustration they were in. That’s exactly what I do now.”

Gaining experience and putting it into practice

Talbot moved to Texas in 2010, joining the South Texas Veterans Health Care System as an emergency room clinical social worker. Because of his experience in the prison system in Massachusetts, he was quickly asked to join a committee tasked with addressing workplace violence and other disruptive behavior.

While Talbot strongly supported the committee’s mission, he found its approach to be unfocused. He spent the next few years learning as much as he could about building successful programs to prevent workplace violence and conducting workplace threat assessments, becoming an expert on the subject.

Tammy Marquez de la Plata, an ER nurse, was among those recruited to the committee by Talbot. “Matt stressed the importance of a preventative, systematic and sustainable approach as opposed to a reactive, knee-jerk reaction, which is common after a violent incident occurs,” she says. She cites internal data showing that reports of concerning behavior by hospital staff have roughly tripled over the past three years, indicating that staff members are effectively adopting the ‘see something, say something’ culture.

“Matt is an integral part of helping to keep our staff, providers, patients and guests of the hospital safe, and I know unquestionably that he inspires all of us on the committee with his enthusiasm for helping to prevent workplace violence,” de la Plata says. “He truly embodies what it means to be passionate about one’s job.”

Talbot’s increasing expertise, and the growing demand for his services, have given him a full plate. Since joining ATAP in 2016, he has won the Texas chapter President’s Award for his work setting up its San Antonio branch. He also is part of the Southwest Texas Fusion Center Public Safety Threat Advisory Group, which meets monthly at San Antonio Police Department headquarters, and this fall he is helping to start a program at local school districts that will train parents to look for warning signs in their own children.

“If we know that we’re concerned about their student, we’re going to ask the student 10 questions, and then we’re going to call the parent and ask them 10 questions,” he says. “Why can’t we teach the parents those 20 questions so they can do this at home? That’s prevention. Because they’re going to see it first.”

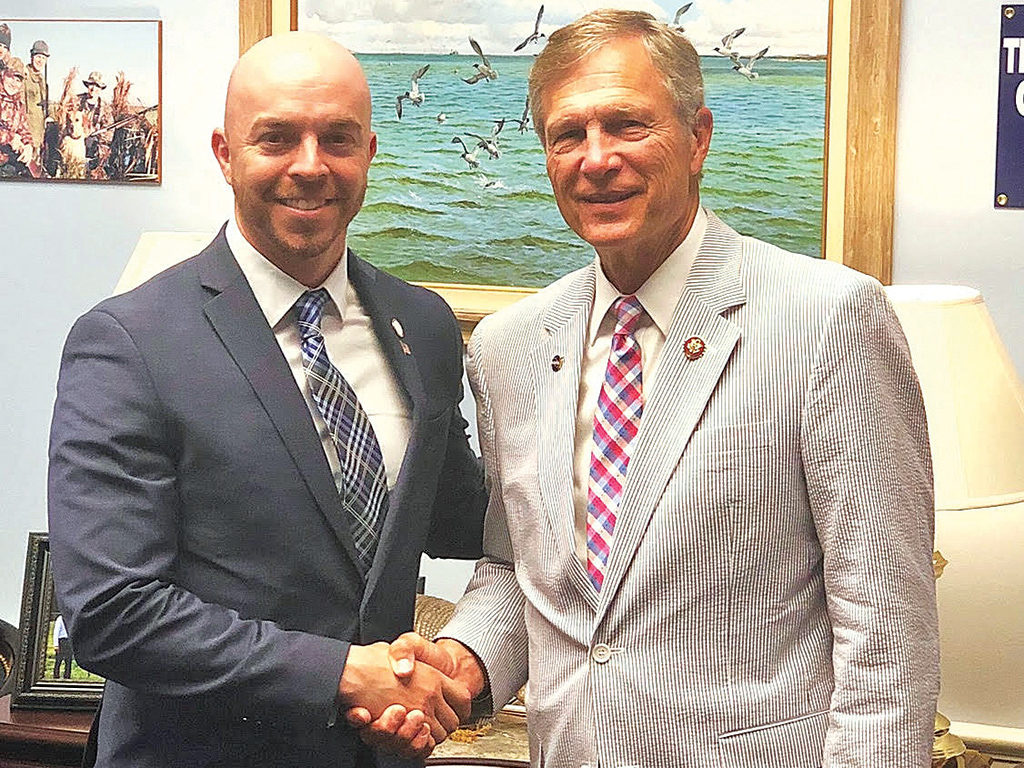

Talbot is hoping lawmakers will take action, too. During the summer he traveled to Washington as part of an ATAP group that visited Capitol Hill to lobby legislative staffers in support of the bipartisan Threat Assessment, Prevention, and Safety (TAPS) Act, sponsored by Texas Congressman Brian Babin. The measure would create a national strategy for implementing threat assessment tools and provide resources for communities to engage in the effort.

“Where we are with violence prevention is where we were with suicide prevention 30 years ago, in terms of implementation and our awareness and appreciation for its importance,” Talbot says. “There’s so much work we need to do.”