Red eye for black holes

Pulling an all-nighter is a college rite of passage. But how about staying up for three consecutive nights to better understand the inner workings of a black hole?

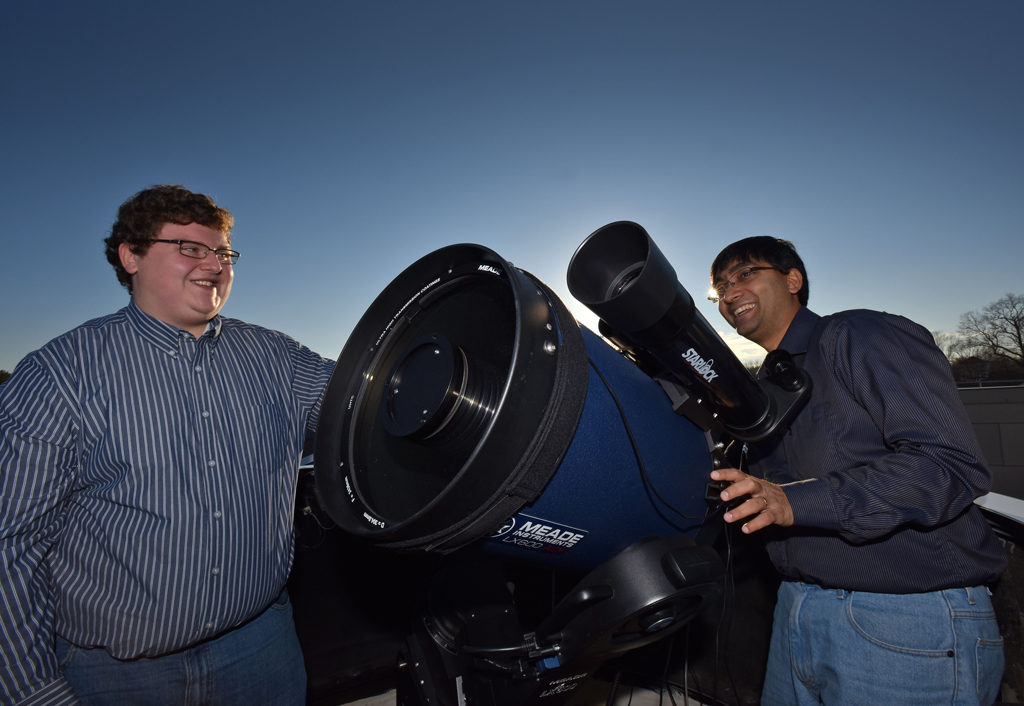

Physics major John Scarpaci ’17, in collaboration with Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy Dipankar Maitra, did just that when offered a rare opportunity to study the eruption of a black hole in real time.

Last June, the black hole binary system V404 Cygni—which had lain dormant since 1989—erupted, and Scarpaci and Maitra had front row seats as the event took place almost directly over Norton. Located 8,000 light years away within the Milky Way, V404 consists of a stellar mass black hole 8-to-15 times greater than the sun, and a companion star a little smaller than the sun.

“This was a totally unanticipated event and made us change all our previous plans for the summer,” said Professor Maitra, who has worked with Scarpaci on various astronomy projects since fall 2013.

When matter spirals into a black hole, the accreted matter gets heated up to tens of millions degrees, and emits light of all wavelengths ranging from visible to infrared through ultraviolet and X-rays. Scarpaci and Maitra set out to study the properties of these different wavelengths to better understand the nature and evolution of the accretion flow near a black hole.

Over the course of three nights, Scarpaci studied V404 Cygni using Wheaton’s newly acquired 12-inch aperture Meade LX600 telescope with an attached CCD camera and filters to study light at specific wavelengths. (This telescope can accurately track the motion of the earth and can follow a celestial object 10 times better than Wheaton’s previous telescopes.)

Scarpaci took the lead, working alone on the third night when Maitra was unavailable to help. Overall, the research team produced hundreds of images and lots of data, which were transferred to a Linux workstation in the astronomy lab for processing and analysis.

“Often the light from the system varied so much that we had to change settings, like exposure times, to adjust for the changed brightness. Thus, in some sense, we could really see the flickering of light originating from very close to a black hole, which is pretty cool,” Maitra said.

Scarpaci said observing the highly energetic and rapidly varying outburst from the black hole was both exciting and awe-inspiring. “I couldn’t stop myself from losing sleep over the analysis of the images. What we saw in our data is not what we would usually expect from a typical jet-dominated outburst.”

Indeed, the results showed that the jet-launching region near the black hole was more compact and energetic than expected.

“This means we may have to go back to our drawing boards and re-evaluate or modify our existing ideas about the process of accretion onto black holes,” Maitra said.

Student-faculty collaboration is all about pushing boundaries on what is commonly understood about particular topics.

Scarpaci’s favorite part of collaborating with Maitra is “having an extra gold mine of knowledge to dredge.”

In Maitra’s view, student-faculty research provides a transformative experience for intellectually curious students by encouraging independent thinking, fostering creativity, and promoting teamwork and collaboration.

“What fascinates me the most is that once the spark is ignited and a student realizes that they are contributing something substantial and new to cutting-edge research, they take the project much further themselves,” Maitra said.

Also, student participation frees him up to think more about the implications of research findings and to see where results fit, or do not fit, in the bigger picture, he said.

Maitra describes Scarpaci as enthusiastic and hard working, and notes his motivation to solve challenging problems. “As a budding researcher, I’ve been happy how aptly he negotiates the learning curve. He can solve a problem if he sets his mind to it,” he said.

Scarpaci’s interest in astronomy began in high school through physics classes and his participation in WiSE (a Workshop in Space exploration)—a three-week workshop. During his time at Wheaton, Scarpaci’s knowledge of astronomy has expanded, with new understanding of fields including observational astronomy and X-ray astronomy.

Scarpaci said he is interested in black holes because they strain our understanding of science. “Here be dragons; here is where the worlds of quantum and general relativity collide. And we do not yet know which is the prevailing theory,” he said.

Scarpaci hopes to eventually obtain a master’s degree in astronomy or astrophysics after he graduates from Wheaton.