Change makers

Back when Dennis M. Hanno was growing up on an isolated farm in upstate New York, he would not have believed it if you’d told him he would one day transform the lives of teenagers in Africa. “I was a curious kid, but not about global travel,” Hanno said. “We never went anywhere.”

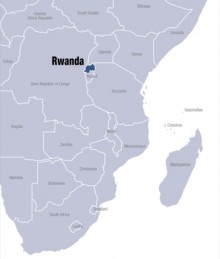

Fast-forward half a century, though, and talk to Jonathan Iyandemye, a 21-year-old Rwandan now attending Harvard: He’ll tell you in no uncertain terms that the efforts of Wheaton’s president have made all the difference in the world to him.

“The impact he’s had is immeasurable,” Iyandemye said recently from his home outside Kigali, Rwanda’s capital. “You can’t talk about it or write about it enough. I feel like I owe who I am to him and a few other people like him who invested in me generously and selflessly, and who believed in me and saw the potential in me.”

“And it’s not just me,” he said. “There are a lot of people out there who have had such a change from Dennis Hanno’s work. I’m just so, so grateful to him.”

Iyandemye is among the thousands of Africans who have learned how to become entrepreneurs and community leaders, thanks to a series of innovative programs created by Hanno over the past 15 years—and taught, in most cases, by undergraduates from Hanno’s former academic homes, University of Massachusetts Amherst and Babson College, and now Wheaton.

Individual comments

- Far reaching goals, President Dennis M. Hanno

- An effective approach, Professor Hyun Sook Kim

- An opportunity to grow, Hannah Gasperoni ’17, biochemistry major

The weeklong seminar now known as the Wheaton Innovation and Leadership Laboratory, or WILL, is a bit like a summer camp for would-be entrepreneurs. Under the guidance of Hanno and his travel companions, roughly 120 Rwandan students spend five intensive days diving into the lessons contained in From Ideas to Action, a 263-page textbook specially created by Hanno and a few collaborators.

“The overarching goal is to work with youths and adults who are interested in thinking about how they can become more entrepreneurial,” Hanno explained. “It doesn’t necessarily mean they have to create a business, but they have to figure out how to take responsibility for solving problems in their own communities and their own lives without expecting someone else to take care of it for them.”

Yet the seminars are about more than just their direct impact on individuals such as Iyandemye—though that impact is hugely important. They also offer a window into how Hanno thinks citizens in the developed world should encourage social change in developing nations, and the value he places on strengthening Wheaton’s identity as a globally engaged liberal arts institution.

“WILL is not a simple service-learning program,” Wheaton Professor of Sociology Hyun Sook Kim explained after returning from a trip to Rwanda with Hanno last August. It “provides the space for participants to think about how they can be intentional in their actions, to see that their education and learning can be applied for self and community development, and also to form new friendships and networks with individuals who come from very different cultural backgrounds.”

“WILL is, in my view, the kind of interdisciplinary, cross-cultural, global educational program that is truly valued at Wheaton,” she added.

For Hanno personally, working in Africa has become a defining part of not only his career in higher education but his life. He has traveled to the continent more than 50 times since his first visit in 2000, and has taken upward of 500 people with him since he first started organizing classes there.

While the Africa programs blossomed during Hanno’s time at Babson, since his arrival at Wheaton he has been working to expand them. In January 2015, he and a group of 14 Wheaton students spent 12 days teaching orphans from the genocide at the Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village in eastern Rwanda and college students at the Catholic University of Rwanda in the southern part of the country. In August 2015, he launched WILL at the Byimana School of Sciences, a boarding school in the country’s south, with the help of 12 students from Wheaton, Babson, Harvard and Barnard. He will head to Ghana again in January 2016 to do similar work, and he plans to return to Rwanda with another group next August.

Creating hope

The young Rwandans who take part in Hanno’s programs have grown up in the shadow of their country’s horrific 1994 genocide, when some 1 million people were slaughtered in the space of roughly 100 days, wiping out entire villages and shattering countless families. Yet the country has made extraordinary progress in the two decades since, and Hanno’s emphasis on entrepreneurialism fits with what many say is helping drive that change.

“Rwanda has come back from the brink of hell and is the most social entrepreneurial country I have ever seen,” the famed humanitarian Dr. Paul Farmer wrote in 2013. Farmer adds, “A pandemic of entrepreneurialism is breaking out there.”

Hanno believes there is a reason that entrepreneurship resonates so strongly in places such as Rwanda. “To me,” he said, “in cultures where there needs to be this growth and opportunity creation, entrepreneurship is the only way to get people that hope they need.”

“If someone isn’t going to give you a job—which is often the case, especially if you’re in a situation like that—entrepreneurship can help you think about how you can create a job for yourself,” he said. “There hasn’t been anyone I’ve ever worked with of the now-thousands who, when pushed to really think about what skills and what values they have in life, couldn’t think of something they could do that would be of value to others.”

John Crawford, a Babson staff member who accompanied Hanno to Rwanda in 2012, said the power of WILL and its predecessor seminars lies in how they broaden horizons. “The program’s biggest impact, I think, is inspiration,” he said. “How many students are inspired to try new things, to improve their lives, to help others, to look beyond their villages and dream up big things?”

The impact of the trips can be transformational for the Americans who go as well. Brooklyn resident Julia Lisi ’18, a religion major, joined Hanno in January 2015 for the first trip to Rwanda he organized at Wheaton. It moved her so much that she decided to return with him for the second trip in August later that year.

“Other universities say go study abroad for yourself; Wheaton says go and do it to help others,” she said.

Lisi said that witnessing the profound impact the seminars had on the students in Rwanda made the trips “among the most meaningful experiences I’ve had in my entire life.” The two visits convinced Lisi that she wants to pursue a career involving the same sort of work, and in the short term she is hoping to secure an internship at Agahozo-Shalom’s headquarters in New York.

Nobody would argue that the trips themselves are easy, however.

In addition to undergoing daylong advance training sessions, those who accompany Hanno have to get a series of immunizations, a prescription for anti-malaria pills, and a yellow fever certification card. Traveling from Boston to Amsterdam to Kigali takes about 24 hours, and Hanno is a stickler for business casual throughout. (“If you were a consultant for a company,” he told the group that went in August, “you would not be in your pajamas on the flight.”) Upon arrival, the food can be mediocre and the heat can be oppressive.

Still, Lisi said Hanno managed to calm her nerves over the prospect of teaching an intensive course to a group of foreigners who were, in some cases, older than her. “I had this weird type of trust in him,” she said. “He’s done this so many times and he specifically told us we’re going to be fine.”

Getting started

Hanno was no world traveler as a youngster on his family’s dairy farm in Glenfield, N.Y. He lived about 50 miles from the Canadian border but rarely crossed it; he and his five siblings didn’t even see other New Yorkers all that often. He didn’t get a passport until he was 37.

He attended college at Notre Dame, then moved back to New York, where he started an accounting practice and a family. Eventually, he decided to go back to school so he could become a professor, which led to a job at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

It was at UMass that the seeds for Hanno’s involvement with Africa were planted. A professor of nursing who offered clinics periodically in Ghana had been told by the leaders of a church there that they needed help with technology, so she asked Hanno to come talk to them.

After a difficult journey, Hanno arrived and met the church’s pastor.

“Are you ready for your speech?” the pastor asked.

“Speech?” Hanno replied.

Unbeknown to him, about 200 village leaders—in tribal dress—were waiting for him to deliver an address. He winged it, and somewhat to his surprise, the reception was positive.

“It struck a chord with them, I think, because it wasn’t the usual, ‘I’m going to come here and save you,’ because I’ve never believed that,” Hanno said. “If you think in a few weeks’ time or a short period of time that you can save the world, then you probably shouldn’t be going because you’re going to do more damage than good.”

Hanno later returned with a group of students and boxes of used desktop computers for the village. The problem: Once Hanno and his students departed, there was no one to teach people in the village how to use the machines.

That’s when the light bulb went off. Hanno realized he needed to teach skills to the Ghanaians while he was there so that they could be self-sufficient once he went back to the United States. That core idea—”teach a man to fish,” as the saying goes—has been central to his work on the continent since.

Soon Hanno was making the trips a regular twice-a-year occurrence, and the lesson plans expanded beyond computer tips to marketing, accounting, finance and other basic business concepts.

Then, in 2006, another light bulb went off. “What we were hoping to do was create a more entrepreneurial culture, to get people to really think about how they could solve problems on their own,” he said. “So the light bulb was, if you’re going to change a culture, you don’t focus on the 30-year-olds; you focus on the 16-year-olds.”

That led to the creation of a business plan competition for Ghanaian high schoolers that by 2014 drew 3,000 students from more than 40 schools. Among Hanno’s favorite success stories was Kobina, a Ghanaian artist who credited the seminar with helping him figure out how to market his works.

Hanno began working in Rwanda in 2007, after he’d left UMass for Babson, when a businessman from the country urged him to offer programs focused on entrepreneurship similar to those in Ghana. But he found that Rwanda had a different feel and different needs than Ghana, particularly in light of the genocide, which led him to create the summer seminar program that is now WILL.

Djibril Rushingabigwi, who won the program’s Rocket Pitch Competition in 2014, said he wasn’t sure at first what to make of the seminar’s focus on subjects such as core values and family ties. But eventually he saw how it all fit together. “There it was,” he recalled realizing, “needs and wants equal business opportunities.”

Teaching, learning and growing

Rwandans call their country the land of “mille collines,” or “a thousand hills.” While its geographic size is similar to that of Maryland, its population is more than twice as large, at more than 12 million. The heavily Catholic nation is still working to heal from the genocide, and those who accompanied Hanno in 2015 were sometimes surprised by what they saw.

Professor Kim recalled seeing scores of farmers working ankle-deep in wet rice paddies.

“I was surprised to see this image of wet rice cultivation, which looked so much like northern Thailand and parts of Indonesia,” she said. “In the morning and early evening, on the way to and from Byimana School of Sciences, where we taught the workshop, we saw farmers walking with many heavy jugs of water and large bundles of long stalks balanced on their heads. We saw Rwandans laboring hard in the fields.”

During the August trip, a typical day at WILL went as follows: a morning lecture by Hanno to the entire group, then small group breakout sessions led by those who came on the trip with Hanno, lunch, then another large lecture followed by another small group session. The week culminated in a business plan competition.

“In one short week, even the shyest students blossomed and found their voice,” Professor Kim said. “The students gained confidence to speak in class, in English, in front of a large audience; brainstormed and pitched their unique ideas for action; and articulated solutions for meeting their community needs.”

Kim saw the trip impact her more than she had expected it would when she first signed up, notably due to the interactive way Hanno led his daily lessons with the Rwandan students. “I have been thinking a lot about pedagogy since the Rwanda trip—in particular about how effective student-centered teaching can be even in cross-cultural contexts, and about what new pedagogies I could develop and experiment with in my own courses at Wheaton,” she said.

As a sociologist, Kim said seeing the impact of the seminar made her reflect on the highly practical approach to encouraging social change that it represents. She is writing an academic reflection on the program’s lessons, which she did not anticipate, and is planning to offer new courses inspired by the experience.

Wheaton Visiting Professor of Chemistry Hilary Gaudet, who also went on the August trip, recalled that the participants “were so driven to make a difference in Rwanda and they were so appreciative of our support. The students all seemed so happy all the time. I am still receiving upbeat notes and emails from them.”

Like Kim, Gaudet said the experience of leading a classroom lesson in a totally different cultural environment inspired her to rethink her methods, which is now impacting how she does her job back at Wheaton. “It really helped me to look at my teaching style,” she said.

And the students who go on the trips take their teaching as seriously as the faculty members do.

“There is a lot of responsibility on the teacher to provide individualized help and understanding for each student,” said Courtney Gilman ’15, a women’s and gender studies major who went on the January trip. “I had to create lesson plans each day in order to keep my students engaged in their lessons and wanting to work hard.”

“On one of these trips, if you’re really invested in being the best teacher that you can be, the students are going to affect you simply in the profoundness of their work and their achievements,” Gilman added. “That certainly happened to me.”

Hanno said he’s noticed a different approach to the seminars from the Wheaton students he is now bringing. “They were challenging the Rwandan students to think in different ways than probably traditional business majors would have done,” he said. “That really helped reinforce to me the value of a liberal arts education, because the Wheaton students were able to approach the problems the students were talking about with a number of different perspectives. It wasn’t just figuring out the financial aspects.”

More trips are just the start of Hanno’s plans for the future in Africa. He recently created a nonprofit called IDEA for Africa—short for “Inspiring Development Through Entrepreneurship and Action”—to tap the hundreds of people who’ve gone on the past trips on an ongoing basis. Wheaton has also formed a partnership to start bringing students from Ghana’s Ashesi University to Norton, Mass.

On a personal level, Hanno said WILL and his previous efforts in Africa have kept him grounded and centered. “Having worked with so many people in so many places, it helps me keep a balanced perspective and understand what really are the important things in life,” he said. “It is family. It is opportunity. It is hope.”

“Africa is not a hobby for Dennis Hanno,” said Crawford, his former Babson colleague. “He is fully committed to the people there.”

No one speaks to that commitment more eloquently than Iyandemye, who said Hanno’s program gave him the direction he needed to escape rural poverty. “After that week I feel like my perspective on the world changed,” he said. “I started feeling like I can do something for myself—I can’t be defined by the past, I can be defined by my present. I can dream bigger.”

After winning his seminar’s business plan competition, Iyandemye returned home to his village and launched his company—teaching basic computer skills in his living room. The business was so successful that he earned enough money to pay his fees and stay in school, and the connections he made through the seminar later proved pivotal in helping him gain admission to Harvard.

The entrepreneurship seminar “opened my eyes to the world and gave me a chance,” Iyandemye said. “It showed me that I actually have value, that I actually can do something, that anything is possible.”

Iyandemye has now come full circle — this year Hanno asked him to join the seminar as one of the teachers. He said he remains immensely grateful for the opportunities Wheaton’s president helped him seize.

“Rwanda is very lucky to have had people like Dennis Hanno, who personally, not just through Babson or Wheaton College, but personally feels so committed to people like Rwandans who have a terrible, horrible history but who are looking to ways they can improve themselves,” Iyandemye said. “It showed me how impactful one person can be by deciding to go somewhere and make a difference.”

Photos by AP/TomGilks