Finding the pulse of protest

I came to Wheaton knowing I wanted to study biology. I’ve always been drawn to the outdoors, and I had this vision of working in environmental conservation, helping people adapt to climate change. But during my coursework at Wheaton, something unexpected happened—I fell into a deep exploration of protest music.

Music has always been a part of my life. I started violin in third grade and switched to cello later on, playing in orchestra all through school. When I arrived at Wheaton, I didn’t have a cello for a while, so I wasn’t in the college orchestra, but music never left my life.

At the same time, I have been interested in learning Arabic—mostly because I thought it was a beautiful language, written and spoken. During my first year, I took two semesters of Arabic, and as part of that course, we studied the Arab Spring. Around the same time, I was in a world music course taught by Professor Julie Searles. That overlap—learning about uprisings in the Middle East while exploring music’s global impact—sparked something in me.

As part of the world music course, I took an in-depth look at how music had influenced the Arab Spring that began in 2010. Artists like Ramy Essam, who performed solo in Cairo, Egypt’s Tahrir Square with just a guitar and his voice, rallied massive crowds. Other songs, such as Baraye by Shervin Hajipour, pulled lyrics from tweets and social media posts, transforming digital resistance into real-world solidarity. El General, a Tunisian rapper, also stood out as a major voice of dissent. That project opened the door for me to see how music can be a powerful tool—not just to express emotion, but to unify and mobilize people.

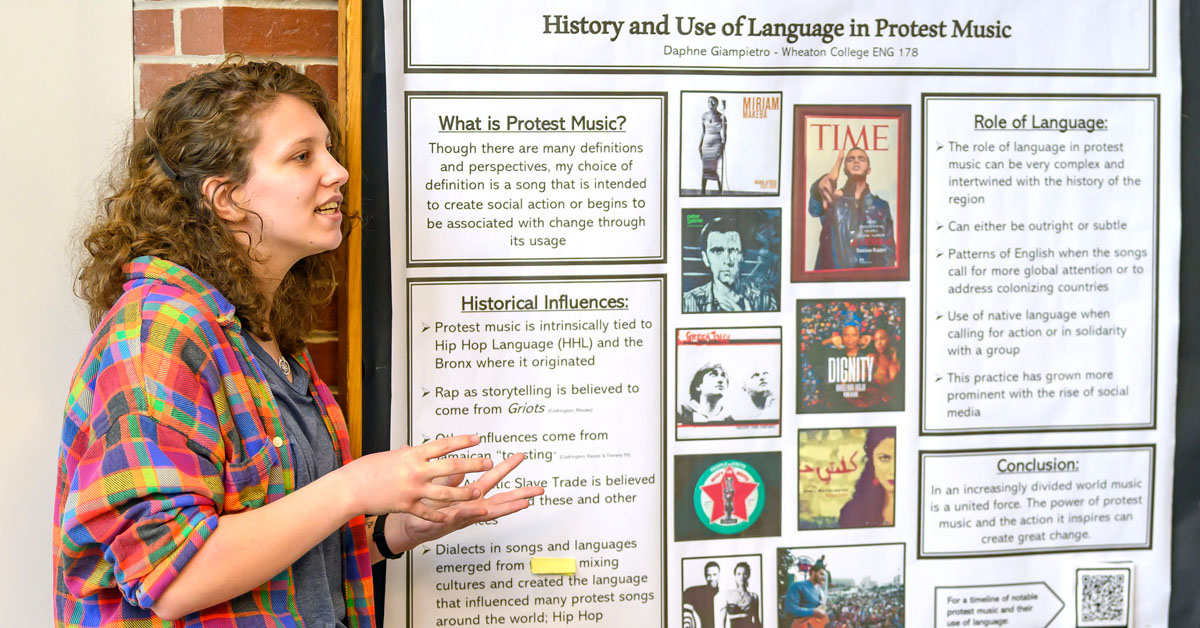

Later, I expanded on that project in a creative writing course called World Englishes, taught by Professor Ruth Foley. That course gave me the space to look at how English and native languages are used in protest songs. It was a challenge—I only analyzed 10 songs in depth, simply because finding reliable translations and context was so difficult. But what I found was fascinating, and I created a timeline mapping the songs, their meaning and the context that inspired each one. In many postcolonial countries, protest songs often use English to speak to global audiences or government powers, while use of the country’s native language shows solidarity with the people and the movement they’re supporting. It’s a strategic and emotional choice—language becomes a bridge.

As someone who listens to mostly indie music and plays classical cello, I found it kind of funny to be digging so deep into punk, rap and other genres to which I don’t typically listen. But I was—and still am—drawn to the raw passion in protest music. There’s something powerful about hearing a song that makes you feel deeply, even if you don’t speak the language. Music has a way of transcending borders, identities and even disciplines.

This is something I love about having studied at Wheaton—the opportunity to take a wide range of classes and discover new topics. Thanks to studying protest music, I got more into sociology and economics because I was fascinated in the psychology of markets and how money affects social behaviors. In fact, I ended up with a minor in political economics.

This work also reflects the kind of scientist I want to be. It’s clear that the researchers who have strong community ties produce better, more impactful work. The ability to connect with people—culturally, emotionally and socially—is just as important as technical expertise. That’s why I value the interdisciplinary experiences I’ve had. They’ve given me a broader understanding of people and culture, how knowledge is shared and movements are built.

—By Daphne Giampietro ’25