Selma’s Manuscript

Selma’s Manuscript

Translated by Tessa C. Lee, Ph.D.

and Shawn Peaslee ’12.

A child Holocaust survivor found a manuscript in the remaining estate of his deceased sister, also a Holocaust survivor. As it turned out, the manuscript is one of the rare diaries written in the Theresienstadt (Terezin) concentration camp during the years 1941-1943 by an inmate named Selma. Little is known about Selma and whether or not she survived. The German department was asked to translate the manuscript and we were honored to do so.

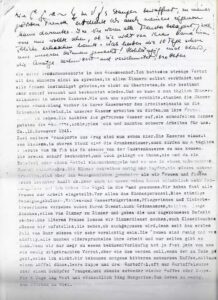

Page 1

Armed with prison bars… To my greatest joy I also discovered my own husband among them. In a second all of the windows were occupied. Every one of us wanted to see, whether they could snatch a glimpse of her husband. What had become of our husbands in 10 days! Hollow-eyed and pale, their suits crumpled and dirty, they trotted in the camp courtyard under gendarme escort. In all of the rooms, I had announced that there was a strict ban against speaking with the men and urgently requested all women not to violate it, since it was certain we would be very keenly guarded and observed. And so now daily, scores of men came into our barracks. As it was recounted later, the men had stood for hours in their barracks in front of the work detail begging for permission to work in our barracks so that they might finally see their wives. They hacked open the frozen water, shoveled snow, cleaned the toilets, hauled wood and performed difficult work for us.

Tuesday, November 18, 1941

Two additional transports from Prague are now also here. The internment camp is abound with children. On the top floor are the sick bays. Four doctors may also come to us from the Sudeten barracks daily from 8 a.m. until 6 p.m. in the evening. They are strictly monitored, but now and then they succeed in smuggling in a little letter or a note and slip it to us in an unobserved moment. The men write boldly and bravely; they must work hard, but they are more accustomed to internment camp life than we women and it is easier for them to put up with it. But our lives also become more orderly. Lene and I have taken the lead. We have divided almost all the women for work. First of all, the kitchen personnel, a constant cleaning unit, coal and water carriers, nurses and child caregivers are already in full service. Also orderlies, mostly young girls, hurry from room to room to forward the orders that have come in for us. We let the older women perform room service. We must also post a toilet watch to see to it that water is constantly flushed down. Ever since the first case of dysentery, we must be very careful. The women are quiet and sensible, everyone performs their work without much ado and only rarely is there a quarrel. If only we received more to eat! For now, almost every one of us has brought with them a little supply, but how it should turn when it gets to the end, I don’t know. In the mornings we get bitter black coffee, at midday a spoon of thin, watery soup and three potatoes, often only potato soup or a ladle of pearl barley, and evenings either coffee or soup again. For 4 days 2 pounds of bread and weekly 1 oz of margarine. Too little to live on, too much to die from.

Page 2

November 30, 1941

I seldom come to writing in my notes. There are now already 3,000 women and children in the barracks, almost a small village, and slowly the organization is too much for me to handle. I was always a private woman and although I have led a large household, I have no actual experience with such mass supplies. It’s true that members of the Jewish Council from Prague arrived here, who were immediately appointed as the council of elders and live in a third building, the Magdeburg barracks, but they are allowed, like Lene and I, on the street only with a passage permit, and these are seldom granted. When we walk over to meetings or pick up provisions, we must walk quickly in the middle of the street. We may not use the sidewalk nor look at the houses inhabited by Aryans. My friend Toni is a coal carrier, Grete Fassel is a nurse, and Lene and I perform day and night shifts in the chancellery, since most often the orders from the Germans arrive in the middle of the night as if they dread the day light. Lene has taken over the field service. She achieves a lot in Magdeburg (barracks) and when she comes back with her high boots and pants, with cheeks reddened by coldness, from a successful run from Magdeburg, I never tire of looking at her beautiful appearance and her starry eyes. On the other hand, I worry about our Toni, who is usually very lively. She is pale and talks little, for her a very worrying sign, and this morning she had a dizzy spell. She suffers because of the separation from her husband; they married just before their transportation to the camp and it is difficult for her to get used to the community life here. I numb myself with work. The day becomes too short for me, in order not to have to think about what is happening to my old mother, whom I have left back in Vienna, and to all of my relatives. My husband, the eternal optimist, always lifts me up with his little letters. I admire him, how he, who is a man of the world and never good for manual labor, at his age (he is 55 years old, 20 years older than I), endures this life and confidently looks into the future. “Selma, for God’s sake, quickly give me an official note. The Camp Commandant has seen me with my husband in the hallway, and he has caught Dr. König when he gave his wife a farewell kiss.” Petrified in terror, Grete Fassel plunged into the chancellery; no sooner that I quickly shove the order of the day into her hand, when the door tears open and SS Staff Sergeant Bergl rushes in. I see the wife of Dr. König standing behind him, deadly pale; a woman from Brno (formerly Brünn) and mother of 2 children; “Where is the second sod, who was just with a man?” he screams at me. „Camp Commandant, Sir, if you mean this one there, I gave her the order to tell the latrine cleaners that the first floor toilet is clogged,” I quickly think and lie. The Germans allow us Jews only one type of work and that is cleaning filth, furthermore they have a tremendous fear of epidemics and contagiousness,

Page 3

and I can appease him only by referring to this type of work. „The woman outside will be thrown in detention; I will examine the other matter. If you are not able to keep your hussies in better check, I will also imprison you.” With that he disappeared, saber rattling. A view through the window shows us that he has Fassel as well as Dr. König led away. A gendarme leads Mrs. König into one of the cells next to the guardroom. News of the incident spreads like wildfire in the internment camp. I calm Grete, who, stunned, cries quietly. I take her off duty and turn her over to Toni, who brings her to our room. The orders of the next day state that Fassel and Dr. König were punished with 25 canings because of their interruption of the work. The latter, Dr. König, was also sentenced to imprisonment. As we were told afterward, the strokes were administered with iron bars on the bare back. After the tenth, the punished fell unconscious, but they were still further beaten until the prescribed number was reached. One month later Fassel could still not walk alone. Dr. König died after three days in prison. His corpse was immediately laid in a coffin and immediately boarded up, so that no one caught sight of how mangled he was.