First sight

Where did your eye go first when you clicked on this article? How about when you view a piece of artwork, or watch a stage performance, or play a song on the piano? What does that say about the thing you are looking at, and what does that say about you?

Xinru Liu ’19 and Dmitri Korin ’20 are interested in these questions—and in helping others on campus find new questions to explore, using one of Wheaton’s newest high-tech tools: a pair of Tobii Pro eye-tracking glasses.

The eyeglasses, purchased for the college through the InterMedia Arts Group Innovation Network (IMAGINE), feature four tiny cameras that track the movement of the pupils while recording what the eye is seeing. That information is downloaded onto a memory card, which can be mapped, organized and analyzed on a computer using Tobii software.

The students were recruited to work with the glasses last year by Professor of Computer Science Mark LeBlanc. They learned how to use the technology (even attending a workshop led by one of the people who developed the glasses), became familiar with the software, and crafted a QuickStart manual to help future users. They also started exploring possible research areas.

“It’s pretty easy to see the potential within the computer science, psychology and biology departments, because the glasses relate to brain function and eye movement. But we wanted to prove that the technology can be related to all fields and that everyone can use it,” said Korin, a computer science and mathematics major.

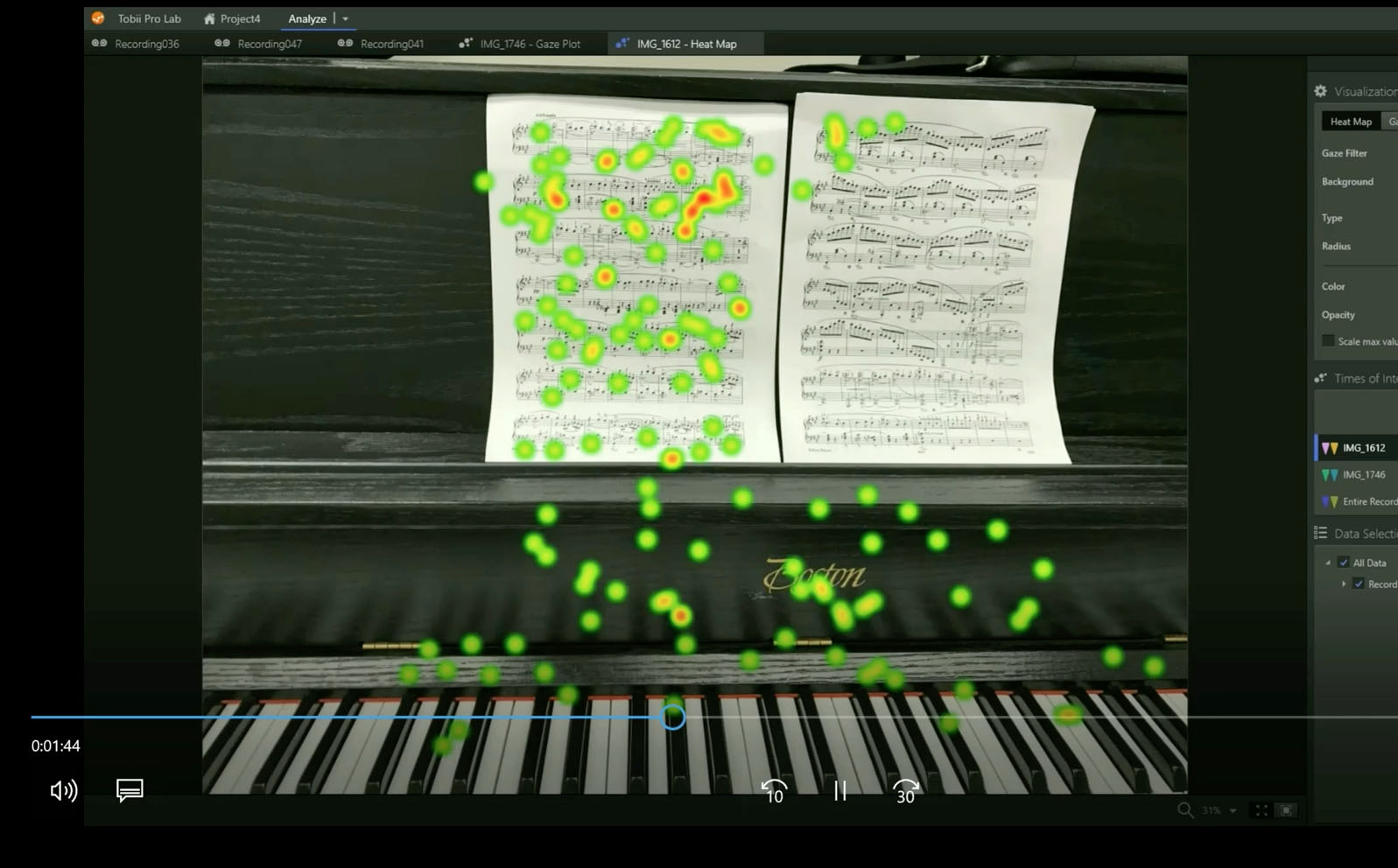

They began by wearing the glasses while looking at different paintings, creating heat maps that revealed the path of the gaze and how long the eye focused on different parts of the canvas. The resulting graphic showed a red area indicating where the gaze lingered longer and green where a gaze was fleeting.

“We looked at a painting down the hall and found that our two heat maps were quite similar, which implied that a heat map might be similar between different users but could differ based on the painting itself,” Korin said.

Though the study was limited and did not have any conclusive findings, Korin said the experiment showed the glasses’ potential in helping to quantify the quality of a painting.

“So if you ask someone first to rate the painting on a scale of 1 to 10, and then have them look at the painting with the glasses, you can see if there’s a correlation between a person’s heat map and how much they like a painting,” Korin said.

They also used the eye-tracking glasses with music. Liu, a computer science and mathematics major who is minoring in music, has played piano for 15 years. She wore the glasses while playing a Chopin piece she had never played before.

“So for the top three lines using a very slow tempo, my eyes stayed on the music sheet longer, and on the bottom where it’s a faster tempo, my eye jumped up and down from the music sheet to the keyboard more frequently,” Liu said. “Now I want to find the difference between the beginner and the experienced pianist playing a piece of music for the first time.”

This data could have educational applications, Liu said, helping music students develop better techniques based on how experienced musicians perform.

“Piano teachers, if they use these eyeglasses, could have a more comprehensive understanding of the student’s performance of a new piece, and the student could figure out where they make mistakes,” she said.

Korin has also experimented with using the glasses to track how a person views a website—an area he’d like to explore further as it relates to web design and his interests in computer science. But he and Liu also are eager to hand off the glasses to others, to pursue a wide range of studies.

“The goal is to start making the campus aware of what the glasses are and how they can be used, and for students to become experts in this domain,” Korin said.

There are obvious academic and career benefits to mastering cutting-edge technologies, but there is also value in the sometimes difficult process of learning to use these tools, Liu said.

“I think there is a big difference between something you learn from class and something you learn by yourself,” she said. “There’s no one telling you how to do it. If you find a problem, you need to solve it by yourself. You improve your ability to learn.”

LeBlanc also sees value in the trial-and-error nature of the Tobii Pro project.

“To be successfully transformative, Wheaton must redefine how we prepare our students for ‘after Wheaton.’ Students must be able to answer the questions: ‘What have you built recently?’, ‘Why would I hire you?’ and, importantly—and this is a strength of the IMAGINE grant in particular and making in general—’What is the last thing you did that failed?’,” LeBlanc said. “I wanted Xinru and Dmitri to try and fail and try again. And they succeeded.”