The Maimu Seepere Yllo Prize in Women’s and Gender Studies prize was established by Kersti Yllo, Professor of Sociology and Women’s Studies from 1981 to 2016. It is awarded in honor of her mother Maimu Seepere Yllo, who was a political refugee from Estonia, a scientist and a life-long feminist. It is given annually to a senior who has done outstanding academic work and activism focused on women and gender equality.

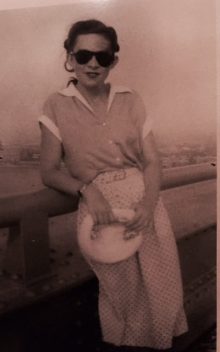

Hamburg, Germany, 1949

Maimu Seepere Yllo was born on September 13, 1921 in Tallinn, Estonia during a period when the country was a free and independent democracy. Maimu was a free and independent girl who excelled at academics, especially science. As a teenager, living on the island of Saaremaa, she dated a number of boys but always made sure to pay her own way with money she earned by tutoring. Maimu was one of very few women accepted at the Tallinn Technical University. At her first chemistry lecture it became clear that she was not fully welcomed when the professor took a look at the two women (among 60 men) and announced “women at the University are like pigs at a banquet” – in the wrong place! The other woman dropped out while Maimu vowed to finish at the top of the class – which she did.

Estonia’s independence period was short lived and with World War II came German and Soviet occupations. Maimu got word from her family that they were planning to escape before the Russians sealed the borders, and she rushed home to the island from the University. She had a few hours to pack before she and her sister and parents headed for the port. They managed to get onto a German troop transport ship with hundreds of other refugees and made a dangerous passage down the Baltic Sea with ships around them being bombed.

The family arrived in northeastern Germany and began a difficult 150 mile trip on foot with the goal of reaching the British occupied zone in western Germany before the war ended. The family had agreed that if they were captured by the Soviets they would consume the cyanide that Maimu had sneaked out of her chemistry lab. Fortunately, despite several close calls, they evaded capture by the Russians. Their travels were made especially difficult because Maimu’s father was disabled by complications from the influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1918. Because he could not walk, Maimu and her younger sister Lia pushed their father and their few belongings in a wooden cart. As hundreds of thousands of refugees fled across Europe, Maimu’s mother Elsa led a small band of Estonians traveling by night and sleeping in barns and ditches by day. Finally, they made it to the British zone.

In Hamburg, Maimu was assigned to a displaced persons camp which had just been vacated as a prisoner of war site. Conditions were poor but safe. The camp was near the University of Hamburg, which had been spared the destruction of much of the city. Since the University had lost most of its student body the British government gave scholarships to some refugees to attend. Amazingly, Maimu was able to do graduate work in chemistry as a refugee. She shared a room with three other Estonian women who also studied at the University and the four became an analytical chemist, an anesthesiologist, a dentist, and a psychiatrist.

At the camp Maimu met Walter Yllo, a handsome Estonian who later became her husband. The camp was also home to an Argentinian band trapped in Germany at war’s end. The British government had this band play at weekly dances for the refugees. Maimu and Walter became expert at Latin dances such as the cha-cha and tango. Maimu also became pregnant. She decided that living in a refugee camp and going to graduate school was not the right time to have a child. She sought an abortion which ended badly; fortunately, her roommate, a medical student, found her hemorrhaging and saved her. Throughout her life Maimu was a strong supporter of safe and legal abortion and of the pro-choice movement.

In 1950 the U.S. passed the Displaced Persons Act and Maimu and Walter, along with many thousands of other political refugees, came to America. Maimu was on a ship that made a rough voyage but arrived at dawn into New York Harbor where she saw the Statue of Liberty for the first time. The Lutheran church helped with resettlement and she landed in Seabrook, N.J. to work as a farm laborer. She saved enough money for a nice dress and bus ticket and went to interview for an opening as a chemist at the DuPont Company. When she introduced herself, the receptionist remarked “We were expecting a Mister!” Sorry, said Maimu, who got the job and worked at DuPont for the next 40 years. For two decades Maimu was paid far less than her male colleagues, and was explicitly told that she would not receive promotions because she was a woman. But the women’s movement and threats of class action lawsuits changed all that. Throughout the second half of her career Maimu received significant raises and was promoted to Senior Research Chemist.

Maimu worked for women’s rights as the New Jersey State Division President of the American Association of University Women. AAUW was part of a coalition of organizations fighting to pass the Equal Rights Amendment. As an avid birder, Maimu also became an environmentalist. The failure of the ERA to pass and DuPont’s environmental record were disappointments for her, yet, broader progress for women and expanding environmental consciousness were dramatic and positive changes she celebrated.

Maimu married Walter in 1951 and their daughter Kersti was born two years later. Since Maimu and Walter were both chemists, they were somewhat surprised when their daughter turned out to be a sociologist. They weren’t surprised she turned out to be a feminist.

Recent winners of the M.S.Yllo Prize:

- Lydia DeRidder ’20

- Caroline Dhyrberg ’19

- Samantha Kelly ’19

- Megan Barnes ’18

- Danielle Dickinson ’17

- Stephanie Kaczowski ’16